Banking without liabilities

Reconstructing credit in a trustless world

In August, a previously unknown vulnerability in the code of decentralized finance app Poly Network was found and exploited to allow the transfer of crypto tokens worth some $610 million in a dramatic heist. The incident is being read as a technical matter: simply a bug in the code, a security vulnerability arising from a programming oversight, which suggests responding with security improvements.

But the Poly heist can instead be understood as arising more fundamentally from Poly Network's financial design, and only incidentally exploiting a security oversight. In this understanding, the project is trying to solve a modern version of a very old banking problem—linking payment communities—and its limitations are inherent to the technology.

Poly Network links payment communities

Poly Network creates links between different blockchains. Because each blockchain is a distinct ledger, a given token exists only in a single blockchain. The stablecoin USDC, for example, exists on the Ethereum blockchain and has no meaning on other ledgers. This is an inconvenience for an owner of USDC who wishes to transact on another blockchain.

This situation has an analogy in banking: two customers of the same bank can readily pay one another, by marking up the deposits of the seller and marking down the deposits of the buyer. But the customers of two different banks face just the same inconvenience as transactors on two different blockchains. The term payment community, meaning a group of people who routinely pay one another and who typically do so by transfer of a specific instrument, covers both situations. Each blockchain, with its native token, constitutes a payment community; so do the depositors of a specific bank, using the bank's liabilities.

Poly Network's service tries to make a larger payment community out of the smaller ones, addressing the inconvenience of multiple ledgers by linking transactions across blockchains. A user who owns BUSD on the Binance smart chain, for example, can place it with Poly Network, obtaining USDC on the Ethereum blockchain in return. Poly executes this deal using unattended smart contracts using its own Poly chain, linking the transactions on the other two.

Poly Network's proposition, in the end, is to reduce the inconvenience of non-overlapping payment areas. For this offer to be compelling, Poly must be able to quickly and cheaply transact when its customers wish to do so: if exchange is slow, or expensive, then Poly is not doing much to reduce the inconvenience. The service is thus principally one of liquidity provision.

Ways to link payment communities

Poly Network's approach is logical given the blockchain technology within which it is working. From a financial point of view, however, it is quite capital intensive. The fact that Mr. White Hat was able to take $610 million from Poly's reserves highlights the security implications of such a concentration of funds. But even with perfect security, providing liquidity by keeping on hand a giant store of idle funds entails a big opportunity cost. Why is Poly doing it this way?

We can think of Poly Network as implementing a private settlement account to link payment communities that use the same standard of value, but with different mediums of exchange. This is analogous to the twelve geographical branches of the United States Federal Reserve. Within the US, everyone uses dollars, but payments clear through the branches. Similarly, transactions across the internal borders of the Eurozone clear through the national central banks.

Payments across internal boundaries within these payment communities are typically cleared by accumulating balances in a settlement account, like the Fed's ISA or the Eurozone's TARGET2. These accounts can accommodate large or sudden imbalances of payments by allowing overdrafts: participants are allowed to move back and forth between positive and negative balances. These might become quite large before being settled by the transfer of some other asset, or indeed they might never need to be settled at all if the participants can maintain sufficient mutual trust in some other way.

Poly Network is, more or less, in the position of the settlement account. But within each blockchain-based payment community, Poly transacts in stablecoins, instruments in which it can not hold a negative balance. To avoid the possibility of a zero balance, which would prevent it from transacting further in that instrument, Poly is obliged to hold large positive balances in all tokens. In a settlement account, the surplus agents lend their excess funds to the deficit agents; in Poly's system, all clearing balances must be funded externally.

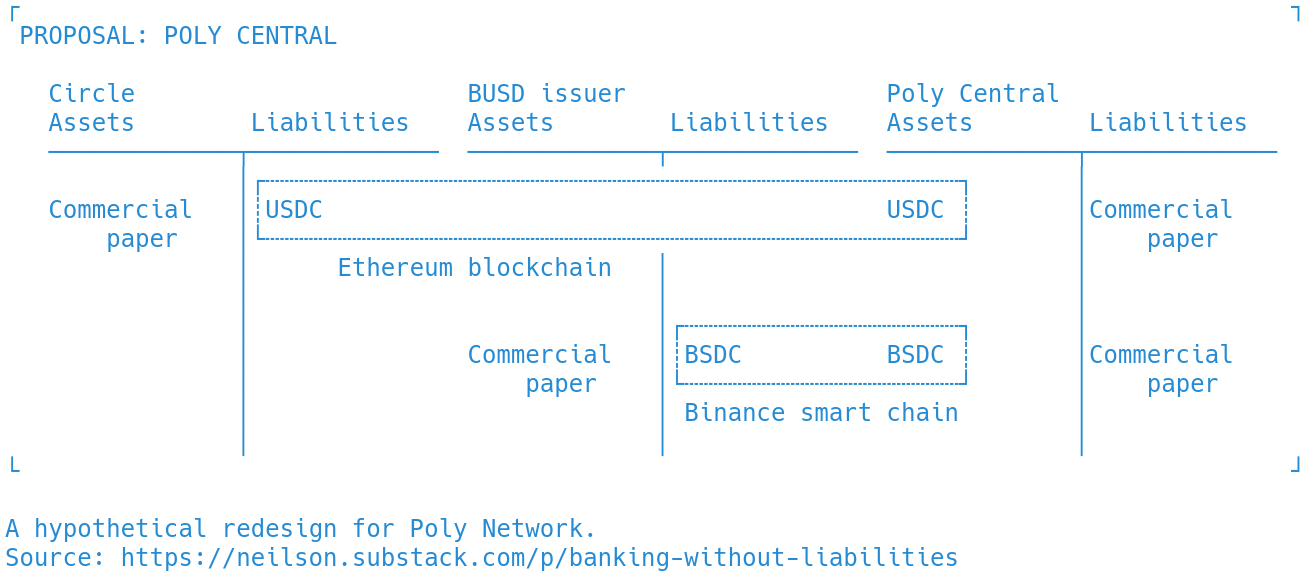

This balance sheet analysis proposes a straightforward solution. Poly Network could fund its clearing balances by selling commercial paper to stablecoin issuers. Under this arrangement, instead of holding large idle balances, it would obtain whatever stablecoin tokens it needed by swapping its own newly issued commercial paper for newly issued stablecoins. Funds deposited at Poly could be used to pay off the commercial paper. (I say commercial paper because that is one of the main assets that stablecoin issuers are already holding, though other instruments might serve just as well.)

Banking without liabilities

This proposal, of course, runs entirely counter to the spirit of DeFi, whose intent is to build a financial system that is systematically and inherently based on trust in code rather than being based on trust in institutions. But as the example of Poly Network shows, this spirit has created a banking system that largely makes do without liabilities: it relies instead on fragile and delicate links between vast idle balances. Poly is lucky to have recovered its funds. DeFi's systemic imbalances mean that these concerns will not go away any time soon.

In the first figure, is the crypto asset user supposed to start with BUSD?