China Evergrande

Ponzi finance 101

China Evergrande, a property developer, has in recent weeks warned that it may soon become unable to make payments on its $89bn in outstanding debts. As news of the company's liquidity difficulties has spread, the price of its bonds has plummeted: on two occasions in recent weeks, trading in its debt securities was halted as investors have sought to reduce their lending to the company.

The company's size, its use of offshore borrowing, and the importance of property development to China's development ambitions all mean that Evergrande's travails may soon become the problems of its lenders, investors and regulators.

Liquidity problems of China Evergrande

China Evergrande, founded in 1996, has grown by riding China's wave of urbanization and property development. Like many property companies, it has along the way become highly indebted. The developer's recent efforts to reduce its indebtedness have been driven in part by the Chinese government's moves to contain property prices. A year ago, property developers were obliged to tighten their borrowing relative to cash, equity and assets—the "three red lines." The liquidity difficulties the company is facing today are the consequence of that policy shift.

Evergrande is trapped in a vicious circle as it tries to cover its debt obligations and payments to suppliers. The company has relied on so-called presales, selling properties to buyers before they are completed. Selling an unfinished property generates cash that Evergrande can use to pay expenses associated with finishing the work. Because it obligates the company to complete the work after the transaction, a presale amounts to selling the property, then borrowing back the cost of the unfinished work.

But with confidence in Evergrande falling, buyers are less willing to extend such credit, and so presales are falling. As the FT reports, this requires the company to borrow elsewhere. But other financing channels are also drying up. Holders of Evergrande's wealth management products, high-yield investments promising low risk or even guaranteed returns, have even staged protests demanding repayment.

The payment demands have become a liquidity spiral, as Evergrande finds that it needs to cut its asking prices to boost property sales and so generate cash. The company has also sought to offload a range of more inventive assets in which it had speculated, including an electric vehicle maker and multiple theme parks.

Ponzi and beyond

While we have China Evergrande under the microscope, it is important to note that its present difficulties have everything to do with liquidity—the company's ability to generate cash. The company's solvency, the relative value of its assets and liabilities, may also be impaired, but the reason that there is the possibility of a consequential default *now* has everything to do with liquidity.

Evergrande's liquidity troubles—selling productive assets to raise cash, recourse to less standard financing channels, inability to borrow—are familiar ones in the world of finance, but there is more to them than merely the fortunes and fate of individual companies. Hyman Minsky, an economist who made his name between the 1950s and his death in the 1990s studying financial crises, observed situations like Evergrande's and built from them a theory of systemic financial instability based on the rising and falling tides of liquidity in the financial system as a whole.

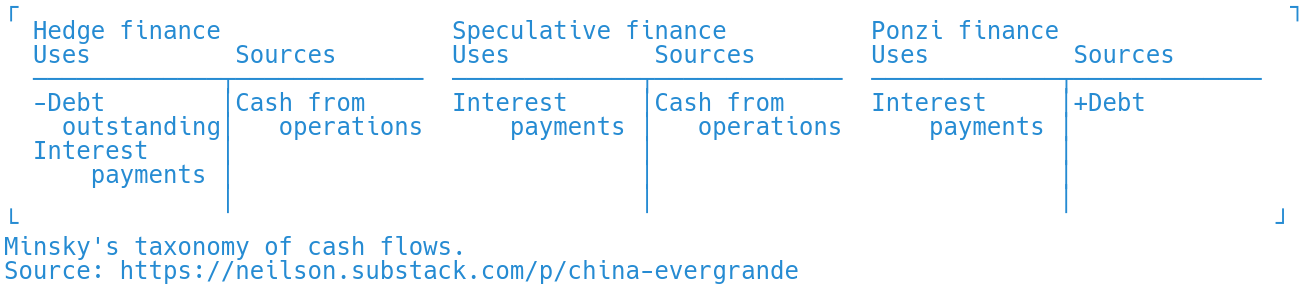

Minsky's well-known taxonomy of firm financing ("hedge, speculative, Ponzi") puts Evergrande's predicament in line with a long line of liquidity crunches. The categorization ranks the stability of financial arrangements starting from the cash flows of a single firm. When a firm achieves "hedge" finance, cash inflows from its operations are enough to allow it to keep up with interest payments on its borrowing, with something left over to pay down the principal. Under "speculative" finance, cash from operations is enough to keep up with interest obligations, but principal has to be rolled over, so the debt load does not fall. Under "Ponzi" finance, the firm has to add to its borrowing just to keep up with servicing its existing debt. A Ponzi firm's debt load is rising. The three categories can be helpfully represented using sources and uses accounting:

One of the reasons Minsky's idea is useful is its flexibility: the "operations" that generate cash inflows could be those of a bank (incoming loan payments), a household (wage or salary payments) or a property developer like Evergrande (sales). Evergrande, we could say, has by now passed through Ponzi finance on its way to something even more unstable: not only has it been adding to its borrowing, it has been selling off the assets by which it might have hoped to one day generate stable cash inflows.

Systemic risk

Another reason that Minsky's analysis is helpful is that it illuminates the path from an isolated scramble for cash like Evergrande's to a systemic liquidity crisis. Evergrande needs cash now to service its liabilities. Those debts are assets to others, so if Evergrande fails to make a payment, that will be a payment not received by its lenders. If that in turn causes the lenders to miss a payment, then a full-on liquidity crisis is underway.

That's always a possibility. But for the moment, China Evergrande is looking mostly like a textbook example of an illiquid firm.

Does Minsky's story neglect purely financial operations, available to any firm, such as for example selling debt high to buy it back low? Or investing debt in derivatives that hedge inflation, for another example?

Isn't irrational, emotional, panic, spreading to otherwise perfectly safe assets the real problem? I.e., prices are arbitrary and funding cost inflation is easily solved by the Fed supplying liquidity from an infinite store?

Or maybe the CCP will try to forcibly put down the Evergrande panic by banning fire sales?