Monetary policy in a disorganized economy

I have struggled to write, faced with the meaninglessness of war. But the purpose of Soon Parted is to use the institutions of money and finance to see what can't be seen in other ways. This is the world we have to live in, for better and for worse, and writing still seems like a worthier choice than silence.

When the facts change, financial relationships change. Some who had expected good times instead fall on hard times, and so payments are missed, and debts must be refinanced or else defaulted upon. The monetary and financial systems are a daily window onto these adjustments, and so onto humankind's changing social circumstances. Much can be learned from patterns of refinance, measured on the balance sheets of central banks and other systemically important financial institutions, and from patterns of interest rates, especially measured in markets for overnight funds.

Two years ago this week, give or take, we were collectively absorbing a set of changed facts, as COVID-19 emerged, touching on every aspect of social and economic life. Today, with the disruptions of the pandemic still quite present, we are collectively absorbing another set of changed facts, the facts of Russia's war on Ukraine. This war is further disrupting an already disrupted global economic system.

A disorganized production system

Much of the economic effects of the pandemic have come in the form of supply-chain disruptions. The abrupt stop–start of global production in March and April 2020, working conditions in spaces of production, transit and shipping, and labor shortages as a result of illness have combined and intersected in complicated ways. This bulletin from the BIS is quite helpful in describing and measuring the issues succinctly and systematically.

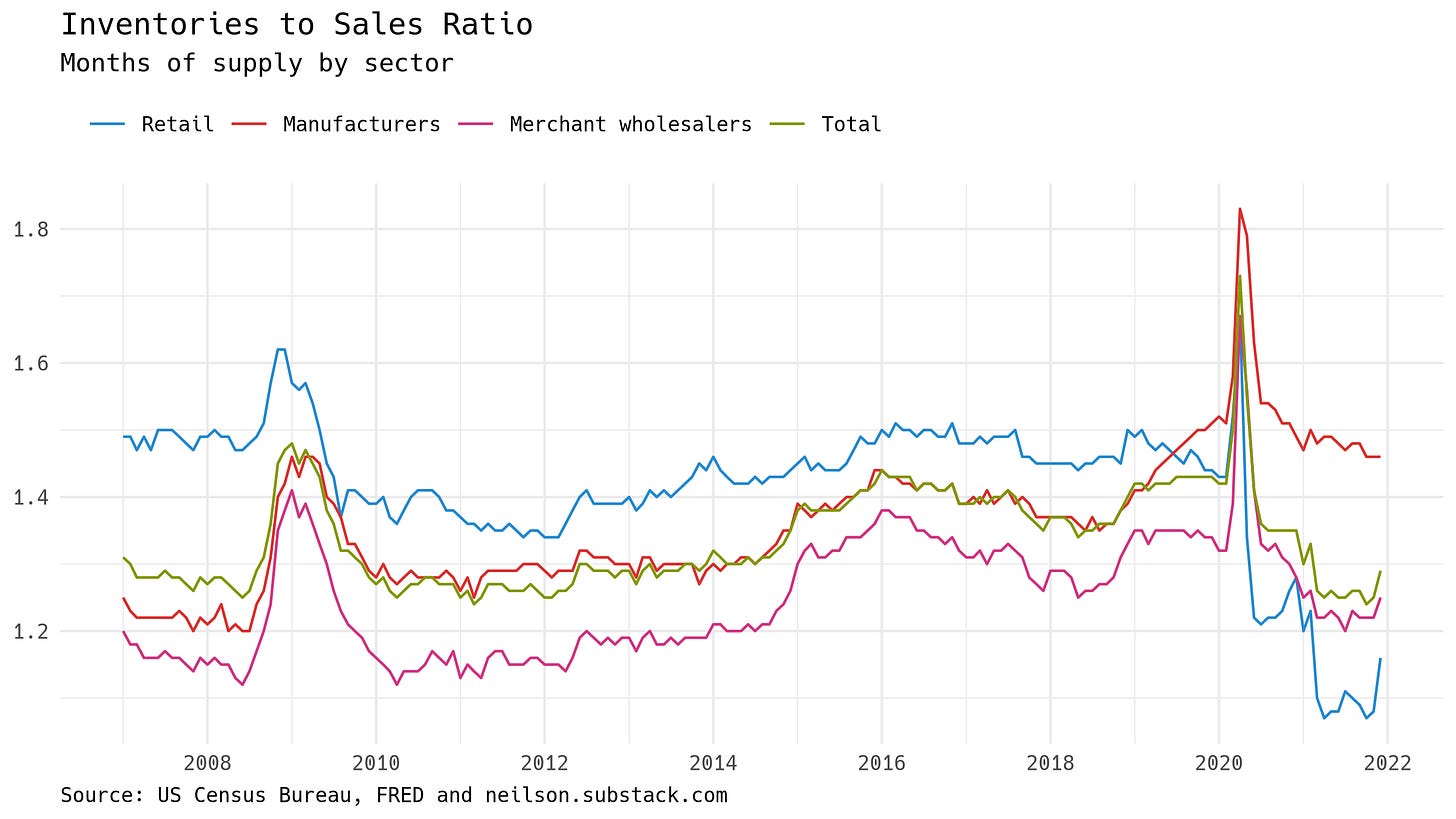

Inventories provide one measure of supply-chain disruptions. The graph below, using US data, shows inventories-to-sales ratios by sector. An initial spike in inventories across all stages of production was followed by de-stocking, all within the early weeks of the pandemic. Since the middle of 2020, levels of inventories for retailers and wholesalers have been low compared to their post-2008 norms, while manufacturers' inventories have been very high.

In other words, the graph shows that upstream blockages are leading to downstream shortages. As the BIS paper shows, this pattern has shown up across geographic regions and industries. Just-in-time manufacturing processes, based on minimal inventories, have proven to be fragile—not only easily broken, but also difficult to repair.

The global production system has thus become disorganized. One of the main symptoms of this disorganization has been inflation, now reaching levels not seen in four decades. The graph below measures monthly US consumer price inflation. The top of each stack shows the headline CPI number, as a percent change over the previous year, 7.5% as of the January 2022 release.

The colored regions show a breakdown of the sources of the price changes. Price rises for nondurables can be most directly attributed to supply-chain issues, but inflation is everywhere, with substantial contributions to headline CPI from each category.

Monetary policy

Today's inflation has little to do with monetary policy. It is about the pandemic, and now the war in Ukraine is likely to cause further price increases, most evidently through the price of oil. Be that as it may, the US Federal Reserve is constrained by its mandate to respond, and the tools that it has to do so are to raise interest rates and to contract its balance sheet. FOMC chair Jay Powell affirmed last week that interest rates are likely to rise at next week's meeting. The course of policy beyond that seems less clear now than two weeks ago.

Here then is the contradiction into which monetary policy will soon have to venture: the Fed will respond to rising prices, with policy that has little connection to the causes of that inflation. Making borrowing more expensive seems unlikely to bring down the cost of commodities, or of durable goods (think vehicles). Interest rates could affect the price of oil or services, but only by reducing global demand, and from the chart above, that reduction would likely have to be quite sharp. Disorganization seems set to continue.