Dollar hegemony in the foreign exchange markets

Quantifying centralization

Theories from international economics often imagine a flat international system: purchasing-power parity, for example, says that exchange rates should adjust to equalize price levels in different places, as though any two countries can be treated as peers in the international sphere. In political-economic terms, however, the system is not at all flat; it is strongly hierarchical, with rich, developed, northern countries exerting disproportionate sway on the fortunes of poor, developing, southern countries.

This hierarchical structure is hard to miss, I think, for those who observe markets daily. But it can be quantified and visualized using data from the triennial survey of the Bank for International Settlements, the central bankers' central bank. This post illustrates dollar hegemony by looking at the structure of global foreign exchange markets.

Market segments

This graph shows the breakdown in average daily turnover in April 2019 (the most recent survey period) according to the segmentation of the global FX market used by the BIS. Perhaps the single most salient fact is the overall scale: daily turnover across all segments of nearly 7 trillion USD. This figure nearly doubled during the 2010s, and more than doubled during the 2000s.

The aggregate measure obscures the differences among the instruments. FX swaps, the largest single market segment, might be best understood as a money-market instrument, lending in one currency against collateral denominated in another; spot foreign exchange, the next largest segment, is a simpler transaction, the sale of funds in one currency for funds in another currency. Outright forwards extend in time like FX swaps, but are in other respects more like spot exchange.

Dollar centrality

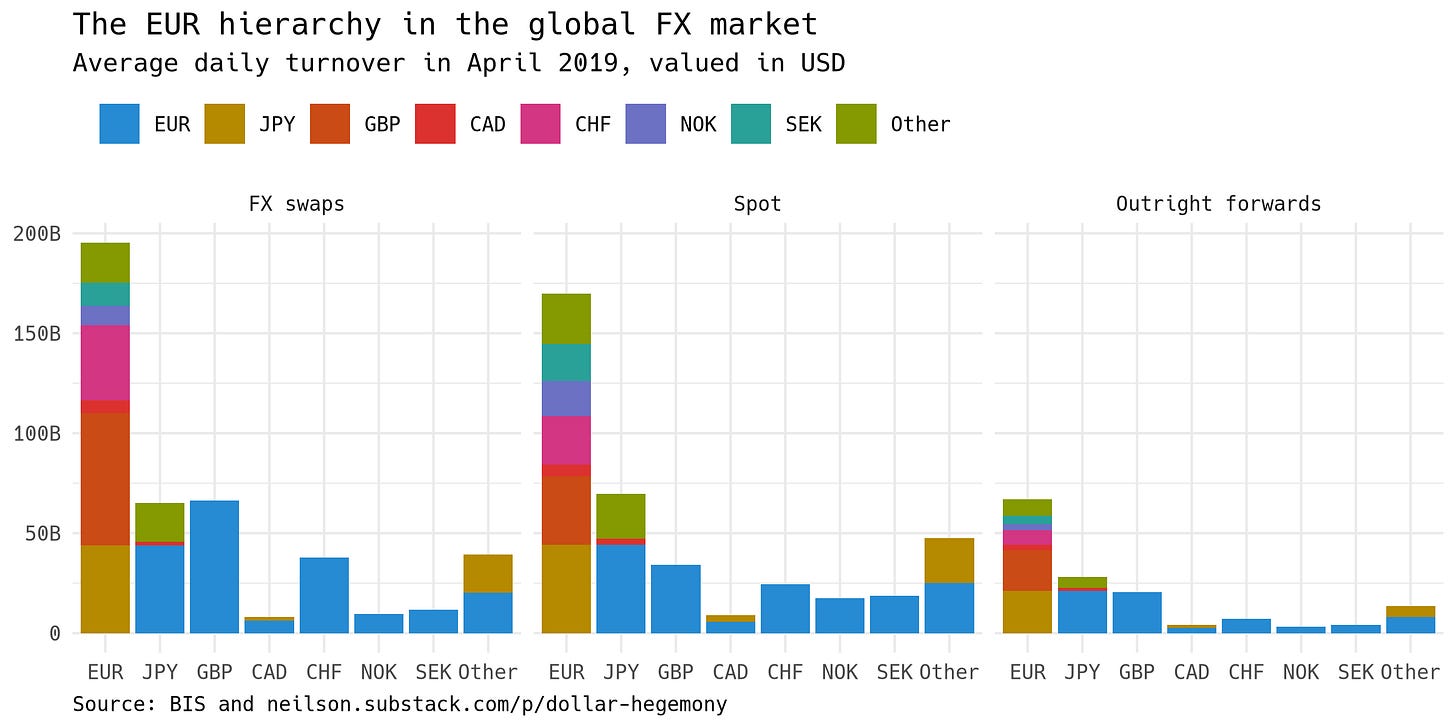

For some questions, these distinctions are certainly important: the various instruments are not all serving the same purpose in the global financial system. But if we look more closely at the currency structure of the various market segments, in broad strokes they tell a single story. This graph shows the currency breakdown of average daily turnover in April 2019 in the markets for FX swaps, spot foreign exchange, and outright forward exchange. I show only the seven currencies with the largest turnover.

Importantly, everything in the BIS FX data is counted twice. A USD–EUR FX swap, for example, is counted once under USD, and again under EUR. (This is visible in the graph, where you can see the first yellowish rectangle above USD is the same size as the first blue rectangle above EUR.)

The implication jumps out: in each market segment, USD is exchanged against a rainbow of other currencies, while every other currency has a big blue box of exchange against USD, and tiny boxes of exchange against other monies. It's not only that USD is more used: dollars are actually doing something different. It is a dollar-centered global system, and other monies are more frequently exchanged against dollars than against one another.

Smaller hubs

One can dig a bit further. This next graph has the same structure as the previous, but I have pulled out all USD transactions, so it is a picture of the global non-dollar foreign exchange market. Note that the scale on the vertical axis is very different: for example, average daily FX swap turnover for EUR, other than USD–EUR, is about $200B, less than 10% of the corresponding measure for USD.

The scale is smaller, but the structure is not dissimilar: EUR dominates the rest of the list and shows sizeable positions with each other currency; these others mostly show a lot of volume against EUR, and little against other currencies. The euro, it seems, serves a similar function to the dollar, but at a different level of the hierarchy. Note the relative size of exchange of euros against British pounds, Swiss francs, Swedish kronor, and Norwegian kroner, all in use in the neighborhood of the eurozone.

Only the Japanese yen shows sizable turnover against currencies other than USD and EUR. The next graph changes scale once again, to about 10% the size of the EUR market, or 1% of the size of the USD market:

We seem the same pattern once again: sizeable FX exchange between yen and the monies of regional neighbors (Australian and New Zealand dollars). The other entries—Canadian dollars, Brazilian reais, South African rand, and Turkish lira likely have to do with trade flows.

Not flat

The foreign exchange market, then, is not flat; across every market segment, it is strongly hierarchical. The US dollar is unquestionably the key global currency: most exchange across the world has dollars on one side, regardless of what currency is on the other side. Farther down, the system is still hierarchical, with the euro and yen playing comparable roles on successively smaller scales.

I have focused here on quantifying and visualizing this dollar hegemony, but the implication for theory is also important: it is theoretically wrong to treat all currencies as though they are peers. The hierarchical structure gives a political-economic shape to global exchange. If it doesn't reflect that fact, then the world of theory has little relationship to the world we actually live in.

Message to teachers: Based on names and email addresses that I recognize, I see that Soon Parted’s readership includes quite a few professors. If you find a way to make these posts useful to you in your teaching, please let me know what you teach and how you use them—I’m very curious. Thanks!

Fantastic post. This is something that I also find highly underappreciated, especially in discussions about the nature and sustainability of USD as a reserve currency and speculations as to the future value of the USD. 96% share among interdealer FX swaps is a pretty resounding statement about what it really means to be a global reserve currency. More than trade invoicing or relative GDP, it's about financial infrastructure/architecture.

Good post. Note that also everything is quoted against usd and bid/offer in fx swap over USD tends to be narrower than most other two currency pairs directly (ie to go from one currency to another ppl might use USD on both sides).

From my own experience, FX swap is used moch more these days now banks are required to monitor LCR on a currency basis, so dominant Eur or JPY banks have to swap more and earlier to maintain their USD LCR.

Last one, with all the excess liquidity banks also try to place with the central banks that give the best return for the lowest credit exposures (CHF, GBP, USD, JPY sometimes) when very long in their own currency. That means more fx swap turnover.