China's digital currency

Smart contracts for monetary policy?

China's new digital currency, called the e-CNY in the People's Bank of China's own recent publications (elsewhere e-yuan, DCEP, digital RMB, etc.), has prompted commentary on its payment innovations, privacy implications, role in international transactions, and potential financial stability implications. There is another angle that deserves attention: digital currency as a transmission vector for monetary policy. Joseph Wang mentions in his book that fine-grained monetary intervention is a key motivation for central bankers (not only in China) to pursue digital currency projects.

One still has to dig a bit for good English-language sources on the e-CNY project, but a July 2021 PBOC working paper offers a helpful official overview. A January 2021 piece by Yaya J. Fanusie and Emily Jin focuses on developing CNAS's liberal critique of China's digital currency, but also offers a comprehensive bibliography. From these sources, it is possible to say quite a bit about what central bankers at the PBOC hope to achieve with the e-CNY.

E-CNY on the PBOC balance sheet

Start with the central bank's balance sheet. The graph below shows the largest components of the Chinese central bank's balance sheet since 2011, with assets to the left and liabilities to the right. (The vertical lines in 2011 and 2017 mark changes in the FX reserve accumulation regime, which I wrote about here and here.) The quantities are in Chinese yuan renminbi, which trades at about 6.5 to one USD at this writing.

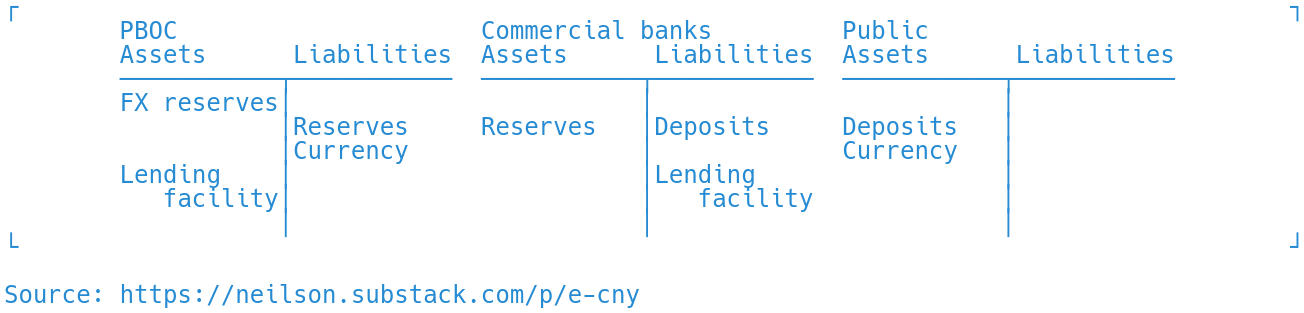

The PBOC has already begun issuing e-CNY, but the quantities are still tiny and they are not reported on the balance sheet. This picture can still be helpful, however, in interpreting what the central bank hopes to achieve with its digital currency design. Note that on the asset side, only the entry for bank lending fluctuates from month to month. On the liability side, there are several fluctuating entries. Because the balance sheet balances (total assets equal total liabilities), all of these fluctuations on the liability side are absorbed by fluctuations in just the bank lending line on the asset side. These T accounts illustrate central bank's financial relationships:

CBDC on the central bank's balance sheet

Where does CBDC fit into these pictures? E-CNY will appear as a liability entry to the central bank, so on the right panel of the graph above. It will substitute, to some extent, for banknotes and reserves. Banknotes' physicality means that they will always be stickier than reserves, which are electronic, so I will focus on the latter.

Similar to Swedish Riksbank's e-krona pilot, the e-CNY uses a two-tier system of financial relationships. The first tier, between the central bank and commercial banks, is based on issuance and redemption of e-CNY in exchange for reserves; the second tier, between banks and the public, is based on e-CNY payments and exchange between deposits and e-CNY. Reserves, deposits, currency and e-CNY are all meant to serve as money, so all of these exchanges are meant normally to occur at par, a constant fixed price of one.

The problem faced by the banks in this two-tier system is to finance an inventory of e-CNY so as to be able to sell them to customers in exchange for deposits. Whenever a bank's customer uses deposits to buy e-CNY, this inventory shrinks, the deposits are destroyed, and the bank's balance sheet contracts. This could increase the fluctuations that the PBOC's balance sheet is already absorbing.

If flows between deposits and e-CNY become large enough to threaten par clearing or bank balance sheet positions, policymakers may feel they need to offer banks a channel for refinance. As the balance-sheet graph above shows, they are already using the bank lending channel to manage the availability of reserves, so it could likely be used to support e-CNY issuance as well. These T accounts illustrate the two possibilities:

In the first strategy, bank balance sheets are allowed to contract, while the central bank's balance sheet holds steady. In the second strategy, central bank balance sheet expansion prevents commercial bank balance sheets from contracting. Note that these T accounts do not have any particular sense of time: it could be that the first strategy is used over the long term, while the second is used in the short term.

Smart contracts and monetary policy transmission

So far so good, but none of this really makes clear what the central bank hopes to gain. Why not just impose tighter regulations on banks and fintech payment providers, get the benefits of electronic payment innovation and call it a day? The answer, as former central banker Yao Qian suggests, lies in the use of the smart contract funtionality built into the e-CNY design. Smart contracts allow conditional logic to be programmed into financial agreements in the payment system itself. The logic is automatically tested and the contract is executed accordingly. One might think of an options contract that is executed automatically if it is in the money at expiry, or an automatic expiration for an equity share order. E-CNY smart contracts expand on this idea by operating in the monetary system itself, and by enabling a more complete set of logical conditions.

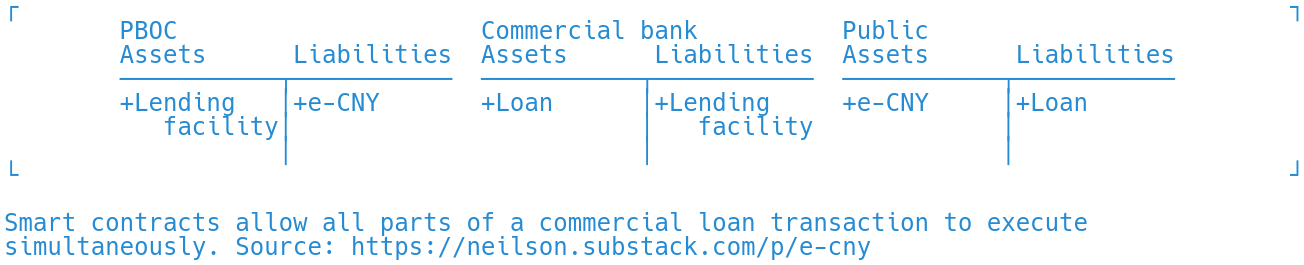

One example from Yao's paper is a time-contingent smart contract that causes e-CNY to be created when a bank closes a commercial loan. Using the central bank's lending facility, for example, a commercial loan could be structured as shown in the T accounts below. When the loan was agreed, the commercial bank could borrow from the lending facility, and the smart contract would trigger the immediate issuance of the e-CNY: transactions that are economically connected could be automatically synchronized. From the central bank's point of view, this has the benefit of reducing the transaction float, the payment initiated but not completed at any given time.

The types of contingency that the PBOC has built into its e-CNY give a sense of the central bank's ambitions for the project. Smart contracts could depend on timing, as in the example above, on characteristics of the counterparties, or on prices or other economic variables. Such an architecture would give the central bank extensive and fine-grained control over transaction flows. For example, a smart contract contingent on a macroeconomic variable could automatically expand or contract credit in response to changing conditions. Rather than having to hold a monetary policy committee meeting to raise or lower a reserve ratio requirement, the central bank could pre-program its response function and have it execute automatically.

Outlook

This ambition is still far from being a reality, and experience will be the only way to judge whether smart contracts mark a decisive new paradigm for central banking. For now, the PBOC is forging ahead with its CBDC project. Other central banks are moving more slowly while watching China's experiment closely. If central banks can really become "not only the decision-maker of money supply but also the designers of algorithms and rules," as Yao suggests, then substantial new thinking on monetary policy will be needed.

Good article, I just want to mention that the link in the third paragraph and at the end of the article called The PBOC standing bid does not go to the page, it is missing a hyphen before the word bid, https://neilson.substack.com/p/pboc-standing bid