The ECB’s liabilities

Zero interest rates come to an end

In mid-September, the ECB recorded a three trillion euro movement out of reserves and into its deposit facility, but unless you make a habit of reading central bank statistical releases, you might have missed it:

Any flow that measures in the trillions is worth some attention, though this one, I think, does not give any particular cause for panic. It is interesting, though, as a side-effect of rising interest rates—or more specifically as the end of one of the vestiges of a decade of zero interest rates.

The ECB as banker’s bank

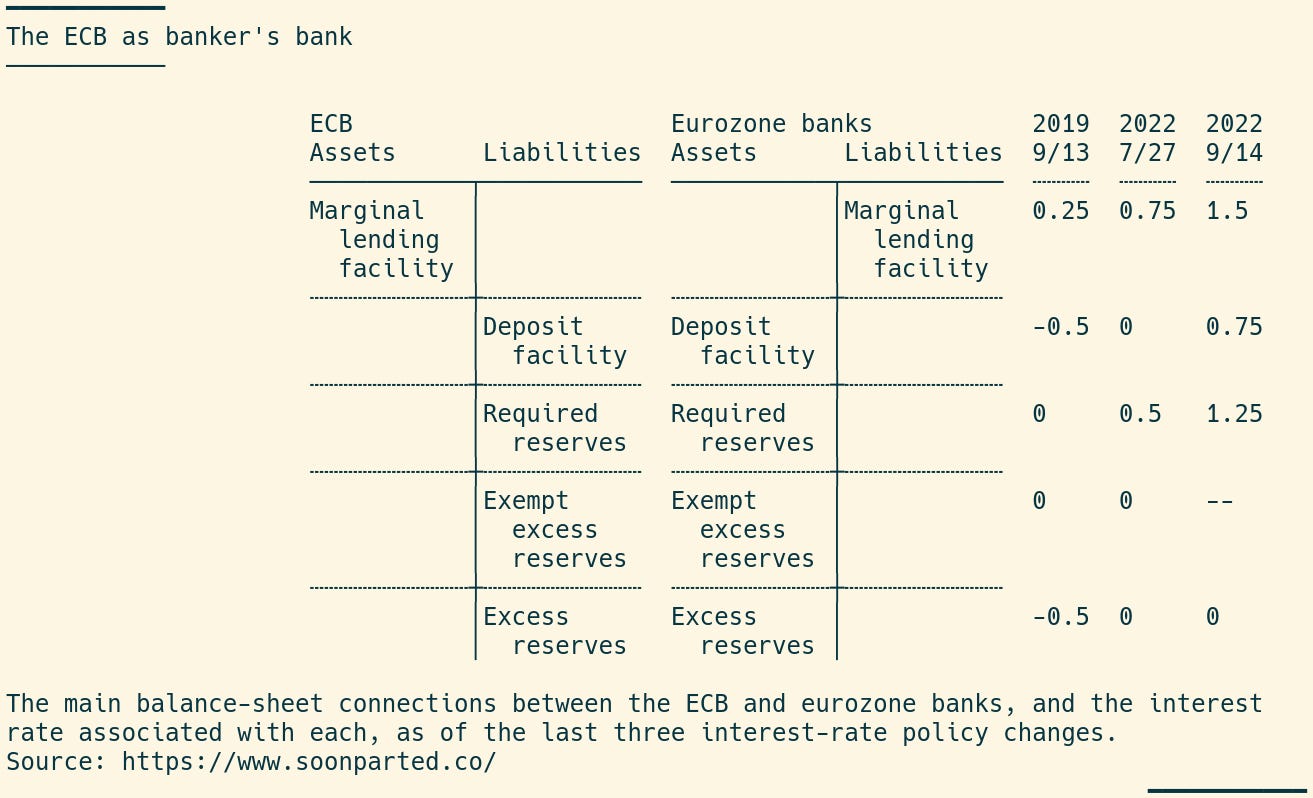

The T accounts below show the main balance-sheet relationships between the ECB and the European banking system. First is the marginal lending facility, included mostly for completeness: it has been used only occasionally, not in great size (reaching a peak of 25 billion euros in 2008), and hardly at all since 2020. Still, the facility’s rate is one of the ECB’s three policy rates. Next is the deposit facility, now the central bank’s largest liability, with its own policy interest rate. And finally three categories of reserves, also a liability to the central bank:

To understand the three-trillion-euro shift from reserves to the deposit facility, we need two further observations. The first is that the ECB has been raising its three policy rates (marginal lending facility, deposit facility, and main refinancing) together, maintaining the spread between them (though at other times, those spreads have been changed). To the right of the T accounts above, I show the interest rate for each balance as of the ECB’s last three rate changes, on September 13, 2019 and July 27 and September 14 of this year.

The second observation is that there is more than one category of reserves. Prior to September, there were three: required, exempt, and excess. Banks are required to hold a certain level of reserves, and the ECB pays the MRO rate (currently 1.25%) on these balances. Reserves above this level are called excess, and on these the ECB pays either the deposit facility rate, or zero, whichever is lower. So when the deposit facility rate was negative (from June 2014 until July 2022), excess reserves incurred an interest charge.

In 2019, however, the ECB lightened this burden by introducing a third category of reserves, which benefited from a floor of zero, and so were exempt from negative rates. So under this “two-tier” system, exempt reserves earned no interest, better than the minus 50 bp on offer at the deposit facility.

Goodbye, ZIRP—or à revoir?

After the July rate increase, excess reserves and the deposit facility both paid zero. And now, following the September increase, excess reserves still pay nothing, but the deposit facility pays three quarters of a percent. The banks duly moved 3 trillion euros and change from their reserve accounts to the deposit facility. At an interest rate of 75bp, this balance will collect some 65 million euros in interest per day.

I would say that this is mostly a curiosity of the monetary plumbing. Not a cause for alarm, but a milestone between the period of low and zero interest rates, now ending, and whatever comes next.