Evergrande's survival constraint

There is a reason that this is happening today

As I write, in the afternoon of Sept. 23 2021 in the US, the world waits to learn the fate of property developer Evergrande. The struggling company is large, it has borrowed lots of money domestically in China and internationally, and it is in some way representative of a larger class of Chinese property developers. What is more, the property sector has been of great importance to China's development ambitions, and perhaps for this reason, financial pressures have long been allowed to simmer there.

We'll know soon enough whether Evergrande's problems will become someone else's problems—lenders, the Chinese government, the PBOC, the financial system as a whole. But for the moment, the Financial Times is saying "Evergrande deadline sends chills through $400bn Asian debt market," and that deadline means we should say something about the survival constraint.

Today's the day

The reason everyone is watching Evergrande today, and not some other day, is that the company faces an interest payment of $83.5 million on dollar-denominated debt. That payment was due today, Sept. 23, to bondholders, including Ashmore, UBS and HSBC. Whether Evergrande will make the payment is at this point in grave doubt.

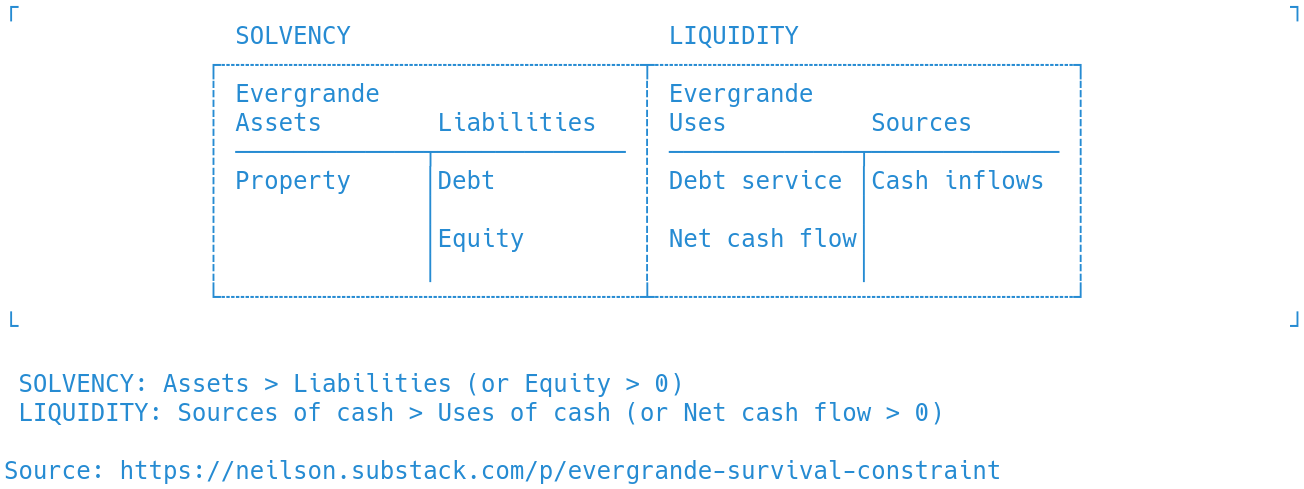

As Evergrande is demonstrating, it is one thing to take on a lot of debt, and another thing entirely to miss a payment. Too much debt, or more concretely liabilities in excess of assets, is called insolvency. Missing a payment, or more concretely cash commitments in excess of cash inflows, is called illiquidity. This can be illustrated in accounting terms, with the solvency view on the left using assets and liabilities, the liquidity view on the right using sources and uses:

It is quite possible for an insolvent company to continue to operate. With cash on hand, wage, expense, and even debt commitments can be honored and activity can continue, no matter whether liabilities are greater than assets. But an illiquid company will struggle mightily to carry on: without cash, it cannot pay employees, suppliers, or lenders, who will promptly seek remedy in the legal system. The intensity of the looming deadline, including comparisons to Lehman Brothers, has everything to do with the drama of a liquidity crisis. Evergrande is in all likelihood both insolvent and illiquid. But they have probably been insolvent for some time, and they are illiquid now.

There is a name for the problem Evergrande faces today: the survival constraint. That is the name that Hyman Minsky gave to the basic cash-flow constraint of an economic system based on payment. If payment is to mean anything, then eventually debts must be settled using money. If a payment is missed, and no accommodation is made by the lender, then the firm's survival is immediately in question. That constraint, articulated by Minsky in his doctoral dissertation and never mentioned by that name again, is nonetheless, I have argued, his key insight, the one from which the others all follow.

How illiquidity becomes systemic

The Evergrande situation shows us how this is so. We are this week confronting the possibility that a payment missed by the company will cause other companies to miss their own payments, spreading financial troubles more widely and, in the most extreme scenario, setting off a cascade reminiscent of the crisis of 2008. Whether that comes to pass or not, the value of the liquidity lens is that it gives a way to understand how such a systemic event could happen.

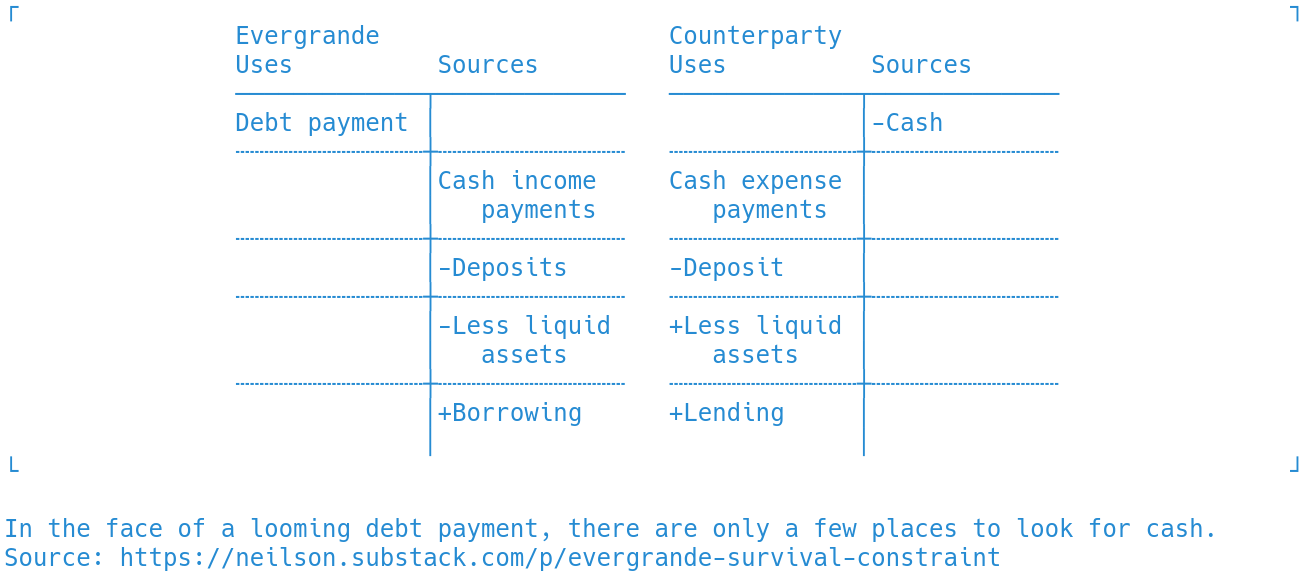

The survival constraint says that if a promised payment is not made, the firm will face its consequences in the legal system, up to and including the company's survival. Evergrande, like anyone who faces a looming payment, has little choice but to look for sources of cash. A big company might look in many places in its operations for spare change, but at a high level there are really only a few possibilities, as these T accounts show (in a sources and uses framework):

Evergrande needs cash to make its debt payment. If all were well with its main business of property development, the company might simply sell properties and use the cash to pay its debts. That time is past. If there were money in the bank, then those deposit balances could be run down to pay the expenses. But that too is out of reach. Evergrande might generate funds by selling off assets, which it has been trying to do. But at fire sale prices, it is too little too late. Borrowing through normal channels is now closed as well, though given the company's systemic position, a government guarantee might support a loan, probably on punitive terms.

Importantly, and as the T accounts above illustrate, anything that can be a source of funds for Evergrande must be a use of funds for someone else, some yet-to-be-determined domestic or international counterparty. That counterparty, in turn, must have its own source of funds in order to be able to step in. In other words, any of these solutions to Evergrande's illiquidity requires that someone else be liquid.

Systemic event?

This is the crux of the matter, from the point of view of systemic stability. It might be that someone with cash on hand will see a way to stepping in. Indeed, another payment also due this week was "resolved through off-exchange negotiations." Perhaps the Chinese government, or the People's Bank of China, fearing systemic instability, will mobilize the apparatus of the state to provide the funds. But Evergrande needs the cash now, and it will have to come from somewhere. Whether this becomes a broader financial crisis has everything to do with who ends up being the source of cash, and what survival constraint they face in their turn.

Perfect

A question I've wanted to ask since I first learned of the term "survival constraint" in Perry Mehrling's first run of the Economics of Money and Banking MOOC in 2012: what is the Fed's survival constraint? Where does the Fed get its liquidity to pay 5 basis points on Reverse Repo? Where does the Fed get the liquidity to buy unlimited amounts of financial assets from private firms?

Also, isn't contagion the key systemic risk with Evergrande, rather than the cascading microeconomic effects you focus on? If confidence channels undermine other Chinese developers, would that be like traders panicking in 2008 and selling off even rock-solid assets with no exposure to Lehman?

Is the latter contagion story unpalatable, because it strongly implies prices are arbitrary, as Fischer Black noted in "Noise" (which I was also introduced to in Mehrling's MOOC)?