The Fed's CBDC paper

A balance-sheet framework

Last week the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve released a discussion paper on a prospective US central bank digital currency (CBDC). CBDCs are already a reality in some jurisdictions and are being evaluated in others. They are meant to combine the convenience of electronic payments with the settlement finality of banknotes.

The paper puts the issue into a historical-technological narrative of the payments system, citing centralized domestic check-clearing in the US (early 20th century), automated clearing of paper checks (1970s), and real-time always-on interbank payments (launching 2023). Infrastructural changes, that is, in which the foremost goal is to not be disruptive.

By looking at the balance-sheet consequences of the introduction of a US dollar CBDC, this post offers a transactional scaffolding on which we can hang the many questions still to come about the politics and economics of CBDC.

How would the public come to hold CBDC?

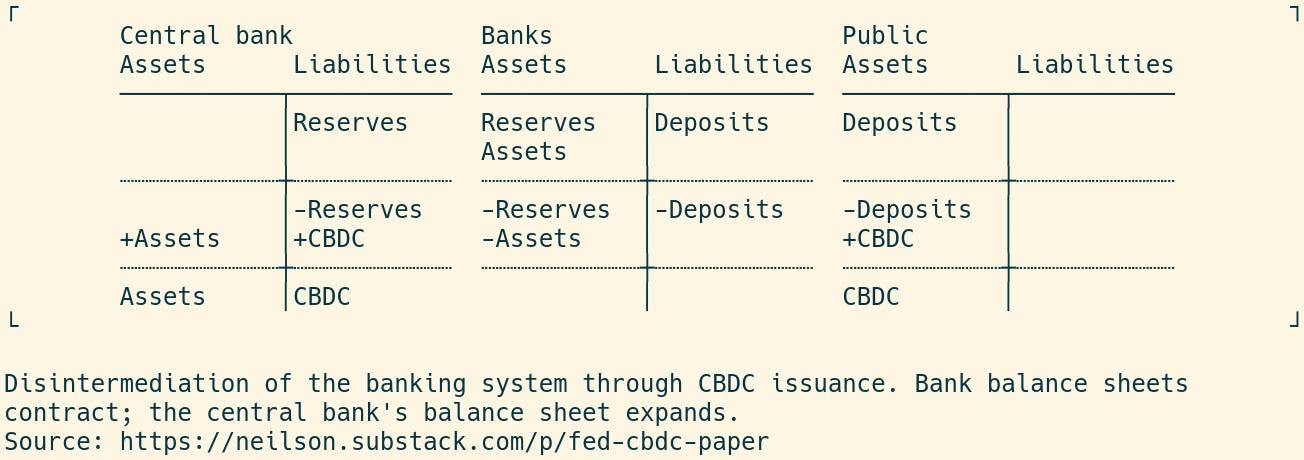

To be able to talk about CBDC, a useful starting point is to sketch out how the public would enter into the balance-sheet position. In other words, how would the public shift from its current asset holdings so as to become holders of digital claims on the central bank? These T accounts depict one possibility for such a migration. The public sells bank deposits and uses the proceeds to buy CBDC. The banks would likely operate CBDC wallets for their customers—for example through their mobile apps—but the underlying claim would be on the Fed:

What happens to bank balance sheets? First possibility, as shown here: banks reduce reserves accordingly. Banks would also sell other assets, depending on the scale of the drawdown. Simplest case, the central bank buys the assets, and bank balance sheets shrink: bank disintermediation.

Such a scenario could play out quickly, in a crisis, or methodically, as part of a reconstruction of the US financial system. Saule Omarova, a legal scholar and the Biden administration's first nominee for Comptroller of the Currency (one of the key US bank regulators), advocated doing the latter. Her paper "The People's Ledger" proposed using CBDCs to reduce the size and power of the private financial system, expanding the size and power of the central bank in the allocation of domestic credit. Omarova's nomination late in 2021, notably, was quickly disposed of by Republican senators and bank lobbyists.

We might reasonably conclude that there is not currently political will in the US for such bank disintermediation as the outcome of a methodical process. But the central bank's balance sheet has undergone major change more typically as a result of crisis than as part of a comprehensive plan. The transactions represented in the T accounts above could instead play out quickly, in crisis.

Second possibility: the central bank might choose instead to to refinance the banks' position, lending to the banks to prevent their balance sheets from contracting. Such a situation could look like this:

Banks get to keep their asset portfolios, but now instead of accepting unsecured deposits from the public, they accept repo deposits from the central bank. This shift could also happen either methodically or in a crisis, and for the same reasons as above, I think any big shift is more likely to happen in a crisis.

And so

The main objections to CBDC that the Fed's paper raises are variations on these themes. The section on "Financial Market Structure," for example, is about slow bank disintermediation. The section on "Stability of the Financial System" is about fast bank disintermediation. The section on monetary policy implementation is about the availability of reserves, and, more generally, the interactions of CBDC funding channels with existing money-market instruments.

There other concerns as well, concerns that go beyond the transaction structure as I've been discussing it here. The paper makes clear, for example, that the Fed will not move ahead without specific support from the US executive and legislature. The Fed also says little about where CBDCs fit into questions about crypto, instead simply pointing to last year's Stablecoin Report. Much more still to be said.

I'm trying to flesh out my intuition for these balance sheets.

Could we break it into two steps where both sets of balance sheets share the same first step?

The first step, then, is that the public withdraws its deposits in favor of CBDC thereby draining reserves from the banks. This leaves the banks in a situation where their assets are funded by deposits and they have no reserves.

In scenario one, the central bank replaces banks' assets with new reserves, and the drain of reserves and deposits repeats itself until the banks have nothing.

In scenario two, the central bank lends reserves to the banks through the repo market rather than buying the banks' assets. The drain of reserves and deposits repeats itself until the banks are just left with repo funding their assets.

So the difference is whether:

1. The central bank buys the banks' assets directly by issuing reserves, or

2. The central bank indirectly finances the banks' assets through the repo market.

Is that right?