The Fed in the repo market

The ascent of market-based finance, pre-2008 to the present

Both the 2008 crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic have come in the context of an ongoing shift of global finance toward market-based credit. Borrowing and lending is increasingly effected through the purchase and sale of securities, rather than through lending and borrowing. This context is essential for understanding the consequences of these events for the financial system.

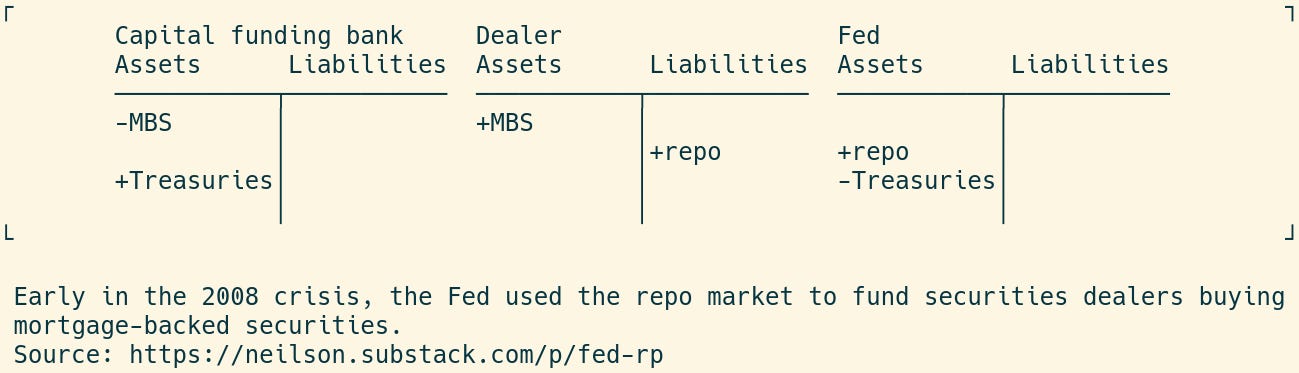

Market-based credit is built around a key currency, the US dollar, and a key money market, the repo market. In a repo transaction, loans of money are collateralized by deposits of securities. The US Federal Reserve, as the administrator of the dollar and therefore of the market-based credit system, has in recent years undertaken major transactions in repo markets. Those transactions have taken different forms according to circumstances. Below, I outline the Fed's engagement with the repo markets, from just before the 2008 crisis up to the standing facilities established this year.

Before 2008: targeting the Fed Funds rate

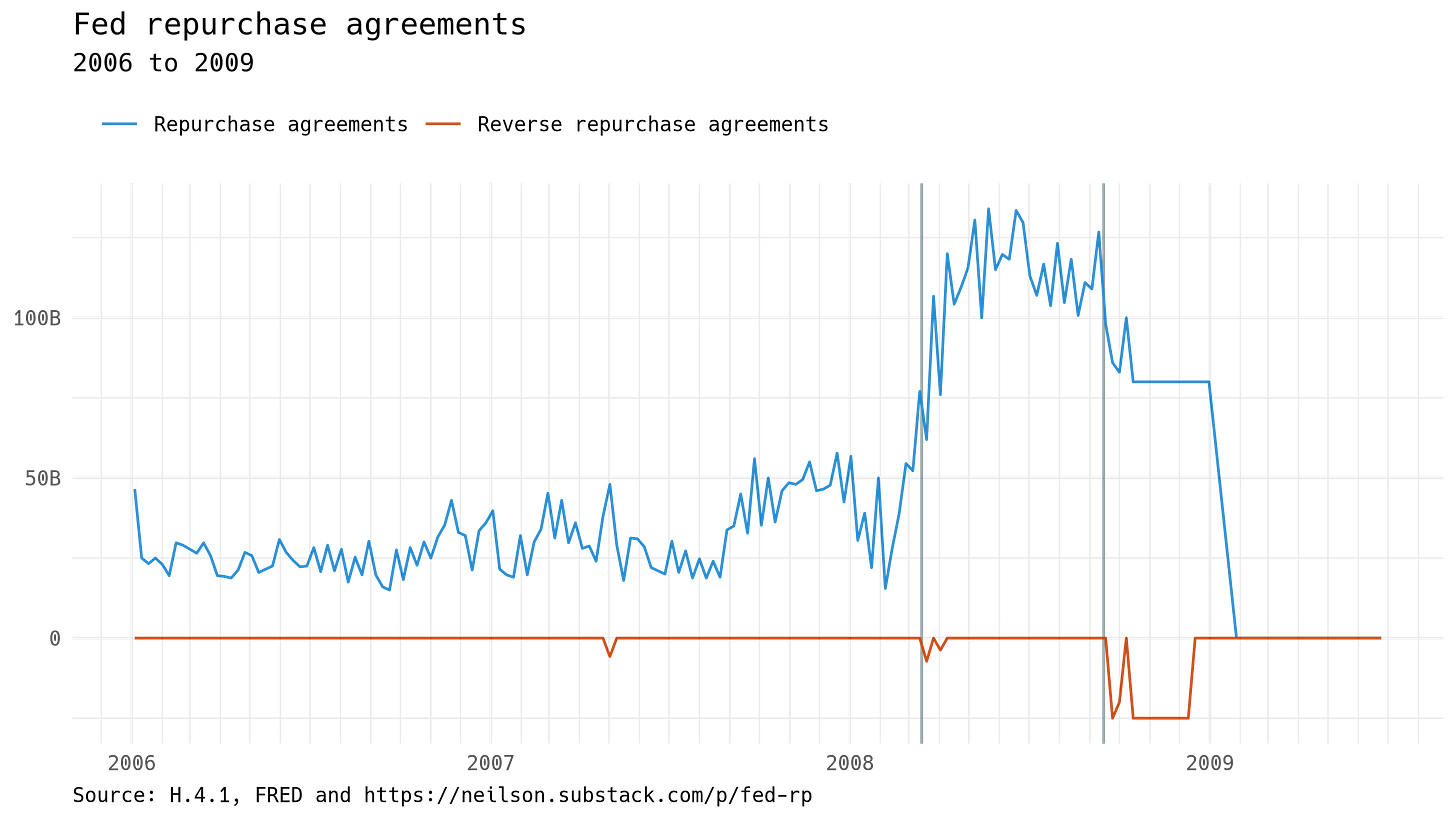

This graph shows the Fed's activity in the repo markets, beginning before the 2008 crisis and continuing until early 2009. The blue line shows the Fed's repo lending; the red line shows the Fed's acceptance of repo deposits (written as a negative number to show that it is on the opposite side of the balance sheet). The two vertical lines in 2008 mark the failures of Bear Stearns (in March) and Lehman Brothers (September), which I have used elsewhere to divide the crisis into phases.

Prior to the 2008 crisis, the Fed's repo lending shows some volatility, but around a stable low level, less than $50 billion on a then $1 trillion balance sheet. During this period, the Fed routinely lent in the repo market as a way to manage the availability of bank reserves. Banks were free to lend these reserves to one another in the federal funds market, and until the crisis, the Fed was able to implement its target for the Federal Funds rate using such transactions.

Importantly, the Fed undertook these repo transactions on its own initiative: the central bank prepared estimates of the reserves that would be needed, and it determined the scale of repo operations with this estimate in mind. Fed traders would, on most business days, transact in the repo markets to supply reserves.

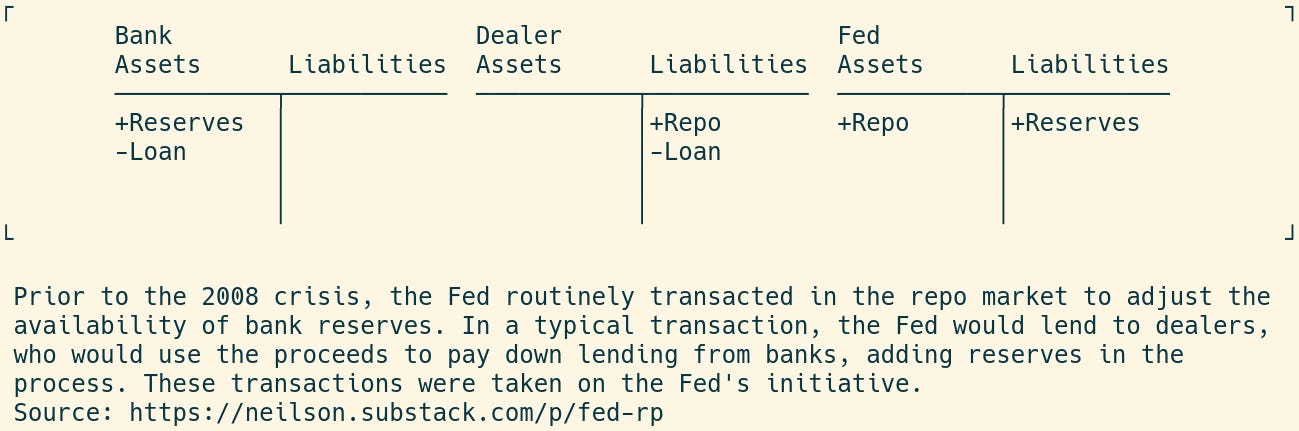

The 2008 crisis: funding the exit from mortgage-backed securities

One of the major dynamics of the 2008 crisis, especially during its early stages, was that financing vehicles could no longer roll over their borrowing in the asset-backed commercial paper market. Without financing, they were forced to sell their positions in mortgage-backed securities. Securities dealers were the main buyers of MBS, but they too found it difficult to finance these securities of questionable value. The Fed was already in the repo markets daily, and in the middle of 2008, in response to the emerging crisis, it expanded its repo lending to support dealer financing. The transactions can be illustrated like this:

Later in the crisis, the Fed began to purchase mortgage-backed securities directly. It did so by significantly expanding bank reserves, and so there was no need to lend further reserves into the system. In fact, the central bank even absorbed a small amount of reserves using reverse repo transactions at this time. The graph above shows these shifts, and the end of the Fed's use of repo by early 2009.

The development of the reverse repo facility

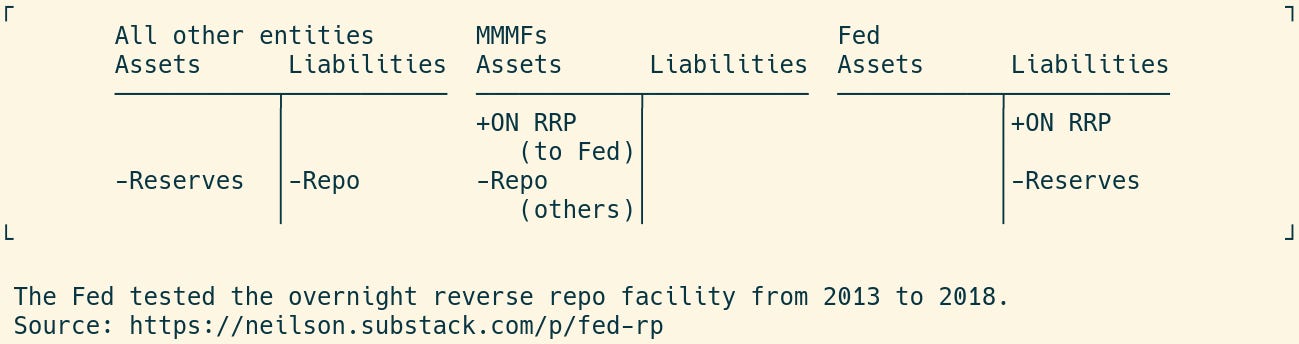

One consequence of the 2008 crisis was that the Fed moved from a scarce-reserves framework to a plentiful-reserves framework. The creation of reserves to purchase mortgage securities meant that banks now had large reserve balances. Concerned about the possibility of rates falling too low, the Fed began testing a reverse repo facility to set a floor under interest rates:

As the graph shows, this experiment with a reserve-absorbing facility did reach a significant level of usage. The balance-sheet context, at this time, was one of stable and eventually contracting asset holdings, so we could summarize the transactions in T accounts like this:

September 2019 repo interventions

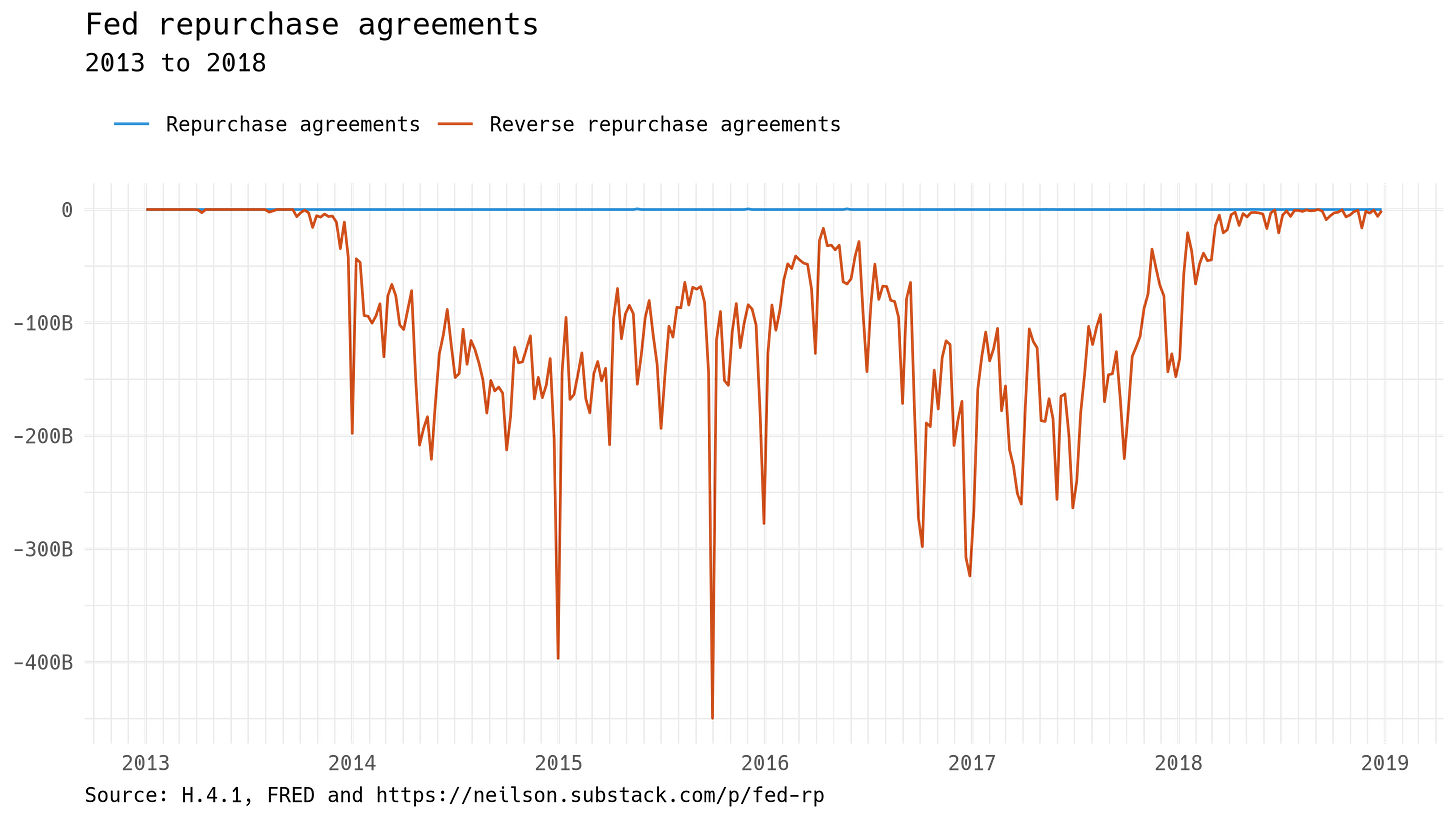

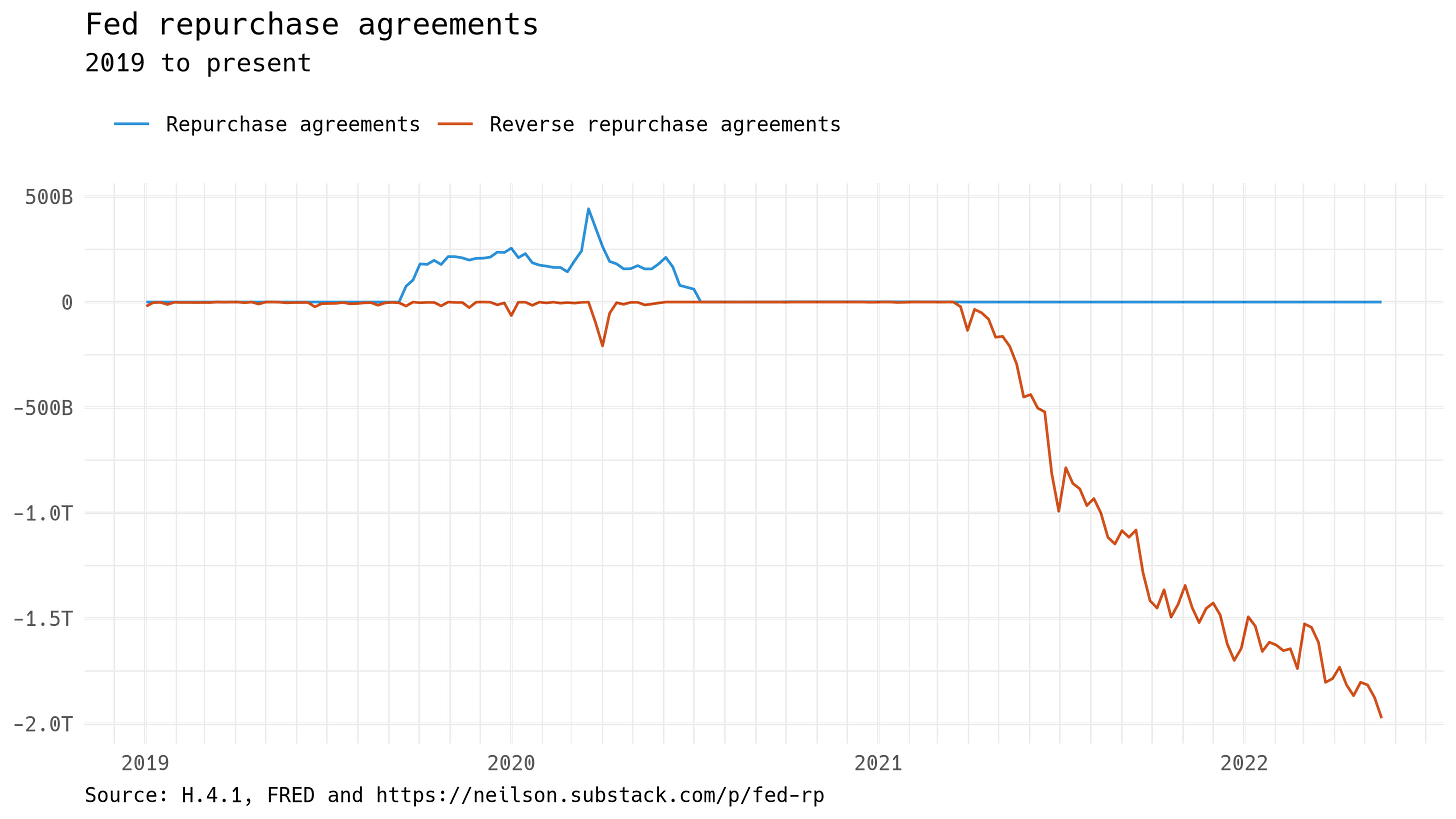

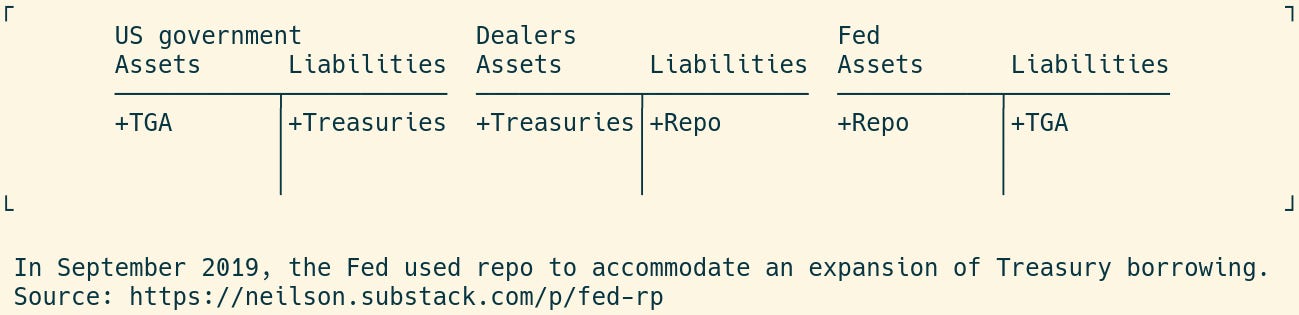

This graph shows the Fed's transactions in the repo market from 2019 to the present. The central bank re-entered the repo market as a lender in September 2019. The intervention followed a dramatic spike in repo rates, due, it seems, to the Fed's attempts to shrink its balance sheet, coinciding with the US Treasury's expansion of its cash balances against new borrowing. The two events reduced the cash available for lending in the repo market. After rates spiked, the Fed provided funds:

2021: absorbing reserves

The September 2019 intervention was still underway when the COVID-19 pandemic became a global phenomenon in March 2020. Early in the pandemic, the Fed expanded its intermediation on both sides of the repo market, both as lender (with repo transactions, an asset to the Federal Reserve) and as borrower (with reverse repo transactions, a liability to the Fed).

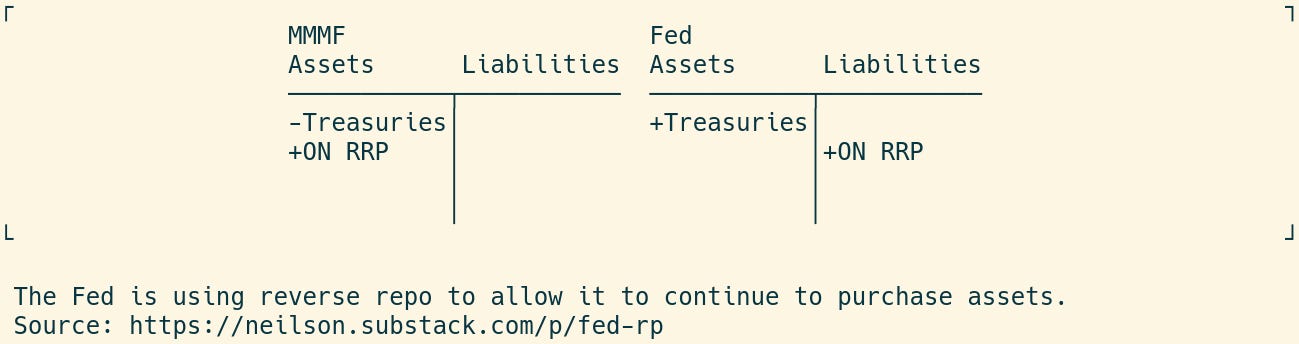

More recently, the Fed is in repo markets as a borrower (i.e., it is accepting deposits). Ongoing asset purchases continue to add reserves to the financial system. Banks are unwilling and increasingly unable to hold more reserves, so the Fed has re-established the ON RRP facility as a channel to absorb those reserves. At present, the marginal overnight reverse repo transaction is this:

Future: standing repo facilities

These changes in the Fed's relationship to the repo markets have much to do with the development and importance of the market-based credit system. Financial activity is increasingly based on the exchange of marketable securities, rather than loans, and repo is the generic lending transaction that supports the holding of these securities.

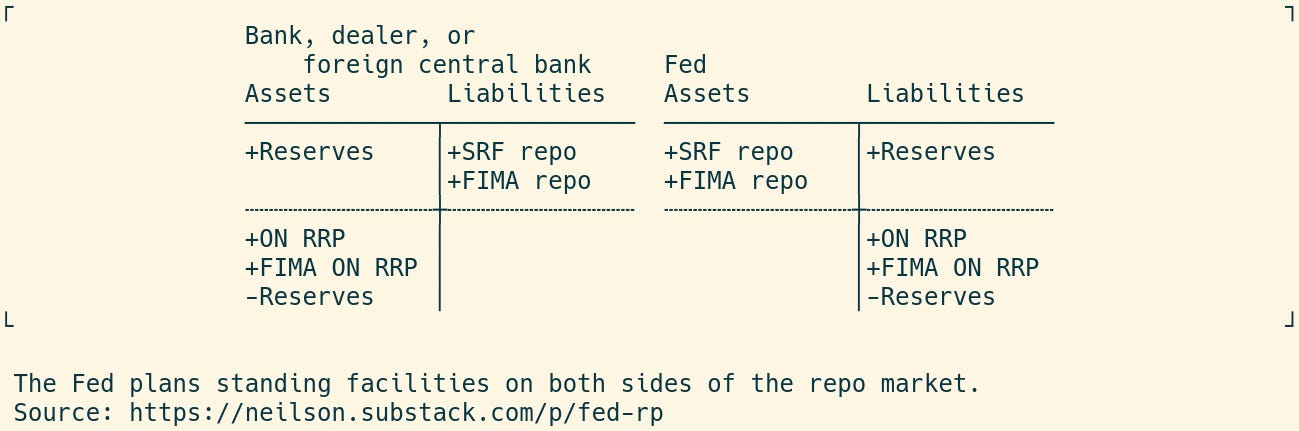

Recently, the US central bank has moved to establish standing repo facilities. There are four such mechanisms—two for borrowing and two for lending, with separate facilities on each side for domestic and international counterparties.

With these standing facilities, the Fed will complete its return to the repo market. But before the 2008 crisis, the Fed was in the market on its own initiative; importantly, the new standing facilities will all transact when the Fed's counterparties want to. Rather than making the market price directly, the Fed wants private market-makers to set the price, and for its standing facilities to only come into play when the private market-making breaks down. This, I think, marks a clear shift in the central bank's stance toward market-based credit, and one which will prove to have long-running effects.