How to Read Soon Parted

Thanks for reading Soon Parted! I thought I would take a minute to say a bit about how I write this newsletter, and offer some advice on how to read it.

What is Soon Parted?

This is a newsletter/blog about money, banking and the financial system. Twice a week, I offer a few hundred words and a couple of pictures based on the news, or on breaking down a big idea, or on a piece of financial history that has useful lessons. I like to think that Soon Parted is distinctive in three ways:

I don't have a theoretical axe to grind. I'm trying to make sense of what's happening. To be sure, there is economic theory that is relevant, and I do have my views, but the point is what's happening, not the theory.

Soon Parted is not about making normative judgments. I don't really ever say what I think investors, regulators, policymakers or economists should do, or how I think things should work. That's not because I don't have strong opinions (which I do!). It's because I think the conversation could be improved if the mechanisms of finance were more widely understood, and that purpose would be obscured if I were always trying to push a certain solution.

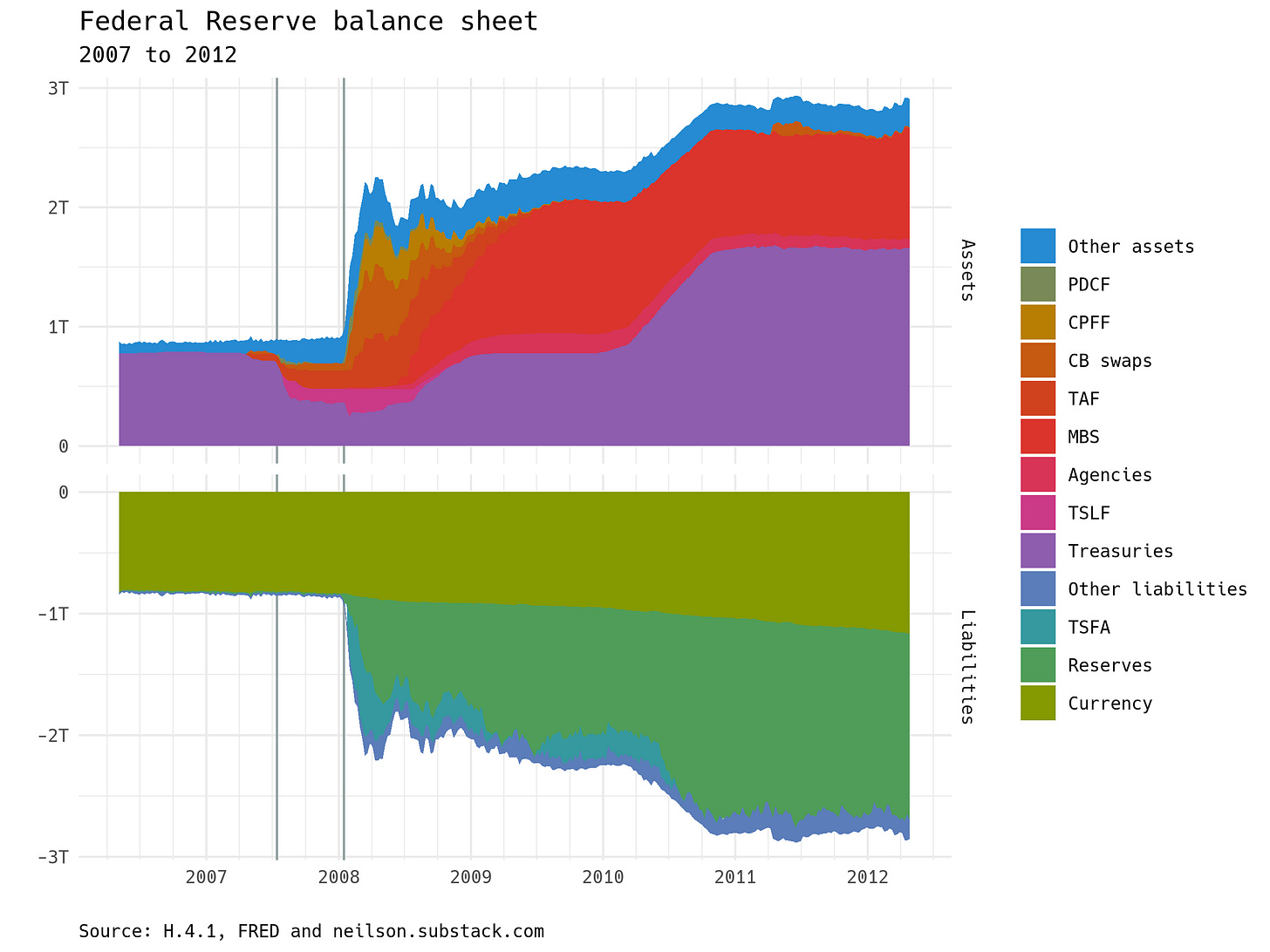

I put some time into making nice visuals, usually either graphs (which I do in R using ggplot2) or T accounts, on which more below. I also make animated gifs, mostly for twitter. The visuals are usually the scaffolding of my posts, constructed first and sequenced to convey the main point. Some of my favorites manage to tell pretty detailed stories in a small space, like this one:

What is up with all the T accounts?

I rarely use equations in Soon Parted, but there is one technical tool that I use all the time without much explanation or justification: T accounts. A T account is a visualization of the balance sheet, the statement of assets and liabilities, of an economic unit.

Explanation In the left column are assets: what the unit owns. In the right column are liabilities: what it owes. It is helpful to put them side by side, in an organized way, to show relationships between assets and liabilities. Here is an example that was particularly important in the 2008 crisis:

What this says is that there is a capital funding bank (or "shadow bank") that owns a portfolio of mortgage-backed securities. These are financed by borrowing in the asset-backed commercial paper market. The ABCP is held as an investment by a money market mutual fund, which in turn finances its own position by issuing deposits (in the form of shares). There are two entities and so two T accounts. There are three instruments (MBS, ABCP, and deposits), of which only ABCP is fully represented here. The mortgage securities are someone else's liability, and the deposits are someone else's asset. The other sides are not shown, which is my choice to focus in on a certain part of the situation.

As I have written them, these T accounts show financial positions at a point in time. They say nothing about how those positions came to be. Sometimes the history doesn't matter and it is helpful to strip it away. Other times the steps may be important, and they can be shown using plus and minus symbols in the T accounts to show things moving around.

Justification All of this is a bare-bones version of the same double-entry bookkeeping that accountants and economists have used for centuries, applied at a macroeconomic scale. What it says is that money comes from somewhere (income or borrowing) and goes somewhere (spending or lending). If you want to understand money, banking, and finance, it turns out, you can get more than halfway just by being clear about who owes what to whom and under what circumstances.

(That statement is also true of a failed scheme after its bankruptcy, or of a popped bubble after a financial crisis. I suppose that's the best rationale I can offer for this newsletter's name.)

With Soon Parted, I have taken the principled position of assuming that readers can decipher a T account, or are willing to be patient and puzzle it out. Considerable experience says that the effort is well worth it: if you can write out the T accounts for whatever problem is in front of you, you do understand what is going on or pretty close; if you can't write out the T accounts, you probably don't. But even better, the problem is self-correcting: if you can't yet write out the T accounts, and you set about trying to, you will probably end up by understanding.

Anyway, enough talk. If you are not convinced, please keep reading Soon Parted and I hope you will come to share my conviction.

I would like to learn more

I first learned how to think about money and finance from Perry Mehrling, when I was his TA (and later co-author and colleague) as a grad student. At first I only understood a little. I kept at it, and I came to understand more. If you want to take a class and study money and banking according to a syllabus, you should follow his course. Perry is a great thinker and a great teacher.

Other than that, my recommendation is that you find a couple of good sources and read them regularly. The Financial Times is my newspaper of choice, as should be obvious if you have ever clicked on links in my posts. The Bank for International Settlements, the central bankers' central bank, has a truly unique window onto the operation of global capitalism. Anyone who reads even one article from each BIS Quarterly Review will not be able to avoid becoming quite well informed.

How can I support Soon Parted?

My appreciations to Substack for providing the platform. Substack's business model is for writers to offer paid subscriptions, from which they deduct a fee. I don't have any plans to introduce paid subscriptions in the near future (though I haven't ruled it out either), but I am interested in building Soon Parted's audience. If you want to support that goal, here is what you can do.

Share, retweet, pass along. The vast majority of the readership of Soon Parted found it because someone else shared a piece that interested them.

If you have access to a platform of your own and would like to have me as a guest, please reach out.

Send your questions or comments. If you read a piece and are left with a question, please ask it! It is very helpful to know when I have failed to make sense. Or if you have additional perspective, or if you think I'm just plain wrong, please let me know. I'm bound to make mistakes—please help me not make the same mistake twice. It's easiest to reach me by responding to a newsletter email or on Twitter (@dhneilson). These days it's hard to respond personally to every query, but keep reading and I will get back to you in a future post.

Next time I’ll get back to it. Thanks again for reading!

"money comes from somewhere (income or borrowing) and goes somewhere (spending or lending). "

Doesn't this gloss over the fact that the monetary expansion in the Fed's balance sheet, as represented in the first figure in the blog, came from nowhere?

Your blog has been very helpful for me to understand how money and banking operate. I hope you get back soon. From Korean follower