Recent financial news from Turkey has been dramatic as the central bank has struggled for stability. As foreign capital has exited positions in Turkish assets, private market-making in foreign exchange has tended to depress the price of lira against dollars. The difficulty has shown up in prices for dollar–lira FX swaps, shortselling fines for international banks, and closures of Turkish cryptocurrency exchanges.

The central bank's objective is to support production and prevent capital outflow while containing domestic inflation. This puts the central bank on a tightrope. Simply raising interest rates limits domestic production and raises political hackles. But CBRT's recent interventions in foreign exchange have failed to support the USD price of the lira. Turkish businesses face input costs denominated in dollars, so the falling lira also risks spilling over into domestic inflation. The failure of the interventions has also prompted speculation as to the misuse of reserves.

The CBRT's task is difficult for many reasons. I do not at all discount the complexity of the country's situation. But one big constraint, somewhat separable from politics, is that it is very hard for a central bank to affect an exchange rate when the country has an open capital account. In this edition of Soon Parted, I want to make some sense of this difficulty as it relates to Turkey's situation.

Closed capital account

Start with a simpler arrangement, very different from Turkey's: an open trade account with a closed capital account. Imports of goods and services move with few restrictions, but cross-border financial arrangements are limited. More specifically, suppose that domestic residents are prevented from holding foreign exchange. In such a system, when locals sell exports for foreign money, they are required to exchange it for domestic currency at the central bank. Likewise, foreign residents are prevented from holding domestic money.

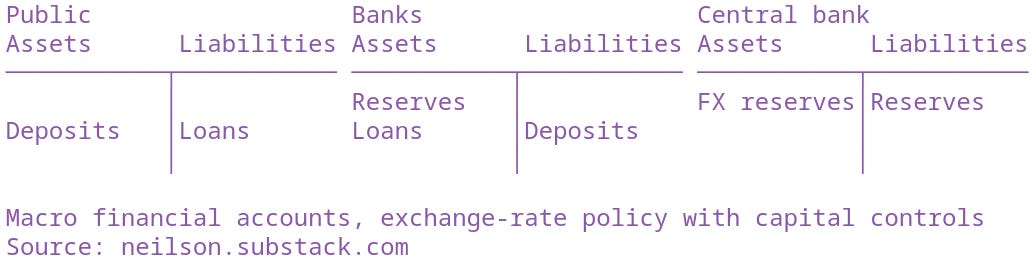

This is more or less the situation in China, a major trading nation with strong restrictions on capital flows. It gives the central bank tight control over the exchange rate. Sectoral balance sheets look something like this:

Everything is denominated in local currency except the central bank’s FX reserves. The point is that only the central bank, and no other actor, has a position both in foreign exchange and in domestic money. It is therefore in a position to set the price on which the two are exchanged for one another—the exchange rate. This doesn’t eliminate the problem of striking a balance between domestic inflation and economic growth, but it does mean that the central bank is in a position to set and achieve a target.

The trade-off that these limits bring is that the public may find the controls to be restrictive.

Open capital account

In Turkey, by contrast, the general public is free to hold foreign exchange. The Turkish central bank has tried, and increasingly failed, to limit the fall of the lira by intervening in foreign exchange markets. Such an intervention is inherently more difficult with open capital flows.

The basic financial structure is something like this:

The public holds accounts with Turkish banks denominated both in foreign currency and in lira. The central bank accepts reserve deposits from its banking system denominated both in foreign currency and in lira. In effect, there are two domestic banking systems, one denominated in lira and the other in foreign exchange.

The central bank would like to prevent the lira from depreciating. It tries to do this by contracting supply, buying lira and selling FX reserves. But the open capital account means that the public is free to take the other side of this trade. So rather than exerting pressure on the exchange rate as intended, the interventions leak out onto other balance sheets. CBRT cannot contain the lira's fall because other domestic balance sheets absorb its interventions.

This explains the CBRT's need to borrow foreign exchange from its banks to fund its FX interventions. The Turkish treasury, likewise, has been selling foreign exchange-denominated bonds, apparently as another way to borrow banks' FX reserves. Aside from the lack of transparency, these efforts are likely to fail. CBRT faces a more basic problem: trying to control a price without control of the relevant balance sheets.

In sum

I don't mean to oversimplify the situation—there are a lot of factors, competing interests, politics and history at play.

But the exchange-rate interventions all tell the same story: the central bank is trying to control a price without sufficient leverage over the relevant balance sheets. Its attempts fall short and the CBRT has had to resort to ever more dubious deals to get access to foreign exchange. Instead of getting traction on the price, the central bank is only succeeding at rotating FX among domestic balance sheets.

Please subscribe

Soon Parted is a newsletter about banking and finance. I look at issues related to financial crises, fintech, crypto, and central banking. If you liked this post, please subscribe to the receive updates:

For example, in a 2012 blog entry (Delicate balance) you wrote: "Take first the issue of U.S.–China bilateral flows of trade and capital. The net flows can be described easily: China runs an export surplus, and its central bank, wishing to prevent appreciation, absorbs the resulting net capital flows." How would they go about doing this? What is the "plumbing" mechanism?

Let me try to clear my question, it seems a little loose. I'm writing from Brazil, where exchange rates were fixed in the past but now works in an administered band regime. I'm interested in understanding the nuts and bolts of administering an fixed exchange rate and also the current administered bands regime. Can you point me to some articles using the same money view and balance sheets where I can get a deeper understanting?