Money funds

March 2020 in the money markets

The Fed doesn't transact with everyone. When the central bank develops a new balance-sheet line with a new set of counterparties, that is both a sign that things have changed and an indication that they will continue to do so.

Starting in March 2021, usage of the Fed's overnight reverse repo facility has made money market mutual funds into a significant part of monetary policymaking.

The expansion of the ON RRP facility at this point in the pandemic is a new twist in the recent evolution of money funds. This post offers a snapshot of changes to money funds since 2016. That perspective sheds some light on the events of March 2020, when the implications of the early spread of COVID-19 became widely recognized. During that period, money markets reflected the disruptions taking place everywhere.

I have spent too much time reading and making graphs for this post, so it is heavy on pictures and light on words. But money funds are proving to be quite central to monetary policy, so I will certainly be coming back to it in future posts.

2014 money fund reforms

A set of reforms following the 2008 crisis led to a significant portfolio adjustment for money funds when the new rules came into effect in late 2016. These rules divided MMMFs into two classes. Government funds were permitted to issue constant net asset value (CNAV) shares, intended to trade at a fixed price of one dollar per share, but they could invest only in a limited range of assets, mainly government securities and repo backed by government securities. Prime funds, by contrast, could hold a wider range of securities, but could issue only variable net asset value shares.

Money funds were and are a central intermediary of the market-based credit system: both their liabilities and their assets take the form of securities. MMMF liabilities are among the most money-like assets of the market-based credit system, but only when markets are liquid. When money funds came under strain in the 2008 crisis, it was disruptive exactly as bank failures would be.

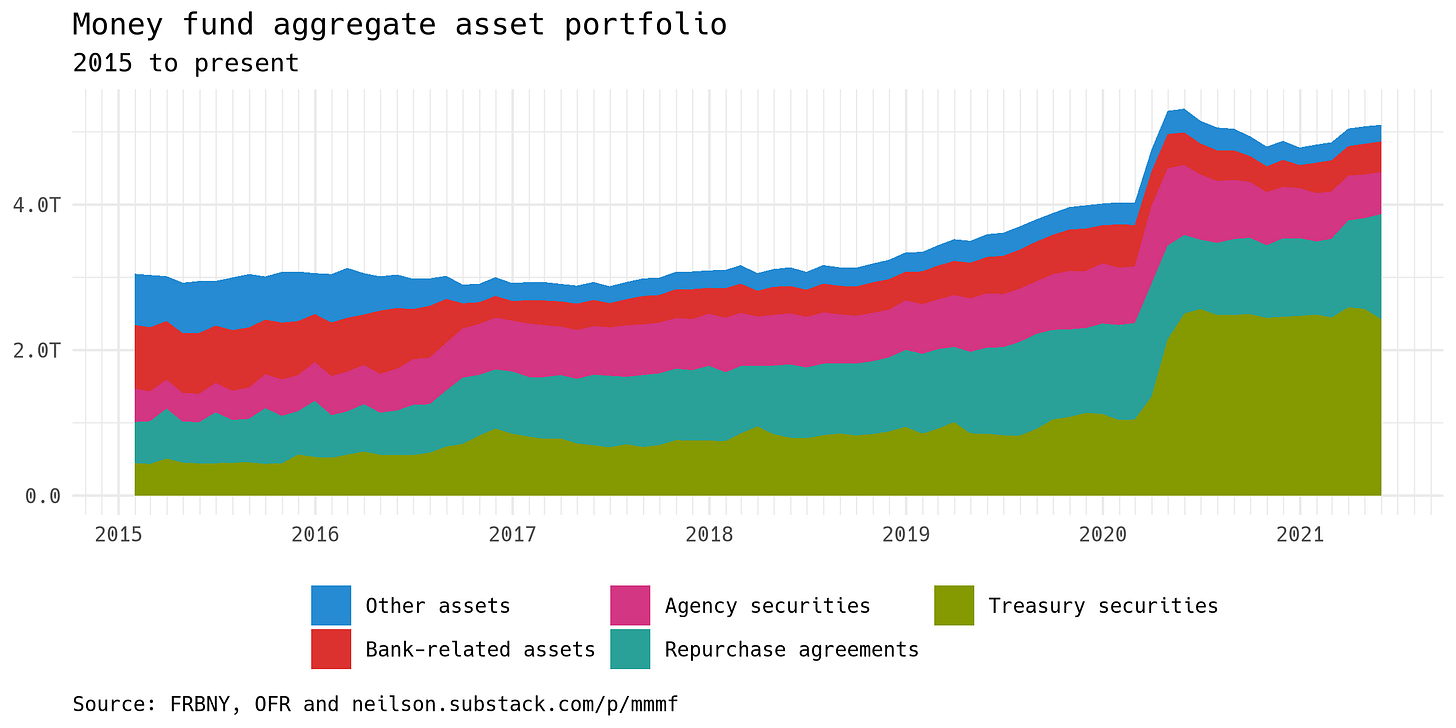

The 2014 reforms sought to constrain money funds so that they would be less likely to be a vector for financial instability. In 2016, when those reforms came into effect, money fund investors had to choose between the money-like CNAV government funds and the higher-yielding but VNAV prime funds. In the event, moneyness won out: overall, investors shifted funds from prime to government money funds. As a result, the aggregate asset portfolio of all money funds was remained the same size, but rebalanced toward Treasury securities. The reallocation is clearly visible in late 2016 in this graph:

March 2020

This was more or less the state of affairs going into 2020. Starting in March, as the world came to recognize the implications of the spread of COVID-19, investors shifted some $1.5 trillion into government money funds, which in turn purchased a corresponding volume of Treasuries.

Prime money funds, meanwhile, were shifting out of riskier assets, which led in particular to stress in the commercial paper market. With about $1 trillion outstanding at any given time, the unsecured commercial paper market is an important source of short-term financing for US and non-US banks and for US non-bank corporates. In March 2020, prime money funds were reducing their CP holdings, particularly of paper issued by non-US banks. The contraction can be seen in this graph of commercial paper outstanding:

Not only were overall levels of commercial paper contract, but the tenor also shortened as money funds sought to reckon with a suddenly-less-certain future. Mid-March 2020 saw a dramatic shift toward overnight issuance and away from all longer terms. This reduction in maturities was very similar to the early stages of the 2008 crisis, when interbank lending took place only on an overnight basis.

Pivotal intermediary

March 2020 was a pretty grim month all around. As is frequently the case, collective adjustment to a rapidly changing reality was reflected in large flows through disorganized money markets. A year and a bit later, money funds are holding the liabilities needed to allow the Fed to continue to expand its assets. At two key moments in the pandemic, money market funds have proven to be the pivotal intermediary. This story still has room to run.