Netting

A correspondent wrote this piece, which brought my attention to transaction netting. Netting—aggregating offsetting transactions—is always in the background in my Money View of the financial system: it was present in a recent discussion about whether CBDCs might not flatten the monetary hierarchy; it also showed up in some of Izabella Kaminska's work on real time gross settlement. As my correspondent shows, the question of netting also clarifies certain crypto debates. All this prompts me to put netting into the foreground.

Netting: a simple case with only two balance sheets

Start with a minimal example, using the balance sheets of only two entities, Alpha and Beta. Suppose that these entities routinely incur debts to one another, in both directions. This might be an unlikely premise for payments associated with production, where the orientation of supply and production chains generally means that payments mostly go in one direction. But for the majority of payments—the gross flows associated with finance─it is not a big stretch.

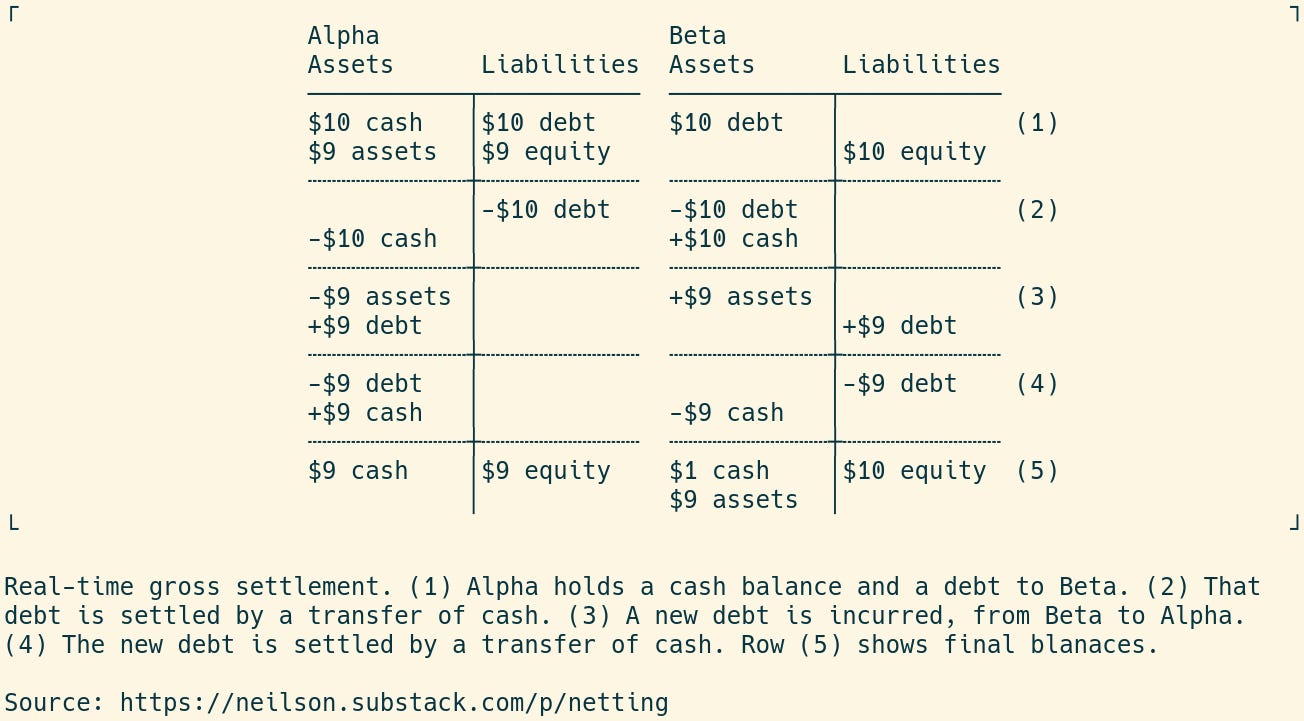

The T accounts below illustrate a simple situation in which netting can arise. Alpha starts out (1) with $10 cash and a debt of the same size, to Beta. Beta carries equity against this exposure. Alpha also holds $9 in assets, supported by equity. Alpha immediately settles the debt (2) by transferring cash to Beta. Now, in a new transaction, Alpha sells $9 in assets to Beta (3), creating a debt from Beta to Alpha. Again they settle immediately (4) through a transfer of cash:

This captures something of a real-time gross settlement (RTGS) system: every debt must be resolved in real time, by transfer of the payment medium, cash in this case. In the example above, two cash transactions were required to settle two debts. The biggest was valued at $10, and so there had to be at least that much cash in the system for the payments to go through.

There is another way to go about it. Suppose that, instead of settling the first debt, Alpha and Beta allow it to remain on their balance sheets. Then, after the second debt comes along (2), the two debts can be set off each other, and only the remainder of $1 needs to be settled in cash:

This is netting: the same two debts get paid, but the settlement process is different. Only a single transfer of cash is required, and only the net amount had to be paid. Netting reduces the cash needed to only $1, versus $10 for the same payments without netting.

Tentative conclusions

As my correspondent Johnny Foolish notes, netting economizes on capital: in the example above, the lower cash requirements mean that the net settlement arrangements use only $10 equity, versus $19 needed under gross settlement. For this reason, traditional finance has often preferred to net where possible.

But it was in an effort to reduce not capital but counterparty risk that prompted an actual shift to real-time settlement Under gross settlement, that is, the parties spend less time exposed to one another. This reduction in what is known as Herstatt risk has been, in some cases at least, at least as compelling as reducing capital.

What this suggests is that the choice between net and gross settlement arrangements amounts to a choice between different configurations of loss-absorbing capital. Which form is the more stable would depend, it seems, on many factors, including how payments normally net out, and what kinds of losses the system normally faces.

Hi - I'm Chris from the Money View symposium. I thought I'd check in on your work.

Mind if I criticise your use of a couple of phrases related to equity? I hope not, because I'm doing it now... :-) I think there's a crucial conceptual point here.

"Beta carries [$10 of] equity against this exposure". Beta doesn't have any exposure. It has a (debt) asset, which may or may not involve Beta being paid in future. The worst that can happen is that Beta gets nothing. Beta's $10 equity liability means that, on the assumption that Beta is paid the $10 it is owed by Alpha, it will ultimately give that $10 to its owners.

"Alpha also holds $9 in assets, supported by equity." Again, equity doesn't support anything. It is a note in the accounts that the difference between its $19 of assets and its $10 of liabilities is owed to Alpha's owners.

I think the source of confusion is the thinking that led to the (IMO awful) uses and sources of funds model. The underlying assumption is that every economic action is part of a transaction with an equal and opposite transfer of money. So if a Walmart offers a customer a $5 voucher as a goodwill gesture because they didn't like the flavour of some cheese they bought there, that counts as a *source of funds* for Walmart, even though that doesn't make any sense at all. The underlying assumption is that the customer bought a $5 voucher with $5 of cash.

You get the same with equity. Normally, a firm gains equity when its owners transfer money to the firm. It's the money (the asset) which supports the firm, not the equity. Equity represents the fact that the firm owes that money to the owners.

All in all, I think it's really important to keep in mind that there can be individual economic actions (assignment [tangible/debt], issuance, set-off and novation) which are not part of a transaction. They transfer some of one party's (raw) net worth to the other.