Getting back to normalization

The December 2021 FOMC minutes

This week the Fed released the minutes of its December 2021 meeting. The document reflects a discussion of so-called "policy normalization," which is likely to be a dominant theme for the Fed in the coming months. The minutes clarify how the Fed is thinking about its job going forward. Most commentary has thought of the central bank as responding to inflation, but I find that focusing on money markets is more informative.

What is "normal" anyway?

The US has not had normal monetary policy since 2007. So any normalization will have to encompass the task of figuring out just what constitutes "normal." With any luck, we'll recognize it when we get there! Still, at this point the FOMC seems pretty certain on at least a couple of points: the normal fed funds rate is greater than zero, and the normal size of its balance sheet is smaller than it is now. These are the two knobs that the Fed plans to turn as it tries to figure out what is now normal—liftoff (of rates) and runoff (of assets).

The minutes show policymakers refreshing their memory as to what they were doing just before the pandemic. The policy stance was at that time also one of normalization. Importantly, that normalization was not going well even before COVID-19.

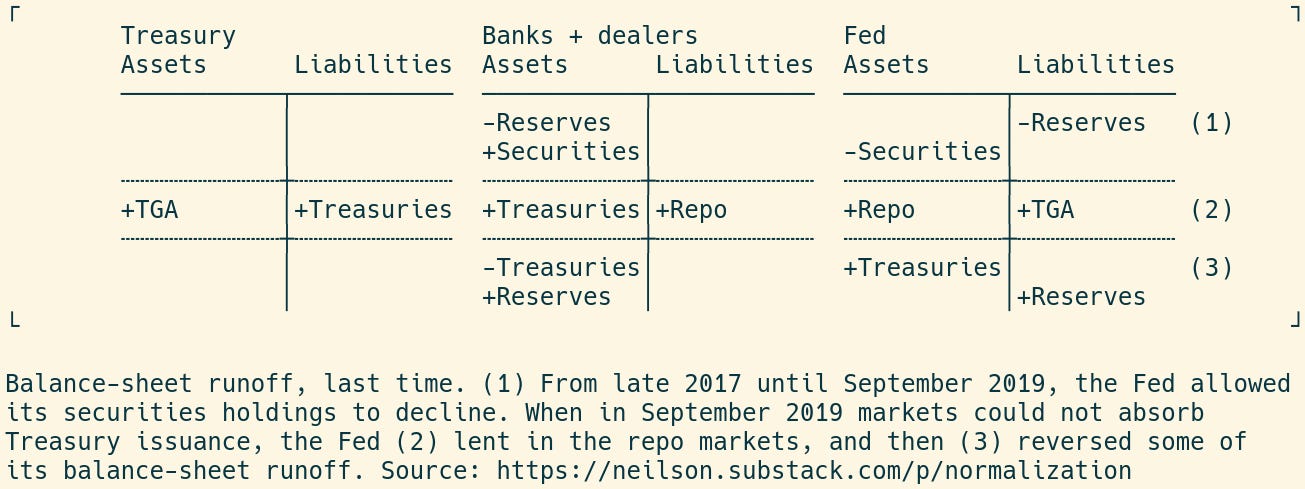

Rates had come off their post-2008 zero by 2016, and were above 1% by the end of 2017. The Fed then began running off assets: it contracted its balance sheet by allowing its Treasury and mortgage-backed securities to mature. Repayment of those securities destroyed reserves. By September 2019, that process reached a breaking point in the repo markets: the Treasury's attempt to issue debt caused repo rates to spike. The Fed responded as a lender of last resort to the repo markets. Between September 2019 and the emergence of the pandemic, the Fed partially reversed the runoff, expanding its Treasury holdings again.

These T accounts summarize the balance-sheet runoff period from late 2017 up to the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic:

This time is different-ish

Much has changed since 2019. The Fed's balance sheet is much larger, and rates are back to zero. But the context is again one of increasing rates, as well as first tapering, then shrinking the balance sheet.

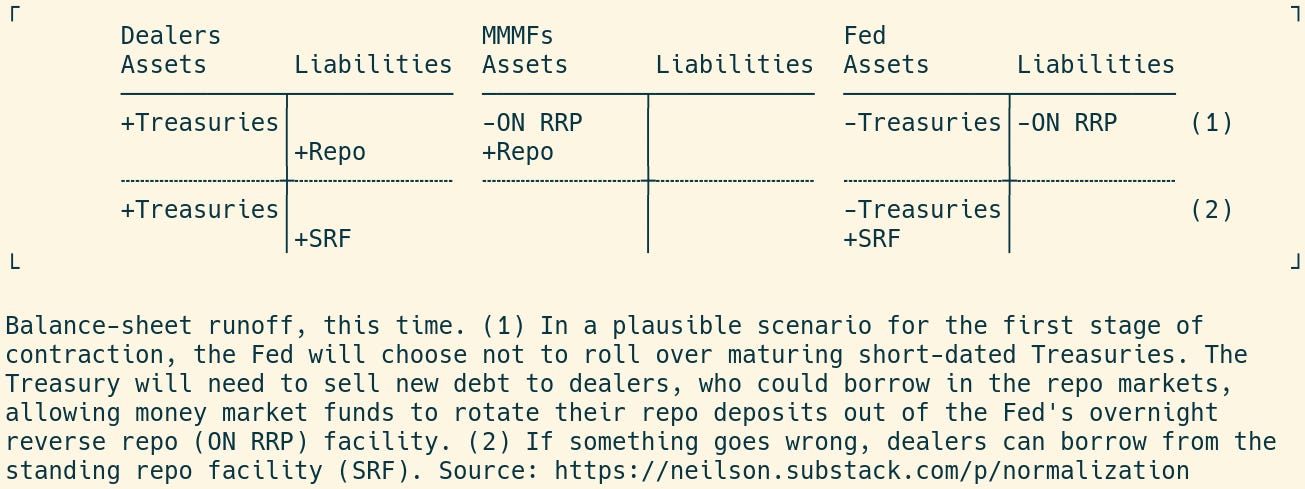

The December 2021 minutes make clear that balance-sheet contraction may come sooner and faster this time around. On the asset side, the central bank's holdings of Treasuries are shorter-dated now than in 2019, so they will run off faster absent a policy to do otherwise. On the liability side, the Fed views the $1.5 trillion balance in the overnight reverse repo (ON RRP) facility as not normal. If these indications do in fact guide the first stages of runoff, it will look like this (omitting the balance sheet for the Treasury):

The FOMC is keen to do this without breaking money markets as in 2019. That time, the Fed had to lend into repo markets on a crisis footing. Now, differently, the Fed has at its disposal the new standing repo facility (SRF), by which dealers (and soon also banks) can borrow cash on their own initiative and without stigma. In the event that repo markets seize up, that is, banks and dealers can obtain funds directly from the Fed. This possibility is shown below the line in the T accounts above. Even if the SRF is not used, the FOMC is taking its existence as a factor supporting quicker runoff.

We'll find out soon enough

The December minutes do not suggest that the FOMC has made a precise decision about the timing either of liftoff or of runoff, and the discussion is set to continue at the January meeting. But they do convey the expectation that balance-sheet runoff will start after interest rate liftoff, but less than two years after. More to come, certainly, in future meetings.

Hi, thank you for the post. I do not understand why repayment of THOSE securities destroys reserves? You write "... allowing its Treasury and mortgage-backed securities to mature. Repayment of those securities destroyed reserves. By September 2019, that process reached a breaking point in the repo markets: the Treasury's attempt to issue debt caused repo rates to spike." Is it that the issuers (banks) repay their MBS by reducing their reserves? And is it that the Treasury repay by reducing its TGA or its reserves, in a manner of speaking? Repo rates spike because T's got depleted in the repo market AND the T tried to issue more T's?

Neilson, when we talk about TS,

........................................Fed...............................................

-Treasuries -TGA

.................................................................................................

when we talk about MBS

..................................Fed...................................................

-MBS -Reserves

..............................................................................................

............................Bank........................................................

-reserves -deposits

...............................................................................................

...........................PD.................................................................

-deposits

.............................................................................................

What do you think?