Stablecoins and payment areas

On-chain and off-chain are two different countries

The stablecoin–central bank digital currency (CBDC) debate is well underway: growing issuance of private money using blockchain technologies, the argument goes, responds to legitimate complaints about existing payment technologies, but poses new systemic risks. Stablecoins, crypto assets intended to behave something like money in that they trade at a fixed price in terms of state-backed money, are one focal point for this argument. Understandably so, because they are liquid money-like liabilities that could become a source of instability.

The answer, some say, is to create new digital assets that address the legitimate complaints about payment systems, but without the systemic risks of stablecoins. Gary Gorton and Jeffrey Y. Zhang want to restrict private money: either stablecoin issuers have to become banks, or they have to be replaced by CBDCs. Martin Wolf more or less agrees. Stephen Cecchetti and Kim Schoenholtz disagree, arguing that CBDCs cause more problems than they solve, and that stablecoin regulation could be left to governments, so central banks should stay out of it.

These interventions all treat stablecoin issuance as private money creation. This is correct as far as it goes, but it doesn't go far enough. Stablecoin issuers do not only create private money, they also make markets between off-chain means of payment and on-chain means of payment. The debate has not yet taken this fact on board.

Stablecoins as a conduit

Let me explain by analogy to national currencies. Imagine two currency areas, home and abroad. Roughly speaking, if someone with home money wants to spend abroad, they will need to first acquire foreign money. This is the role of foreign exchange dealers, who make two-way markets, buying and selling both currencies. Among such dealers, there have always been some who, for one reason or another, want to stabilize the exchange rate. China's central bank pursued just such a policy for many years as part of the country's development strategy. To implement the fixed or stabilized exchange rate, such a dealer offers to buy or sell in unlimited quantities at the price of their choosing.

Blockchain creates a comparable situation, divided not by national borders but by the technology itself. Each blockchain (Bitcoin, Ethereum, EOSIO) creates a separate on-chain currency area, in which payments are recorded on the distributed ledger. Everything else is off-chain. State-issued monies, and promises to deliver them, serve as the means of payment off-chain. Tokens of various kinds serve as the means of payment on-chain. Stablecoin issuers are therefore making a market between the off- and on-chain means of payment. Not only that, but they are trying to do so at a fixed price, as a central bank would. Note that there are also cross-chain stablecoins, like WBTC ("wrapped Bitcoin" on Ethereum), which make a market between one chain and another.

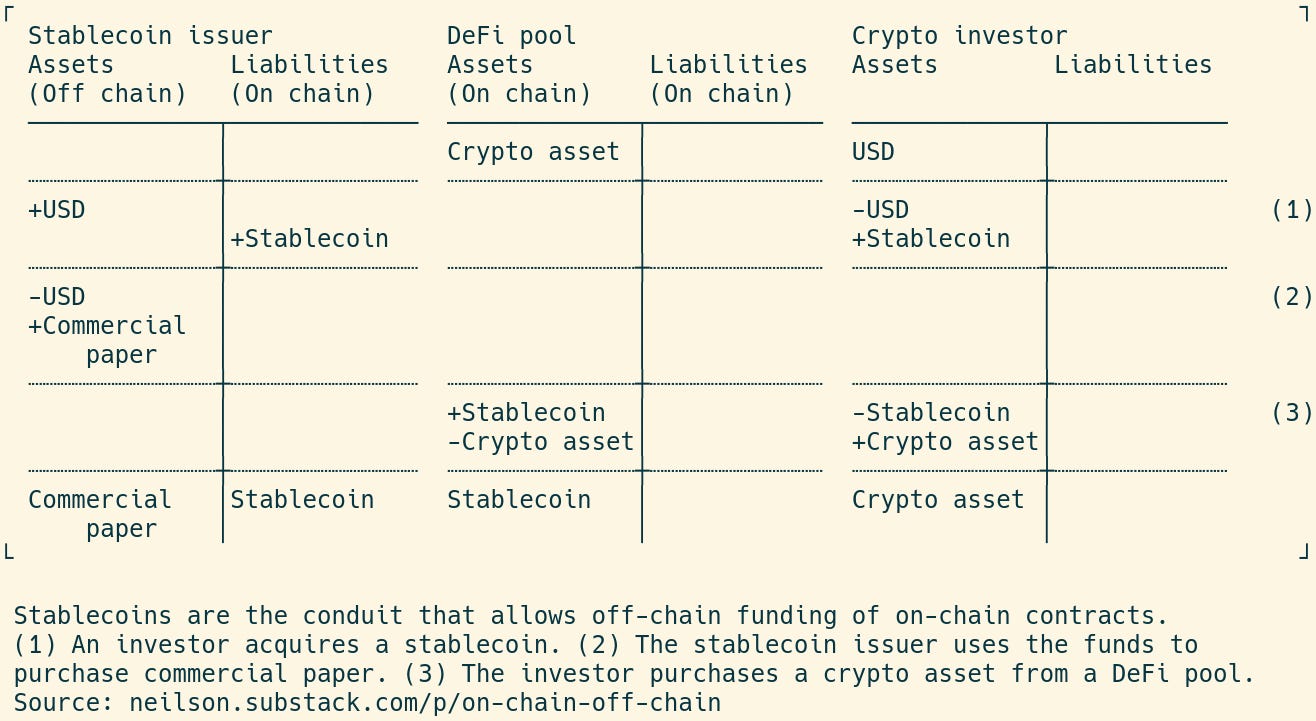

The recent growth of stablecoins has much to do with the growth of decentralized finance (or DeFi as its enthusiasts prefer). DeFi is a network of programmed smart contracts that respond to user transactions according to programmed logic, without discretionary intervention. DeFi is to banking as algorithmic trading is to stock picking, you might say. But DeFi's smart contracts exist only on blockchains, typically Ethereum. In other words: Stablecoins are the conduit that allows off-chain funding of on-chain contracts. Here is an illustration in T accounts:

It is a conceptual mistake to think of on-chain assets circulating alongside off-chain assets, as the private money story has it. In fact they are in two different currency areas. So Gorton and Zhang's conception of stablecoin issuers as wildcat banks, private banks issuing circulating money backed by questionable assets, is misleading. Wildcat banks' liabilities circulated alongside notes issued by other banks; stablecoins circulate in a different payment area, across the border.

The heart of the matter

Central banks have a mandate to stabilize the monetary and financial system. Does that include on-chain contracts? They could regulate stablecoins out of existence, but if DeFi continues to exist, the need for the dealing function will not go away and will be met in some other way. Increasing interest in DeFi from established financial businesses makes it harder to simply shut the whole thing down. Unfortunately for Martin Wolf's argument, CBDCs will not substitute for stablecoins, because they do not provide on-chain means of payment. That all suggests to me that stablecoin issuers will face increasing regulation, but will continue to exist.

But the deeper that on-chain financial interlinkages become, the more serious they are for central banks. The ultimate question, from that point of view, is under what circumstances would central banks buy on-chain assets, or issue on-chain liabilities, to backstop a blockchain liquidity crisis? Right now, the smart answer would be "not under any circumstances."

But let's think carefully: if we don't shut it down, but we also don't provide a backstop, then one day we are going to see what financial instability looks like in a system with no discretionary actors.

Should the DeFi pool have some liabilities in the first row? I would think that they would, akin to the deposits or a claim to whoever placed the crypto asset in the DeFi pool, right? This is fascinating stuff btw