An outside-spread moment

At this point, events have surpassed me. But monetary theory, which is to say the Money View of monetary theory, does offer a way to think about such moments.

Normal market-making

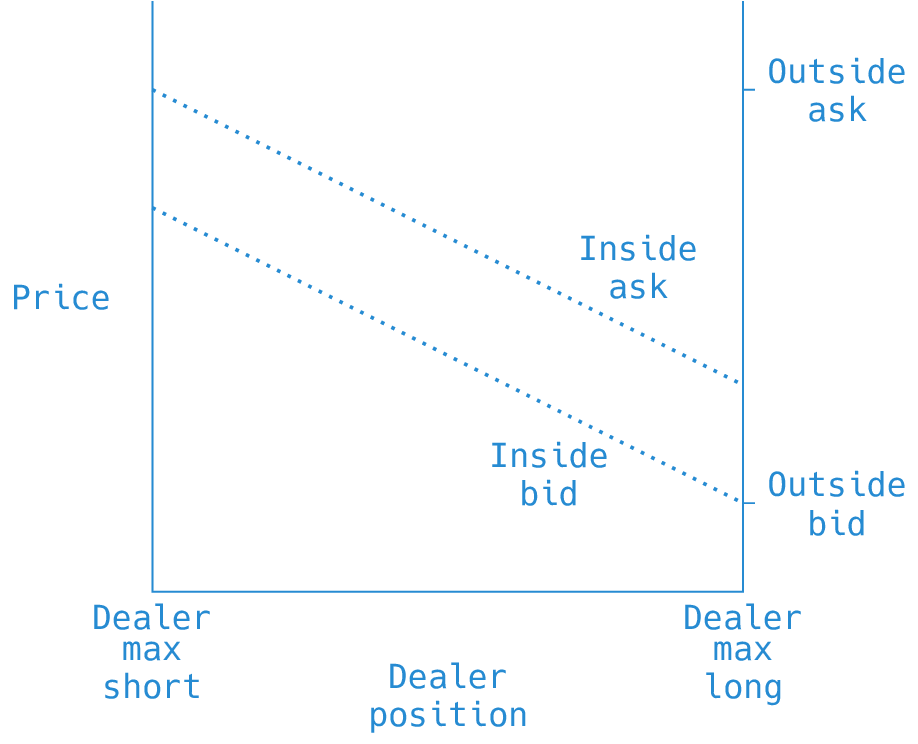

The idea of an outside spread comes from the language of securities dealers, and the easiest way to think about it comes from a disproportionately useful model from a 1987 paper by Jack Treynor. The paper asks a simple question, "How do dealers make markets?" and offers a simple answer, "By buying from those who wish to sell, and selling to those who wish to buy." Intermediating, more succinctly. The only way for a dealer to stay in business, Treynor points out, is to offer better terms than other traders: to buy for more than others are paying, and to sell for less than others are asking. By doing so, the dealer makes an inside spread.

But when dealers either run out of inventory (if they cannot find sellers) or are overrun with inventory (if they cannot find buyers), they go looking for deeper pockets—holders of securities that might sell at a high enough price, or value investors who might buy at a low enough price. Such prices mark the outside spread.

Most markets are not usually at an outside spread—dealers would quickly be out of business if they were. But the day always comes when there is a big one-sided flow, when either buyers or sellers exit the market. On that day, the price falls, hard, until it brings a new buyer into the market; or it rises, sharply, until it brings a new seller into the market.

Outside spreads everywhere

When everyone's understanding of the world changes at once, as in September 2008 or March 2020 or March 2022, many markets go to an outside spread. Prices can move fast in such moments: repo rates in 2008, stock markets in 2020. This week it was commodities prices: nickel trading on the London Metal Exchange was suspended after the price hit $100,000 per metric ton, up from $20,000 a few weeks ago. Or the price of gasoline in the US, a more modest move but one which hits households and businesses very directly:

At the outside spread, new participants come into the market. Just so, the US Department of Energy was working the phones this week, pushing US shale oil producers to expand production, while also scolding their financiers for insisting on profitable operations. Last week, US diplomats were doing their part, making nice with the government of Venezuela, thinking of easing sanctions there in exchange for new oil supplies.

But not necessarily a new monetary order

So we are in an outside-spread moment, and economic arrangements are being redrawn at a dizzying pace. But this doesn't mean, as many have been hasty to proclaim, that a new monetary order is coming. Patterns are changing, to be sure, and too fast to be fully grasped. It is likely that institutions will bend and even break. That is what's it like at the outside spread. But the rules haven't changed, and the center hasn't changed. Yet.

“When everyone's understanding of the world changes at once”

Reminds me of Rebecca Spang’s excellent book about money and the FR, “Money and Stuff in the Time of the French Revolution.” Everyone’s vision of tomorrow changed then too, and outstanding debt called.