The overnight rate complex

Repo and reserves

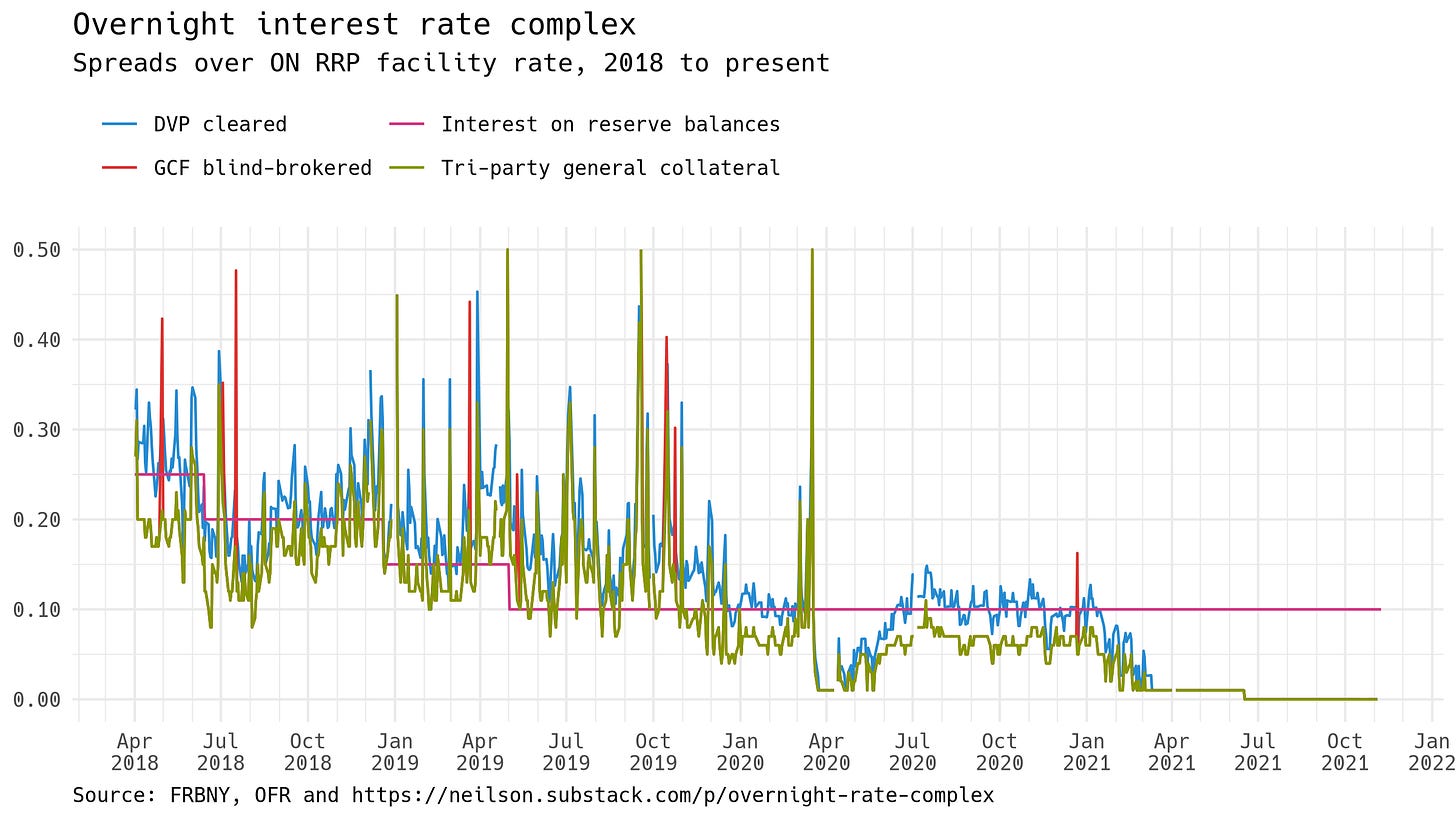

US monetary policy is frequently reduced to quantitative easing on the one hand, and the target for the Fed Funds rate on the other. With a tapering of asset purchases now begun, we are left to speculate as to when rates will rise. But the US central bank interacts closely with a range of short-term interest rates, what Zoltan Pozsar has called the "overnight rate complex." This graph shows some of these overnight interest rates:

In this post, I try to describe the relationship between repo rates and interest on reserves over the last three years or so.

ON RRP facility is a floor

The lowest rate in the graph is the interest paid by the Federal Reserve on deposits in its overnight reverse repo (ON RRP) facility. The ON RRP facility has been particularly important in recent months: the Fed's $4 trillion in asset purchases has surpassed banks' capacity to add reserves, and money market funds have been the marginal destination for those funds. The ON RRP facility predates the pandemic, however, and will continue to exist for the foreseeable future. The graph above shows that the ON RRP facility rate has functioned as a floor for the overnight interest rate complex. No money market fund will lend, and no repo dealer can borrow, below that rate.

Taking the ON RRP facility rate as a floor, we can think of each of the other rates in the overnight rate complex as a spread above that floor. This graph shows the same rates as in the previous, measured as a spread above the ON RRP facility rate.

What are these rates? The tri-party, GCF, and DVP are repo rates, measures of the cost of overnight secured financing against Treasury collateral. The tri-party rate is typically available to money fund depositors. The GCF blind-brokered and DVP cleared repo services are available to FICC members, including banks and security dealers. The magenta line is not a repo rate—it shows the interest rate paid by the Fed to commercial banks on reserve balances.

Zoltan argues that there is a hierarchy of repo rates. To my eye, that hierarchy is visible in the pattern of spreads, although using data from the Office of Financial Research, I cannot distinguish as many different rates as Zoltan does. Still, it is clear that the ON RRP facility is the lowest repo rate, then tri-party above that, then DVP. GCF is a bit harder to fit into the pattern.

Interest on reserves

Comparing the second graph to the first, we can see that the Fed has been narrowing the spread between the interest rate on reserves (IORB rate) and the ON RRP rate. This has happened alongside changes in the levels of interest rates, and so it is not immediately visible in the first graph. But measured as a spread over ON RRP, the steps downward are clearly visible.

The minutes of the FOMC meetings, for example from May 2018, suggest that over this period the central bank was struggling to control the overnight rate complex: high dealer inventories of Treasuries would drive repo rates up, pulling the entire overnight rate complex up as well. This phenomenon reached its peak in September 2019, when repo rates spiked several percentage points. (Note that in the second graph I have cut this spike off.)

The Fed repeatedly narrowed the spread of the interest rate on reserves relative to the ON RRP rate, down to 10 bp from May 2019 to the present. The spread has remained at this level through the COVID-19 pandemic. Repo rates were high, close to the IORB rate, until March 2021, and low, stuck to the ON RRP rate, since then.

It would be nice, analytically, if the IORB rate were either a ceiling or a floor to other rates. But this does not seem to be the case. Instead it seems that interest on reserves represents one among a number of factors, including dealers' needs for repo funding and the overall level of reserves. For this reason, the idea of an overnight rate complex seems helpful: a set of rates that broadly move together, but which also have changing and important internal patterns.

《No money market fund will lend, and no repo dealer can borrow, below that rate.》

Why ignore specials? Is it because the existence of specials threatens the mainstream economic narrative that prices are efficient?

《the idea of an overnight rate complex seems helpful: a set of rates that broadly move together, but which also have changing and important internal patterns.》

Would Fischer Black call this noise?

Don't they trim means and otherwise manipulate the data to report numbers that have purely reflexive value (i.e., if everyone believes in them, they become real by a sort of mass hysterical self-fulfilling prophecy channel)?

Why not report the standard error on their rate surveys? Are the confidence intervals too wide to say any one story is more likely than any other (back to noise)?