The PBOC balance sheet

Part 2: Banks' foreign assets

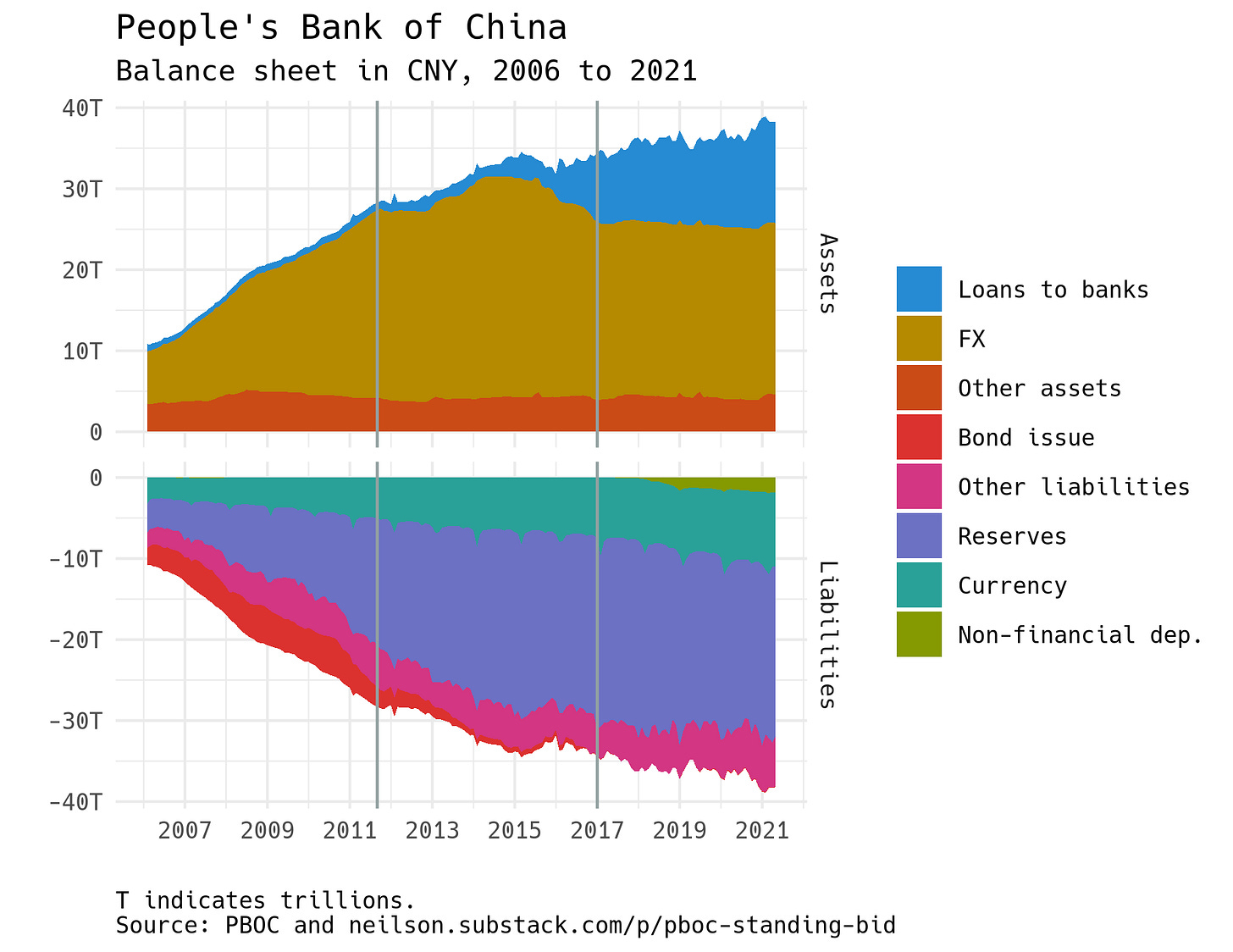

This is the second part of my analysis of the PBOC balance sheet. In the first part, I started from this graph of China's central bank's financial position over time:

The period up to the first vertical line, in the second half of 2011, represents the PBOC "standing bid"—an open-ended willingness to buy—dollars entering the country. The period after the second line, from 2017, is the focus of this post. But first, readers called my attention to a loose end from last time.

I have focused on current-account transactions, exports, as the source of FX accumulation, but said nothing about investment inflows, which were also large. It is certainly true that significant volumes of dollars entered China via FDI during this period. What happened to those dollars? Possibilities are three: 1) they were used to purchase inputs abroad, in which case there was no net reserve accumulation; 2) the investments were later paid back, in which case there was also no net reserve accumulation; 3) the dollars were exchanged for yuan and spent domestically.

In this third case, the dollars would have been sold, no different from current-account inflows, and would indeed end up as FX reserves at the central bank. As long as, on net, the pool of accumulated FDI continues to grow, then the "standing bid" analysis still applies, and what is being exported is ownership claims on Chinese production.

I'll leave that aside for now, but let me say once more that I am trying to look through the central bank's balance sheet and get a macro window onto the entire Chinese financial system, which is sure to be incomplete. If readers know of different analyses, or have their own, please get in touch.

After 2017: Foreign assets in the banking system

Beginning in mid-2011, a series of changes brought about new pattern for the PBOC, which by 2017 had settled into the balance-sheet structure that is in operation today.

The differences are visible in the graph above: the PBOC continues to expand its portfolio, but no longer by buying foreign exchange. Instead, the expansion comes in the form of increased lending to the country's banking system. This has been funded, on the liability side, by issuance of currency and reserves, and more recently with a small but growing expansion of deposits to non-financial institutions. (Also notable is the increased month-to-month variability of the total size of the balance sheet: an important question for a future edition of Soon Parted.)

Dollars continue to flow into the country: China recorded a current-account surplus of 487 billion CNY (75.1 billion USD) in the first quarter of 2021, mostly invoiced in foreign currency. Under the standing bid FX regime through 2011, the PBOC was buying a lot of those dollars, but since 2017 that is no longer the case. So what balance sheet in China is holding the continued FX inflow?

Several clues suggest the answer. This April speech points to an accumulation of foreign assets by the private sector, totaling 5.3 trillion USD at the end of 2020. In a surprise move earlier this month, the PBOC increased reserve requirements on FX deposits. And the renminbi has been been on an upswing (one yuan buys more dollars; one dollar buys fewer yuan) since the beginning of the pandemic.

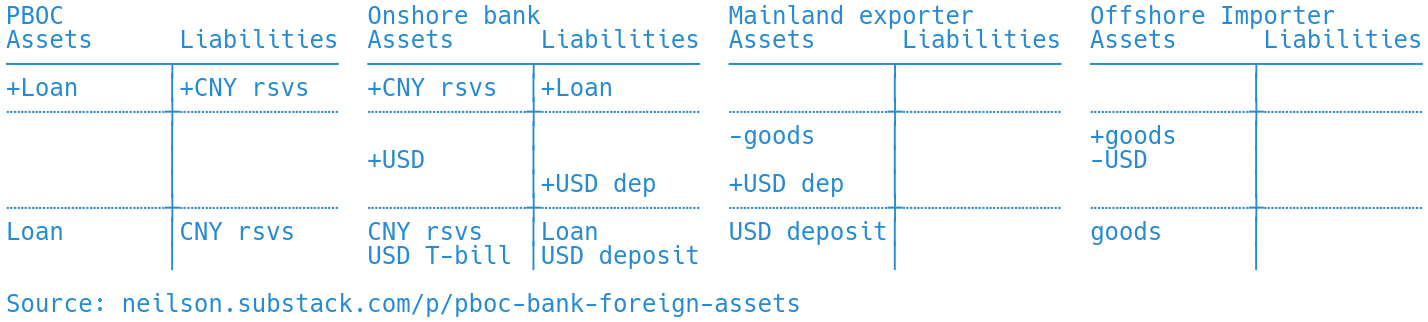

It seems that the commercial banks are holding the incoming foreign exchange. Banks face a reserve requirement as they expand their foreign-exchange deposits, and we can see from the graph above that the marginal supply of those reserves comes from PBOC lending to the banking system. The PBOC is issuing reserves, and lending the funds back into the banking system, presumably at longer term. In T accounts:

FX reserve accumulation is still happening in the broader state financial sector, but through a clear shift in policy, it is happening on the balance sheets other than that of the central bank. Exchange risk is now being housed on banks' balance sheets rather than the PBOC's.

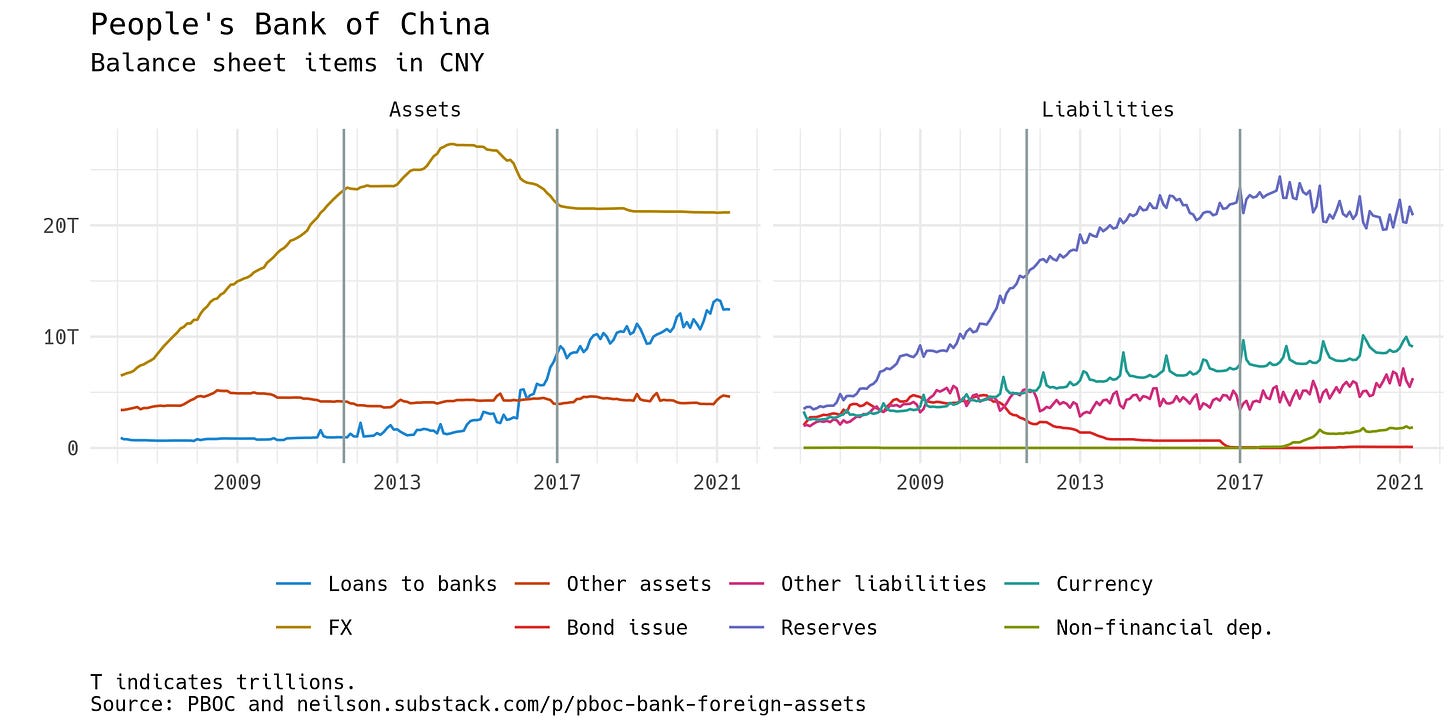

Key to this system are the PBOC's loans to banks, which in the post-2017 system provide both the secular expansion and the month-to-month fluctuation in reserves. In my still-imperfect understanding, PBOC loans to banks come in the form of liquidity facilities, which are accessed on the initiative of the banks. This graph, which uses the same data as above but unstacks the balance-sheet entries, makes it easier to see how this works:

Loans to banks, the blue line on the asset side, is the only asset entry with significant month-to-month fluctuations. On the liability side, these are balanced by seasonal fluctuations in currency issue, and monthly variation in reserves and government deposits (under other liabilities).

That's all for now

There are other big shifts going on in China's financial system—the rollout of a central bank digital currency, the domestic crackdown on crypto mining and transactions, regulation of fintech companies, and a number of recent ventures by global banks setting up shop in the country. The PBOC's balance sheet is one place where all of these come together.