Quantitative tightening and overnight rates

When the leaders speak of peace

The common folk know

That war is coming

When the leaders curse war

The mobilization order is already written out.

─Bertolt BrechtWhen the Fed begins shrinking its balance sheet, quantitative tightening (QT) will follow a daily cycle of transactions that will leave the Fed's balance sheet smaller each day. In a previous post, I outlined (and even animated) these daily mechanics. That analysis focused on the daily churn of US Treasury issuance, and assumed that dealers would be able to sell Treasury securities on to their customers. Today, again following Zoltan Pozsar, I look at what happens if the securities instead pile up on the dealers' balance sheets, and what that might mean for the overnight rate complex.

Which liabilities will contract?

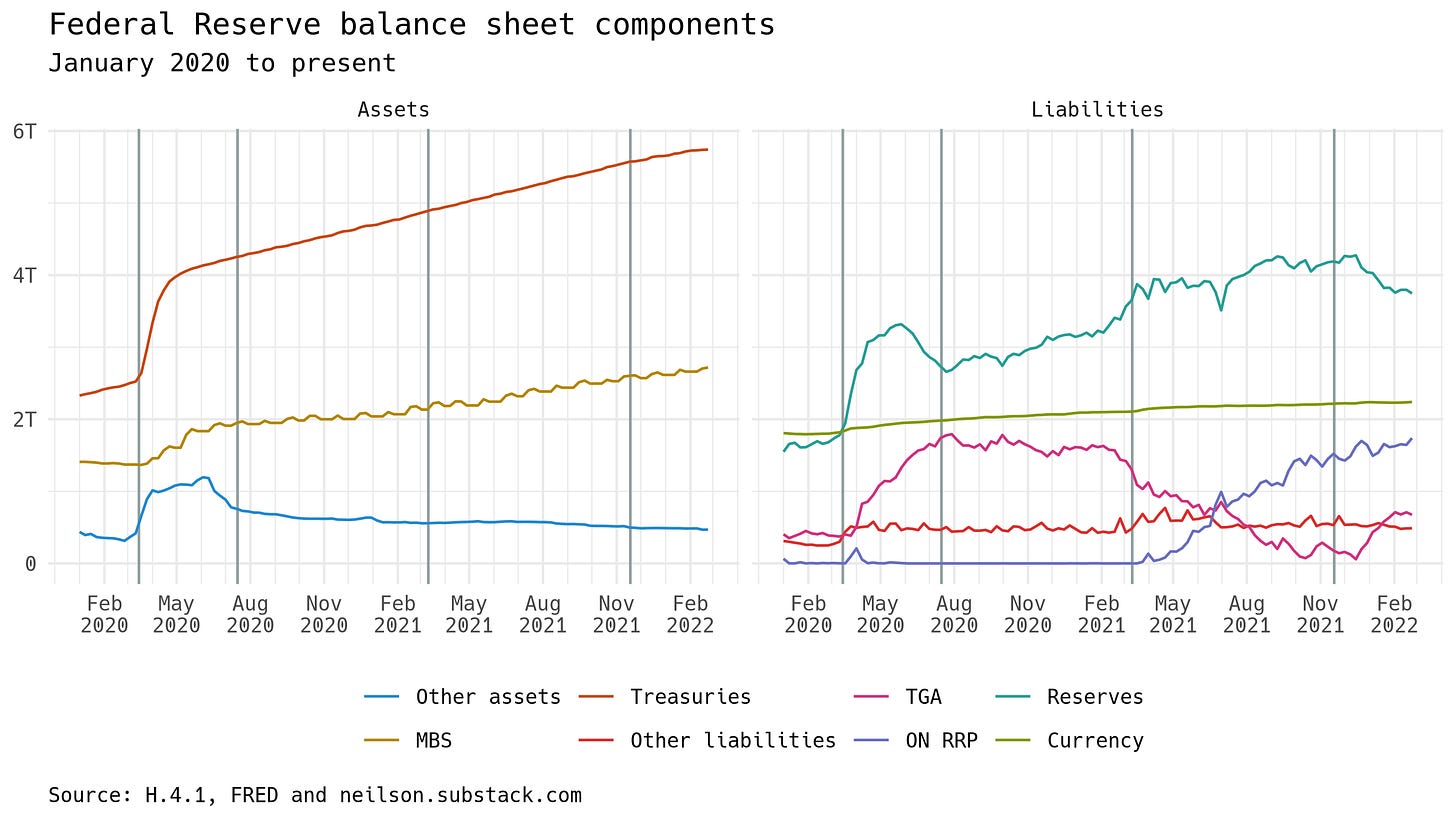

The Fed expanded its asset holdings during the pandemic, from March 2020 to present, purchasing Treasury and mortgage-backed securities. This expansion was funded on the liability side by an increase in reserves—deposits by the commercial banks—and an increase in the overnight reverse repo (ON RRP) facility—repo deposits by money market mutual funds.

This graph shows the main entries on the balance sheet of the Fed. It is easy to see from the shape of the lines that the levels of assets, to the left, are variables set according to policy; the levels of liabilities, to the right, are the outcomes of a process over which the central bank has less control:

The Fed is planning to allow its balance sheet to contract, beginning at some point after overnight interest rates been raised above zero, perhaps around mid-year. It can do this by choosing not to reinvest the proceeds of its bond holdings as they mature. Total liabilities will contract, but which ones?

Who will buy Treasury debt?

The answer to this question depends on who will buy the US Treasury's newly issued debt once the Fed stops reinvesting. It is possible that these securities will go straight to permanent homes on deep balance sheets, what Zoltan calls "beautiful QT." Here, I want to follow the uglier possibility, that new Treasury securities will instead get stuck in short-term security dealer inventories.

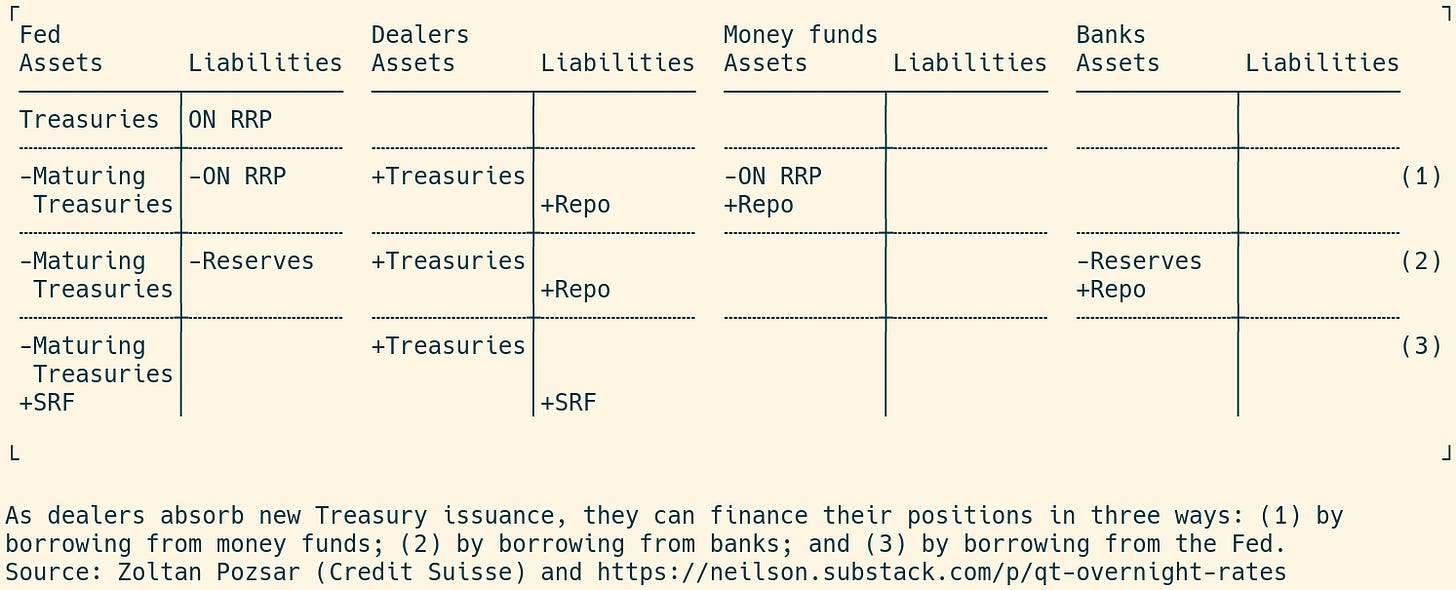

Because dealers operate on slim capital, they will have to finance these inventories by increasing their borrowing in the overnight repo market. As these financed inventories grow, the market repo rate will be bid up from its current position, floored at the rate the Fed pays on ON RRP deposits. Money funds will reduce their deposits in the facility and lend instead to dealers, shown in row (1) below.

When the ON RRP facility is exhausted, the next pool of funds will come from banks, shown in row (2). Banks have the option of depositing reserves at the Fed at the IORB rate, so the repo rate will have to cross above IORB around this same time.

As QT continues past this point, dealers' inventories will continue to grow and the repo rate will continue to rise. But there is a limit, because the Fed has its new Standing Repo Facility. If repo rates rise to what the Fed charges at the SRF, dealers will activate the facility, shown in row (3) below:

The SRF prevents repo rates from rising any further. When activated, usage of the facility shows up as an asset on the Fed's balance sheet. In other words, activation of the SRF short-circuits QT, stopping the Fed's balance sheet from contracting. In fact, dealers would post their excess Treasury inventories back to the Fed overnight as repo collateral, undoing QT at least overnight.

New normalization

The Fed is trying to avoid a repeat of September 2019, when its last attempt at balance-sheet contraction coincided with difficult financing conditions for Treasuries, and repo rates spiked. This time around, the Fed will have a way to know if it has pushed QT too far.

Once QT comes up against the SRF, can the Fed just increase the SRF rate to be able to continue on with QT?