Sources and uses

A quiet plea for better accounting

Readers of Soon Parted do not, in general, need to be convinced that clear accounting is a helpful addition to economic reasoning. My T accounts usually show balance sheets, which capture changes in assets and liabilities. Because I am most often writing about financial and monetary issues, I believe this gets the point across in the most transparent way.

But not all transactions go on the balance sheet. For some questions, it is helpful to have a way of accounting for income flows and balance sheet transactions together. For this, T accounts based on sources of funds and uses of funds can be clearer than balance sheets. This post uses a familiar example to illustrate sources and uses accounting, then applies it to clarify two key ideas from macro- and international economics.

Inside money

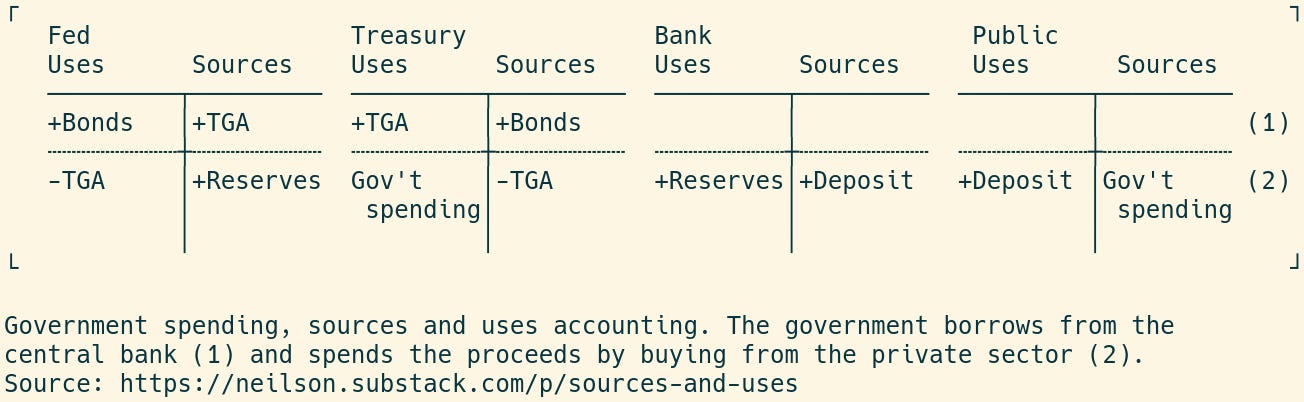

Start with a monetary example, one likely to be familiar to Soon Parted readers. These four balance sheets show how a government can borrow from its central bank and then spend the money by purchasing from the private sector. The proceeds of the government's borrowing come in the form of a deposit account at the central bank. In the US, this account is called the Treasury General Account or TGA. When the government spends those funds, it initiates a transfer at the central bank, which completes the payment by reducing the TGA balance and increasing the reserve balance of the recipients's bank. The bank receives the reserves and increases the payee's deposits accordingly.

Balance sheets show changes in stock variables: liabilities and assets are promises (made or accepted) regarding future payments. I show the accumulated amounts as the last line in the T accounts. What asset does the government get in exchange for its spending? I think of the Treasury as acquiring an equity claim on the public as a result of this transaction. The Treasury will eventually collect on that claim by taxing the public.

Here is a way to look at the same two transactions using a different accounting framework. The following T accounts are not balance sheets. Instead they are statements of sources and uses of funds. Unlike balance sheets, these sources and uses accounts are focused on the flows, not on the accumulation. That creates the flexibility to combine income flows with asset transactions, so we can just think of the government as spending, rather than having to make an argument about an abstract equity claim:

The first line looks the same. But the entries on the second line are arranged differently. For example, in the balance-sheet perspective, the TGA is always on the left side for the Treasury, because it is an asset. But in the sources and uses perspective, running down the TGA balance is a source of funds for the Treasury, so it appears on the right side. The opposite is true for the TGA entry on the Fed's balance sheet. Any balance sheet transaction can be written in this form—it can be helpful to do so when you want to combine it with income flows.

Balance of payments

Sources and uses accounting often makes it easier to understand economic arguments. It can be more transparent than writing income identities as equations, once you get used to double-entry accounting. For example, here is a simple accounting framework for international transactions:

In this layout, there are two regions, home and everywhere else. For each region, cross-border transactions are categorized as either trade flows (imports or exports) or capital flows (outflows, which are lending, or inflows, which are borrowing). With only two regions, imports on one side correspond to exports on the other side, and likewise for capital flows.

In international economics, it is common to net out exports against imports, and capital outflows against capital inflows. For example, if the home region imports more than it exports, then it has a net deficit in payments on its current (trade) account. Because there are only two regions, this means that the rest of the world has a surplus of payments on current account. Because total sources equal total uses for each region, this also requires home to show a surplus of payments on capital account, and the rest of the world to show a deficit of payments on capital account:

But reasoning based on net flows is not always helpful. On the trade account, a region might face different circumstances for its imports and its exports, which the net trade balance obscures. Capital flows might include longer-term asset transactions as well as short-term monetary flows. Depending on the question being asked, it may or may not be correct to net them out.

Investment and savings

If the perspective of international economics is frustrating, that of macroeconomics is doubly so. Macro discourse frequently treats financial flows very reductively, which obscures what I consider to be the important issues. Even so, clear accounting is our best shot at having a conversation. Here is a minimal two-sector national income macro framework with sources and uses accounting:

These sources and uses T accounts say that households earn income, spend some on consumption and save the rest. (That is the definition of savings S=Y-C.) Income comes from the business sector (i.e. as wages), and consumption goods are purchased from the business sector. Business sells consumption and investment goods and pays factor income to households. (That is the GDP identity Y=C+I.) If you are used to thinking about money and finance, beware! This is different. This GDP framework uses only flows: no accumulation is being accounted for here. It uses only real flows: it describes a world of barter, though we nonetheless manage to measure everything in money amounts.

Sources and uses balance for each sector, so the total of all sources, across sectors, and the total of all uses also balances. National product equals national income, so macroeconomics proudly announces that "investment equals savings," which is in fact a consequence of the way the accounting framework defines investment and savings. But then, some people do the saving and other people do the investment, so what makes them equal? In the real world, both savings and investment go through the financial system, which has no place in national income accounting. In the real world, financial flows involve a lot of asset accumulation, creation and destruction, which also has no place in macro accounting. And in the real world, all of these transactions are mediated by monetary flows, which again has no place.

(I would be remiss if I did not mention the stock–flow consistent approach to macro modeling, which tries to address precisely these issues.)

A quiet plea

Both international economics and macroeconomics reduce everything to fit into narrow accounting frameworks, and both tend to eliminate financial and monetary flows entirely. As a consequence, those frameworks are much less helpful than they could be. Sources and uses accounting cannot, by itself, correct those theoretical shortcomings, but I do think it could help improve the conversation.