Regulating crypto

Reading the Stablecoin Report

Last week the US Treasury published its report on stablecoins, signed by the President's Working Group on Financial Markets, the FDIC, and the Comptroller of the Currency. (The latter two are US bank regulators.) Coming on the heels of the regulatory framework proposed by the BIS and IOSCO, the document is a big step by US authorities toward reining in the crypto world. The Stablecoin Report, below the surface but not too far below, is based on a balance-sheet view. In what follows, I make that balance-sheet view explicit and use it to interpret the risks and recommendations that the report identifies. I'll follow up next time with a look at what the report says about DeFi specifically.

Financial structure

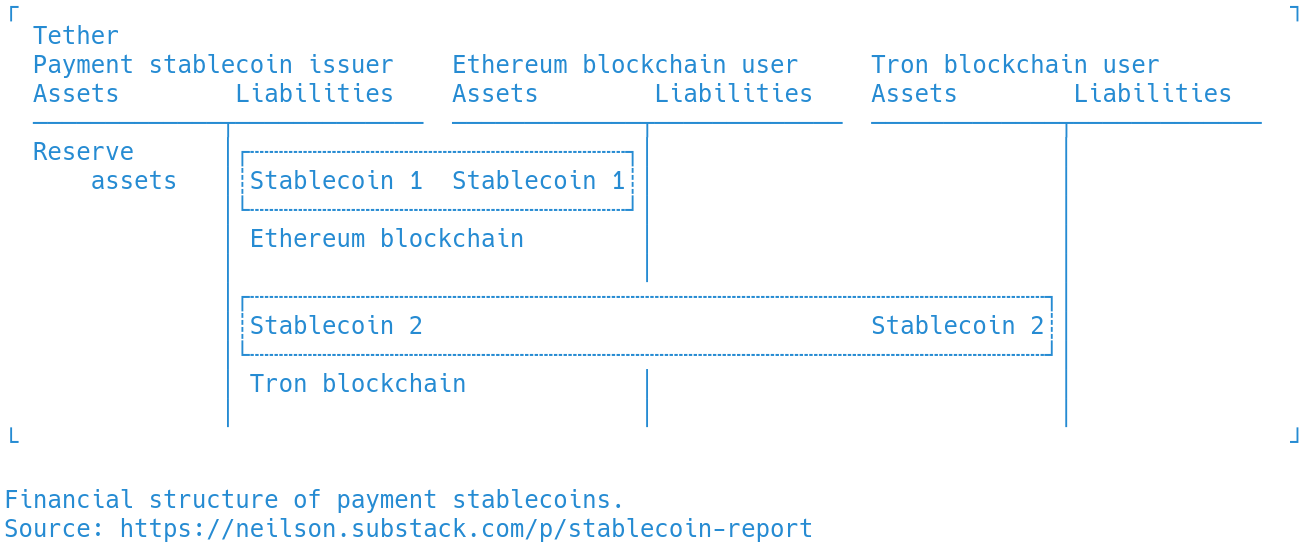

The Stablecoin Report is based on an understanding of the financial system as a network of interlocking balance sheets. Each balance sheet corresponds to a legal entity—a person or a business. In the network, the balance sheets of different entities are connected by financial claims. T accounts like those below are one way to represent this two-sided structure. This particular example shows the financial relationships between Tether, a stablecoin issuer, and two stablecoin users. Tether issues stablecoins and purchases reserve assets with the funds generated by that issuance. The choice of reserve assets varies among issuers; in Tether's case it is mostly commercial paper.

On the liability side, I show Tether as issuing two different stablecoins, one on the Ethereum blockchain and one on the Tron blockchain. A stablecoin transaction, like any transfer of crypto, is recorded as an entry in a public ledger. The various blockchains are distinct from one another, and a given stablecoin is on one and only one blockchain. Tether, for example, issues liabilities on several blockchains, but each should be thought of as a distinct stablecoin. The majority of Tether's stablecoins outstanding are on the Ethereum and Tron chains, as I have shown in the T accounts above. These liabilities, in turn, are held as assets by users of each blockchain. For the users, the stablecoins are meant to be easily transferred as payment, and easily redeemed for dollars. The report calls these "payment stablecoins."

This balance-sheet structure makes it easy to state the report's conclusions. Payment stablecoin issuers have moneylike liabilities, and so (the report says) they are banks. The first recommendation is that stablecoin issuers become regulated banks. If stablecoins serve a banking function, then depositors should get the protections that they would get at a bank, and the simplest way is that stablecoin issuers should become banks.

If they do become regulated banks, then stablecoin issuers will become subject to constraints on the structure of their balance sheets. For example, regulators will be concerned that the value of reserve assets be greater than the value of the stablecoins that have been issued. They will also want to see the details of this calculation, rather than accept a private attestation, as some issuers have done up to now. Regulators will also want to know what other liabilities stablecoin issuers might have (loans, for example), and in what order these would get repaid in the event that an issuer failed. They would also want to know that the assets could be readily sold for cash in case a lot of users wanted to redeem their stablecoins at the same time.

Wallet services

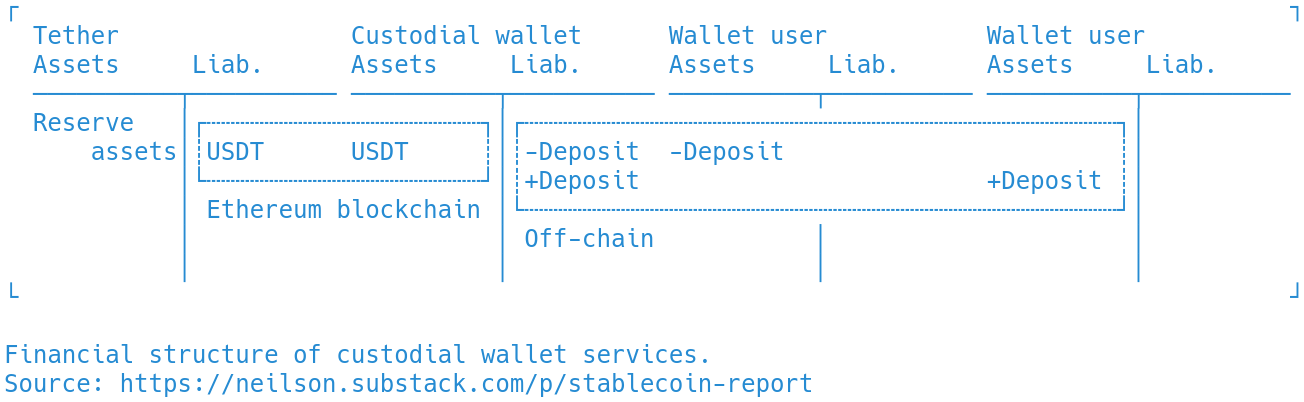

So much for the balance sheets of stablecoin issuers. The Stablecoin Report also focuses on multiple sources of so-called payment system risk. One source is in the provision of custodial wallet services. Custodial wallets allow users to transact without holding crypto assets directly. Instead, the wallet provider owns the crypto assets, and users hold what amounts to a deposit claim. When wallet users transact among themselves, the wallet provider completes the transaction on its own books, without any blockchain transaction. The following T accounts illustrate the financial relationships:

The report notes this structure, and points out that custodial wallet providers too are providing a banking service. It argues for oversight of wallet providers, and restrictions on their ability to lend. A custodial wallet provider, that is, must actually have the crypto assets that it claims to hold in custody. Again, regulators will want to verify this in some detail.

Blockchain

There is an alternative to custodial wallets: users can hold on-chain assets directly, as in the first T accounts above, and as the wallet provider itself does in the second set of T accounts. Anyone can do this on a public blockchain like Bitcoin, Ethereum or Tron. The technical know-how required is not enormous, but as the report notes, many users still choose custodial arrangements. Even so, on-chain transactions are subject to a second source, or set of sources, of payment system risk. These have to do with the operation of the blockchain algorithms themselves.

For example, a blockchain transaction is not complete until it is recorded in the shared ledger, a state known as consensus, achieved through a process known as mining. It may happen that, at a given moment, not enough computing resources are devoted to mining, and a transaction fails to clear or clears very slowly, sometimes called network congestion. This raises a related issue. Even under normal conditions, the transaction validation process leaves settlement ambiguous—it's hard to tell who owns what when. Similarly, if settlement is slow, it is difficult to say who is responsible for the delay. Regulators, the report makes clear, will not let these questions remain unanswered.

Versions of this issue are raised several times in the Stablecoin Report, and to my thinking this is the point with the biggest implications for the future of crypto. The report compares blockchain designs to existing payment infrastructure. The existing system, it observes, handles $100 trillion in payments a year, 600 million transactions a day, and has clear lines of responsibility and accountability. Public blockchains, by contrast, are slow, use a lot of energy, and offer no entry point for regulation.

But the report also offers a way forward: "[P]ermissioned blockchains may offer more certainty as to who is responsible for monitoring the network and complying with the rules of the network. Depending on design, however, they may offer less transparency and security." That seems to be a directive to the existing banking system to build their own blockchain that is designed to be transparent and secure, to regulators' satisfaction. If that is indeed what comes to pass, it will represent a quite thorough absorption of crypto innovation into the existing banking system.