Stablecoins and DeFi

Banking for unattended contracts

Last week the Bank for International Settlements and the International Organization of Securities Commissions proposed a regulatory approach for stablecoins. Their report starts from the perspective that stablecoins are financial market infrastructure, and so should be regulated like payment systems and clearinghouses.

Stablecoins are hard to categorize. As with many crypto innovations, they combine technological features with monetary features, and so may appear different to different observers. This post argues that stablecoins are increasing in importance because of the rapid development of unattended contracts. These decentralized financial agreements are expressed in computer code, executed without human intervention and make use of potentially complex interdependencies and conditional logic. It may be hard to make stablecoins safe without understanding what instability could emerge from the decentralization of finance.

Stablecoins as crypto deposits

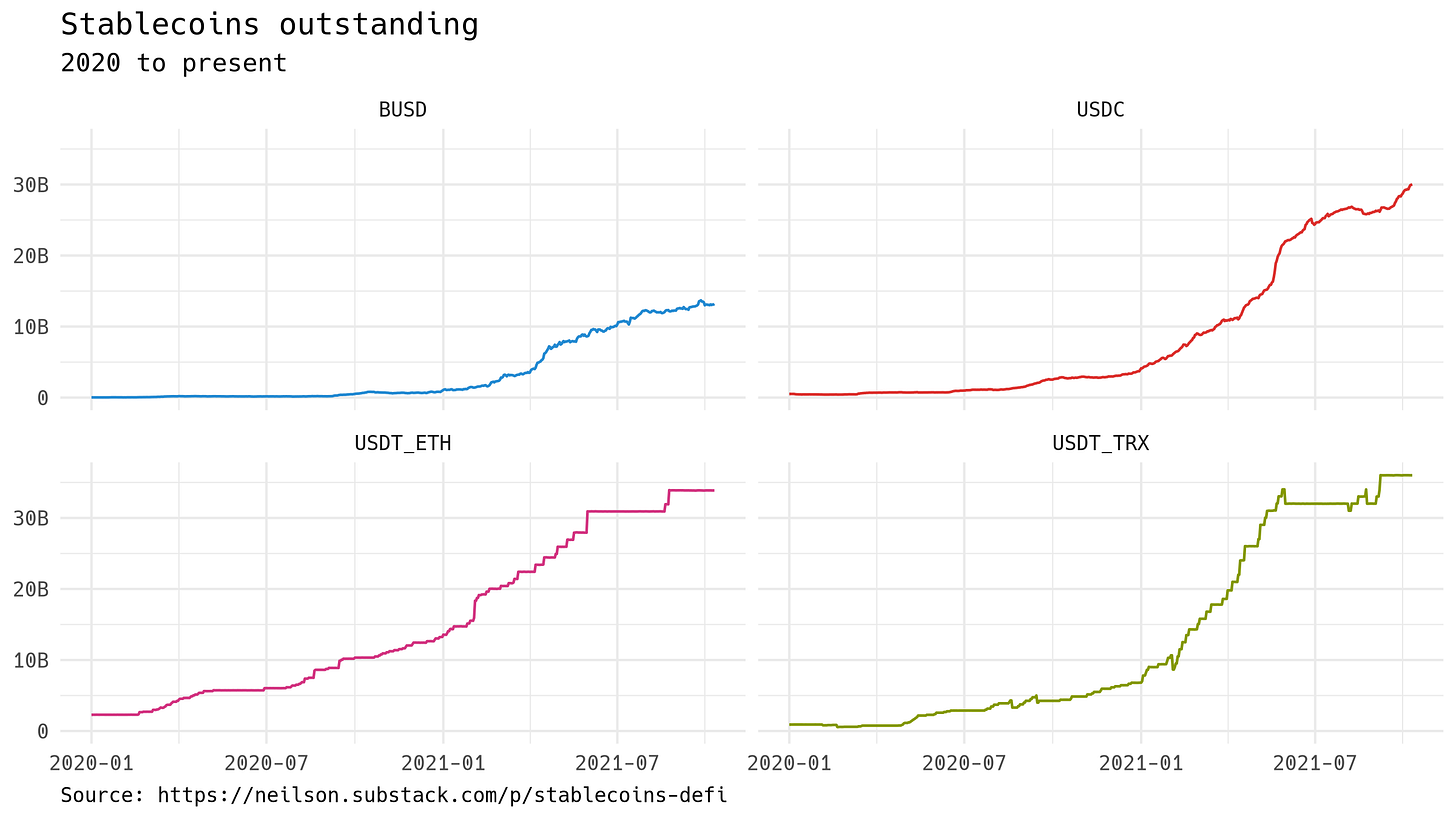

This graph shows the total outstanding issuance of the four largest stablecoins. Two of the four are issued by Tether, on the Ethereum and the Tron blockchains. USDC is jointly operated by Coinbase and Circle, on the Ethereum blockchain; BUSD by Paxos, on the Binance Smart Chain. Issuance of stablecoins has risen steeply from next to nothing at the beginning of 2020 to more than $100 billion at present.

Stablecoins are frequently regarded as digital assets whose main purpose is to serve as a vehicle for electronic payments. Such a view takes stablecoins as somethling like bank deposits, and their issuers as something like banks. Like banks, stablecoin issuers have liquid liabilities (the stablecoins themselves) and less liquid assets (typically commercial paper). They are therefore bearing liquidity risk, the possibility that the obligation to redeem liabilities will require them to liquidate assets at a loss. In the extreme, those losses could fall back onto stablecoin holders, who have no expectation that their funds are at risk, and who have no recourse to any kind of deposit insurance.

Stablecoin issuers' asset holdings also create a more systemic concern, expressed for example in this note accompanying a review by Fitch, that a sudden rush to redeem stablecoins would force issuers to sell their commercial paper holdings, leading to a disruption in that markets. Tether, the largest issuer, now numbers among the world's top holders of commercial paper, so the risk of contagion does seem well founded.

Stablecoins as DeFi conduit

It is, however, a bit hard to makes sense of the rise of stablecoins by viewing them only as an electronic means of payment, and viewing issuers only as banks. The ease of on-chain payments using stablecoins does not make up for the complexity of having to move funds on chain in the first place. I have previously argued that an understanding of stablecoins needs to take account of the economic function they serve—namely, to create a conduit between off-chain sources of funds and on-chain uses of funds.

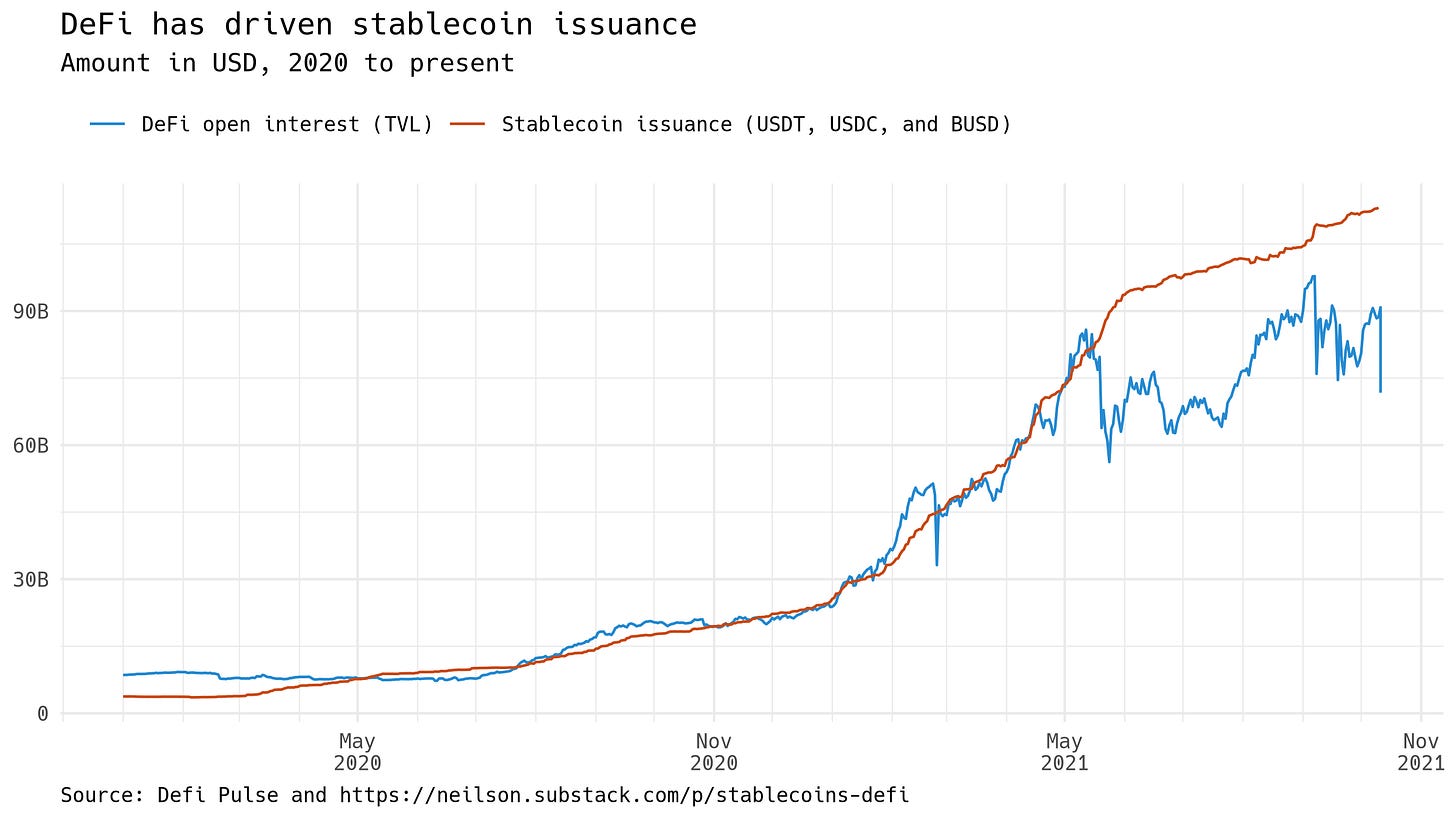

This graph shows, in red, total stablecoin issuance for the same top stablecoins as above, and in blue, the outstanding open interest in decentralized finance (DeFi) unattended contracts. The DeFi data comes from DeFi Pulse, where in keeping with the lingo it is known as "total value locked." I call it open interest by analogy to futures markets. Given the rapidly changing nature of the phenomenon, we should be cautious in drawing conclusions. Even so, it seems clear that the growth of stablecoin usage, and the growth of decentralized finance, are closely connected.

This connection is stablecoins' infrastructural function: to enable participation in DeFi unattended contracts, a speculator must first bring value on-chain. Stablecoins have become the preferred way to do that, because par clearing simplifies the analysis of transactions and the comparison of alternative investments. These considerations are familiar banking ideas. But unattended contracts (which may or may not prove to be "smart") are in many ways genuinely new. Importantly, they are what is driving the use of stablecoins.

Regulating stablecoins

The difficulty in designing a regulatory framework for stablecoins, it seems to me, is that issuers are providing liquid liabilities to be used in discretionless, automated transactions that could become quite complex. They have familiar bank-like balance sheet structure, but that may not prove to be a good guide to possibilities for instability arising from decentralized finance. In any case, thinking of stablecoins simply as unlicensed banks seems likely to miss the point.

I don't mention SCs specifically but I've discussed systemic risk mitigation in DeFi with special reference to insurance here (in case of interest): https://twitter.com/mlphresearch/status/1372154033314656259

Dear Neilson; TVL and stablecoin amount, I dont understand this relationship