The 2008 crisis, part 2

Bear to Lehman

This is the second part of a short financial history of the 2008 financial crisis. The introduction and first part are here. Part 3 is here. All of the crisis facilities are depicted as animated gifs here.

The Fed steps in

Until early 2008, private markets were able to absorb the exit from positions in mortgage-backed securities, though not without big movements in prices. In March of that year, however, investment bank Bear Stearns collapsed and was sold to rival JPMorgan Chase. This institutional failure marked a turning point, after which the Fed’s balance sheet was deployed to quell the panic.

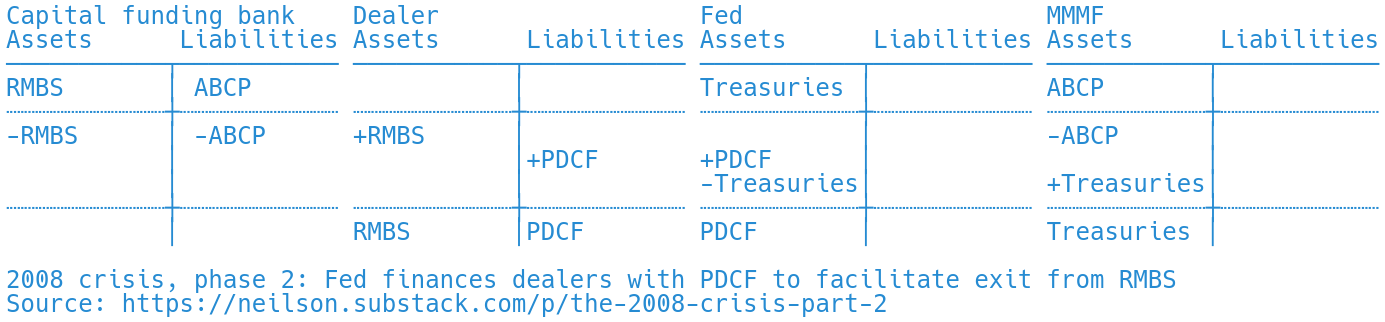

In this second phase of the crisis, the basic financing problem remained the same, namely finding a balance sheet to hold US residential mortgage-backed securities. But by this time, the MBS repo market had ceased to function. If dealers were to continue to be able to absorb the exit from RMBS, they would need another source of funding. The Fed tried to provide it with the primary dealer credit facility (PDCF). The PDCF marked an important shift for the Fed, in that it provided credit directly to dealers for the first time.

Importantly, the Fed funded its credit extension through the PDCF by reducing its stock of Treasuries. This was true of all of the Fed’s interventions during the second stage of the crisis. This meant that these interventions were accomplished through a change in composition, but not an expansion, of the Fed’s balance sheet. (This would change after Lehman’s failure in September 2008.) In the T accounts, I show the release of Treasury securities as providing an asset for money-market mutual funds to hold in lieu of maturing asset-backed commercial paper.

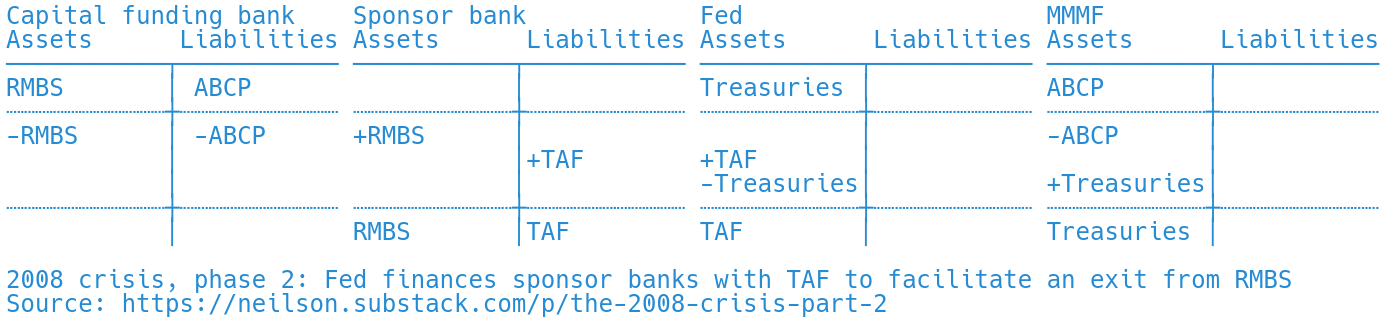

Banks were struggling to absorb RMBS holdings from SIVs they had sponsored. The Fed also extended funding directly to them through the term auction facility (TAF). The TAF, created before Bear but greatly expanded after, was structured as an auction with broad participation in an attempt to minimize the stigma to banks seeking recourse individually through the Fed’s discount window, though the financial mechanics were similar. (In retrospect, the concerns over stigma seem misplaced, but at the time it was a big part of the discussion.)

As the T accounts show, PDCF and TAF had a very similar balance-sheet structure. Where the PDCF supported the dealer system, the TAF supported the banking system. The two facilities were doing similar jobs, while intervening with different sets of institutions.

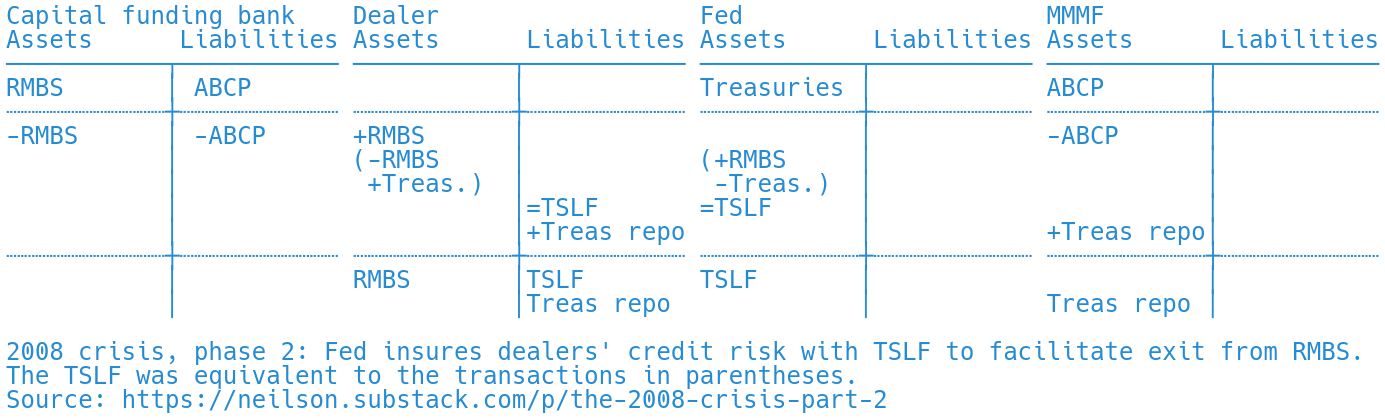

At this point in the crisis, MBS repo markets had broken down, but Treasury repo markets were still functioning. The Fed arranged the term securities lending facility (TSLF) to swap its holdings of Treasury securities for dealers’ holdings of mortgage-backed securities. Dealers could use the Treasuries as collateral to obtain repo financing.

The TSLF was more complex than TAF or PDCF. For the sake of clarity, these T accounts show, in parentheses, only the first leg of the swap, not the second leg which would undo the transaction 28 days later. The entire swap can be thought of as a loan of securities from the Fed to dealers, and is summarized as the TSLF entry, the Fed's claim on dealers. This provided collateral to allow dealers’ repo borrowing.

The turning point

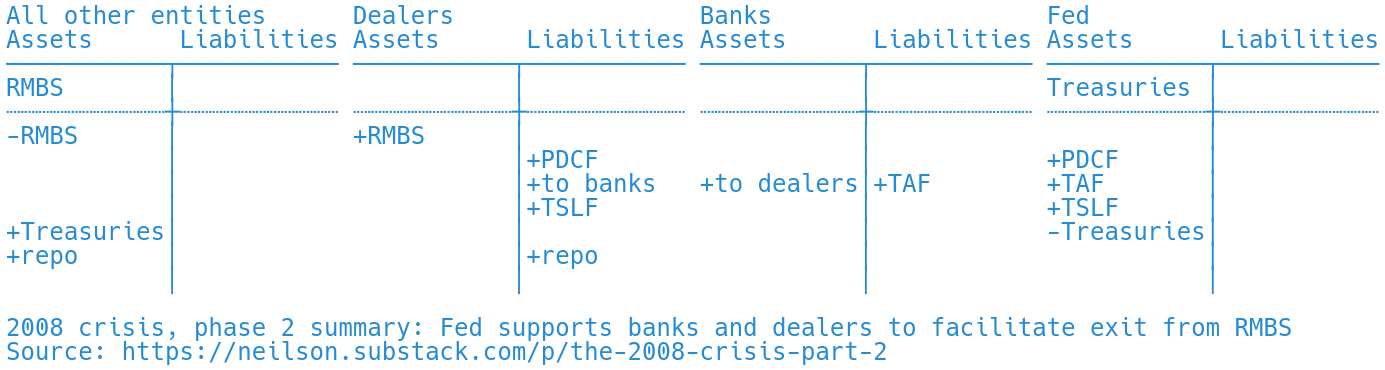

The second phase of the 2008 crisis involved considerable use, but not expansion, of the Fed’s balance sheet. The various liquidity facilities were all designed to fund the market’s exit from its RMBS position. This set of summary T accounts separates the Fed, dealers and banks. All other entities are consolidated, as a result of which the ABCP position is not shown.

This series of interventions prevented systemic failures after Bear’s collapse in March 2008. But the peak of the crisis was yet to come.

Please share

Soon Parted has been growing steadily since its launch earlier this year. If you enjoyed this post, please help others find it by sharing: