The 2008 crisis, part 3

After Lehman

This is the third part of a short financial history of the 2008 financial crisis. Part 1 is here. Part 2 is here. All of the crisis facilities are depicted as animated gifs here.

After Lehman's bankruptcy in September 2008, the Fed's interventions in money markets changed both in structure and in scale. Up to that point, lending through TAF, TSLF and PDCF had been achieved by changing the composition of the Fed's balance sheet without expanding its size. With the failure of two investment banks, and problems at other major institutions and throughout the financial system, the Fed after September 2008 embarked on a dramatic outright expansion. Existing liquidity facilities were expanded, funded by the creation of new reserves, and a number of new liquidity facilities were launched.

These steps would take the Fed's balance sheet from under $1 trillion before the crisis to more than $2 trillion by 2009. The pre-2008 financial architecture was gone.

Phase 3

Importantly, though the crisis had begun to affect the core of the financial system, the underlying refinancing problem had not changed. Capital funding banks ("shadow banks") held a position in US residential mortgage-backed securities, funded by issuance of asset-backed commercial paper. The ABCP could not be rolled over and no one wanted to take on the position in mortgages.

Under the September 2008 ABCP MMMF Liquidity Facility (AMLF), the Fed tried to address the liability side of this problem, by lending to dealers against their purchases of asset-backed commercial paper. The idea was to get dealers to hold the problematic debt; to ensure that they could do so, the Fed committed to accept that same debt as collateral:

Like the AMLF, the October 2008 commercial paper funding facility (CPFF) worked on the capital funding banks' liability side. With the AMLF, the Fed had funded dealers to hold the illiquid ABCP; with the CPFF, the Fed brought it onto its own balance sheet. This was funded, in the end, by issuance of new reserves.

Also ran

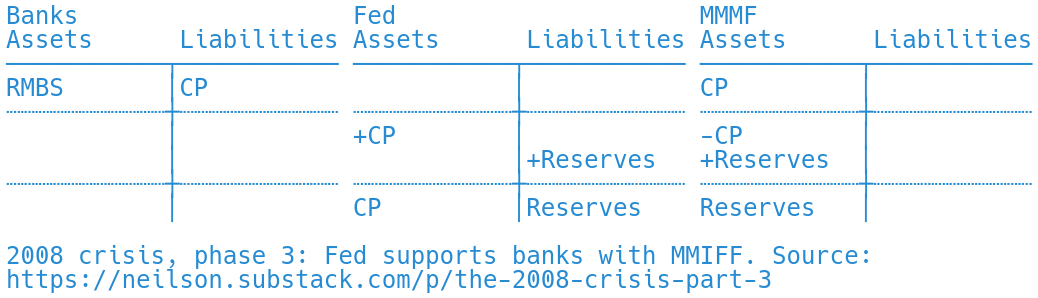

Two liquidity facilities should be mentioned for completeness. The first, MMIFF was never used; the second, TALF, was somewhat ancillary to the mortgage refinancing problem.

Mortgage-backed securities had been placed in off-balance-sheet shadow banks. But the commercial banks had offered explicit or implicit guarantees to these vehicles. As the off-balance-sheet structures failed, RMBS were dropping onto bank balance sheets themselves. Money market funds were wary of refinancing banks' commercial paper. With the November 2008 money market investor funding facility (MMIFF), the Fed sought to support both banks and money funds by buying the paper itself. The MMIFF was never used.

Finally, the November 2008 Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF). In the fog of the crisis, markets for asset-backed securities other than residential MBS had vanished. In an effort to support markets for student loans, auto loans, credit card debt, small business loans, and commercial mortgages, the TALF lent money to buyers of newly issued securitizations, accepting the ABS as collateral.

The beginning of the end

By the end of 2008, the acute phase of the crisis was over: the Fed had ensured the continuity of financial capitalism. Over the following months, the liquidity programs were wound down as the Fed launched a program to purchase mortgage-backed securities outright.

Looking back on these events from more than a decade later, there is a sense of inevitability that was hard to perceive at the time. In hindsight, the many liquidity programs were all trying to find ways to refinance a systemic position in mortgage-backed securities, and eventually that was achieved. At the time, though, the steps were taken without a clear systemic picture.

Dear Prof. Neilson,

I was recently made aware of your blog through the website of Prof. Mehrling while following his online course on Money & Banking. Thank you for your succinct and very informative writings. It really is a pleasure to read your posts. I wish you and your family a happy new year!

Oguz