The tokenization thesis

Citi's proposal for liability money on a distributed ledger

It seems clear that the writing is on the wall for public crypto: regulation is coming, and the heady days of the last two years are numbered. If there is a lasting impact, it will be through the incorporation of crypto technologies within the existing banking system. My recent investigations into the R&D being done by the banks have not yielded any unambiguous use cases. It is certain, however, that like me, they are spending a lot of time and energy trying to figure it out.

Citi's Tony McLaughlin seems willing to explore the question while remaining skeptical, appropriately so from the point of view of a systemic, incumbent financial institution. I have written previously about McLaughlin's observations on API-based banking. In two interesting pieces from recent months, McLaughlin opens up a number of important ideas that warrant more complete consideration. Here I want to pull out what he calls the "tokenization thesis," namely the arguments that tokens will win out over accounts as representations of value.

Not all tokens are bearer instruments

Payment by transfer of a physical coin or note can be thought of in two steps: first, the validity of the medium is checked (is the note counterfeit?), then ownership is transferred and the payment is final. Such is a bearer instrument, a token of value that is both proof of authenticity and repository of value. Bitcoin and Ethereum are digital bearer instruments: the blockchain algorithm confirms the validity of the payment and associates the value with the recipient's cryptographic keys.

The two functions can be separated. An unendorsed check, for example, is a proof of authenticity of payment, but it is a repository of value only for the named payee. Physical transfer of the check does not, by itself, transfer any economic value. Once endorsed, however, a check does become a bearer instrument.

Banking without liabilities

As bearer instruments, public crypto tokens Bitcoin and Ethereum have given rise to an asset-only financial structure. Value is represented only by ownership of the tokens. The tokens are not anyone's liability; they are based on a conception of value that arises from their scarcity-by-design, what I have previously called "crypto monetarism." Payment is completed by transfer of ownership:

In such a situation, the only way to be sure of being able to complete payments—that is, the only way to remain liquid—is to hold large stores of tokens, which leaves them vulnerable to loss and theft, as Poly Network learned the hard way.

Liability tokens

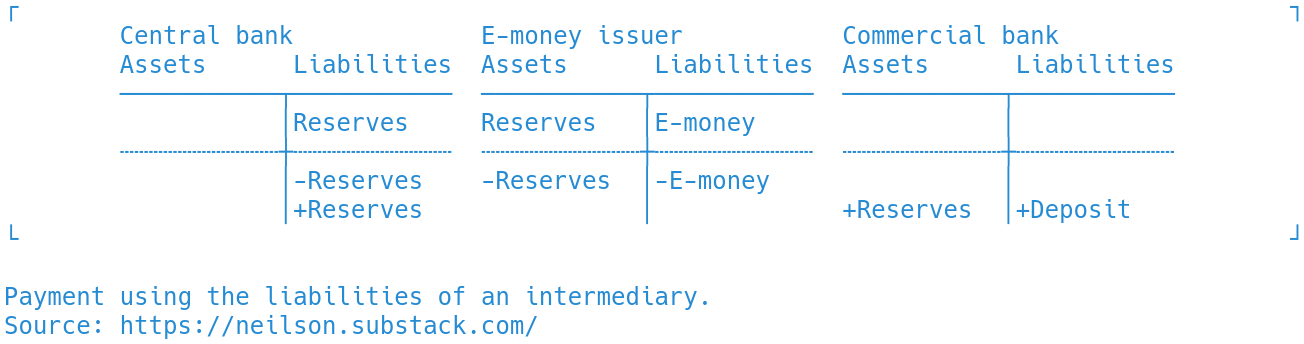

Two-sided instruments are preferred in commercial transactions over such an asset-only structure. If the assets of one actor are the liabilities of another, and the two sides can agree on terms, it is easy to expand and contract the supply of liquid assets quickly without holding large stores of tokens. This is how payment systems work. For example, if a user of e-money (e.g. a Visa prepaid card) wants to pay a commercial bank depositor, they can do so using liabilities of the central bank (the end-users' T accounts are not shown):

The receiving intermediary (the commercial bank, in this example) creates the deposit liability for its customer only once it has also received the corresponding asset (central bank reserves).

McLaughlin proposes a tokenized system, the Regulated Liability Network, to achieve this financial structure using tokens on a distributed ledger. Each transaction uses two tokens: a customer token, which requests the payment, and a settlement token, which confirms that the payment is funded. Such tokens are not bearer instruments. They behave more like checks than like banknotes, but each transaction requires two checks, one for the liability side and one for the asset side.

Why tokenize?

Token transfer, in such a system, would occur on a permissioned distributed ledger. Because the tokens are not bearer instruments, this would make no change to the legal structure of the financial relationships themselves: a deposit would still be a deposit, reserves would still be reserves. This is a big benefit from the point of view of existing institutions.

But as McLaughlin notes, it would mean big changes: instead of the account-based records that each individual bank currently holds, the distributed ledger (in its many copies) would hold that information for all participants. This would enable the benefits claimed for tokenization. The system could be always on, with no dependence on local business hours, because the existence of the two tokens ensures that the payment is funded with no further input from the sending bank. For the same reason, settlement would be instantaneous. And contracts would be programmable, because different participants could independently execute the same conditional logic, and be sure of reaching the same results, on their own copies of the distributed ledger.

Citi's concept has already attracted the attention of tech firms: R3, which has been busy building CBDC systems using its Corda blockchain, wrote an implementation proposal; and separately SETL, working with Amazon, built a simulation to show that the system could reach throughput of a million transactions per second.

Hard to say where this will end up. But for sure, we can count this among the more serious of crypto experiments.

Hmm. I suppose this raises the question of where (and why) it's useful to draw a distinction between "tokens" and "accounts." If all assets on the blockchain are associated with an owner address, that sounds an awful lot like everybody has blockchain accounts.

Is it the token-versus-account distinction that matters here? Or is the biggest change that Citi wouldn't have to manage the accounts using its own database? Or are they using blockchain as an excuse to automate things that, from a technological standpoint, could easily have been automated without blockchain?