Whatever it took

The ECB balance sheet, pre-crisis to post-pandemic

Debts record the pattern of surplus and deficit cash flows that arise from production and exchange. Yesterday's deficit agents, unable to settle payments at the time, instead promised to pay later. Those promises were the assets bought by yesterday's surplus agents. These promises survive as the assets and liabilities on today's balance sheets.

If in some systematic way deficit agents cannot find surplus agents to accept their debts, the payment system itself is strained. The central bank, by design, tradition and negotiation, absorbs the imbalances instead. The balance sheet of the central bank, then, is a record of those past imbalances big enough to reach the system’s center.

In its brief history, the European Central Bank has accommodated imbalances arising from the financial crisis, the euro crisis, and the pandemic. Each of these moments posed specific financial challenges for the euro area. The ECB is an inherently conservative institution, mostly following and not leading. So its balance sheet—technically the consolidated balance sheet of the Eurosystem—is a record of what had to be done to keep the monetary union intact.

Before the 2008 crisis, the ECB's balance sheet had a total size of EUR 1.2T. It was—in summary—a portfolio of bank refinancing operations, along with some gold and FX, funded by currency issuance. The monetary policy framework was made to work on a small quantity of reserves, similar to the pre-crisis US system though not as extreme.

(Figures are in EUR, e.g. 1.2T means 1.2 trillion euros. Note that here and throughout this post, I have gone through the ECB balance sheets as published and tried to reduce them to something more compact. I am certainly violating the legal definitions that constrain the ECB's own reporting. I think, though, that I am not misrepresenting the economic substance.)

The global financial crisis, especially during 2008, put a strain on interbank dollar lending. European banks could not finance their exposure to US mortgages. The ECB expanded bank refinance, shifting it to longer term (substituting LTROs for MROs). It also extended dollar financing to eurozone banks, with the exchange risk covered by the swap line with the US Federal Reserve. Here is the ECB's balance sheet at the end of 2008, after these operations:

The Euro crisis, over the next decade, tested the monetary union's political-economic coherence. The constraints of monetary union meant that when imbalances in government payments could not be financed in private markets, there were no exchange rates that could adjust, and so the ECB had to absorb them. The ECB purchased EUR 2 trillion in government debt and half a trillion of bank and corporate debt. This was financed by issuance of reserves, and closing out of medium-term bank refinance. By the end of 2019, just before the pandemic, the ECB balance sheet looked like this:

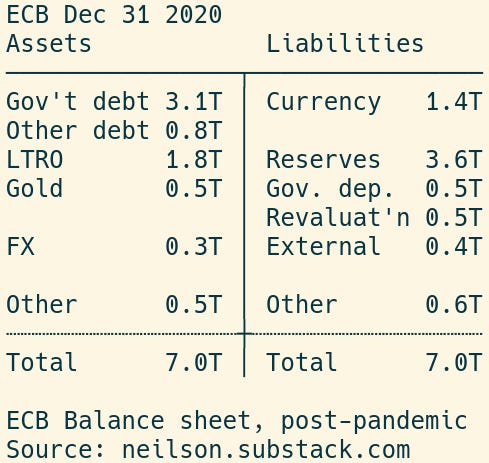

The COVID-19 pandemic has presented another cash-flow mismatch: the resources required for public health, on top of the usual resources required for life, versus the sharp restrictions on movement and business activity, which limited the usual sources of cash. The imbalance again fell on governments, and then once again on the ECB, which purchased further government debt and extended long-term support to banks, financed by issuance of reserve deposits:

The ECB's balance sheet as it is today carries the traces of the 2008 crisis, the Eurozone crisis, and the pandemic, in the form of a portfolio of claims on government, banks and business, financed by currency and deposits.

Three Crises for the Eurozone

In trying to get this decade-and-a-half of refinancing problems into a single picture, I came up with this:

This will be the basis for my thinking about the ECB going forward.