Archegos

Equity derivatives

Last week the fund Archegos imploded spectacularly, forcing its prime brokers, especially Nomura and Credit Suisse, to dump tens of billions of dollars' worth of shares in a dramatic fire sale. This comes close on the heels of the collapse of Greensill, with which Credit Suisse was also closely involved.

Apparently Archegos was exposed to prices of shares in ViacomCBS, Tencent and Baidu, among others, and declines in the prices of those shares led to a margin call—Archegos was asked to put up collateral with its brokers. Archegos defaulted, which triggered the fire sale as the banks tried to cover their positions. Late last week, the banks tried to coordinate the sales of shares to avoid driving down prices, but that had failed by Friday 26 March, when the story broke.

The scale of the fire sale, and the losses to the brokers (some $6bn at least), seems disproportionate to the movements in share prices. That suggests leverage. And Archegos seems to have entered its positions without much in the way of disclosures. If they had the exposure without owning the underlying stocks themselves, that suggests swaps.

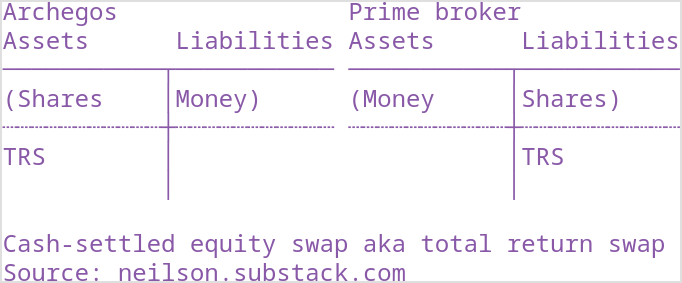

It is by now pretty clear that Archegos got its exposure to share prices using two types of equity derivative contracts with its prime brokers: total return swaps and contracts-for-difference. In both arrangements, Archegos contracted to receive the cash flows associated with share ownership without the disclosure and capital requirements.

How do these swaps work? A cash-settled equity swap, also known as a total return swap, entitles one party, Archegos in this case, to the income and capital gains associated with share ownership, without actually owning the security. The other party, the prime broker in this case, receives a fixed interest payment. The swap can be understood as matched parallel loans, a loan of money from the broker to Archegos and a loan of shares in the other direction. The investor pays a fixed interest rate to the broker, and the broker pays the variable total return on the equity (dividends plus capital gains) to the investor.

The two loans are combined into a single swap contract, the cash-settled equity swap or total return swap:

A contract for difference is a fixed-for-floating swap in equities. It can be understood as a cash-settled loan of shares. The prime broker lends shares short-term to the investor. The investor commits to return the shares at a fixed valuation. Until maturity, the investor can profit from an increase in the share price.

The loan of shares is combined into a single cash-settled swap contract, the CFD.

The two swaps are very similar. In both cases, the shares themselves do not change hands, minimizing reporting requirements and economizing on capital for Archegos. The prime brokers, too, can avoid putting up capital if they can offset the exposure elsewhere. I think of both types of swap as an asset to Archegos, because Archegos gets paid when the price rises, as if they owned the shares.

Unlike owning shares, however, Archegos has to pay cash when the price falls. This is what happened last week. Archegos exhausted its margin, likely because the fall in share prices, multiplied by the large notional exposure on the swap contracts, exceeded whatever collateral it had posted with its brokers. Archegos must have been out of liquid assets, and so the brokers needed to unwind their positions with Archegos. That meant they were left needing to sell the underlying shares. The banks tried to coordinate these sales, but failed, and it turned into a rush for the exit.

This looks like leverage, and its effects are similar. But leverage is normally understood as an asset position resting on borrowed money; here instead the leveraged position is achieved without any lending: the swaps are synthetic instruments that recreate the cash flows associated with lending without actually lending anything.

Archegos's motivations were transparent: they wanted to maximize exposure to equity prices, while minimizing disclosure and capital. But what was in it for the brokers? Nomura and Credit Suisse have been hardest hit by the fire sale, but Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, UBS, Mizuho and MUFG also had significant dealings with Archegos. Certainly they could charge fee income on the swaps. Perhaps also the prime brokers found that the swaps would allow them to maintain an inventory of shares, useful for transactions with other clients, while selling the risk to their customers. Or perhaps they thought they could offset the swaps with opposite swaps with other customers.

Whatever the plan was, it didn't work out.

In Sum

I still find it a little bit surprising that banks will repeat the same mistakes over and over. Archegos had highly geared positions, so they lost a lot of money on small price moves. Individually, the brokers had to sell collateral into a falling market. Collectively, they could have reached a deal and spread the losses out, but instead they blinked and didn't get a deal.

It will be interesting to see how much use prime brokers have been making of total return swaps and contracts for difference. Archegos's trades hit several large financial institutions—if there is more of this stuff buried, then maybe it will have a systemic dimension.

Please subscribe

I’m enjoying working on Soon Parted so far, and there seems to be no shortage of topics. I’m planning on looking at the ECB and BoJ balance sheets and monetary policy frameworks, tethers and stablecoins, and China’s e-yuan. Of course I’ll also follow any interesting financial breakdowns like Greensill and Archegos.

What will make this sustainable is an ongoing conversation with readers. So, if you appreciate this and other recent posts, please subscribe! Substack makes it pretty painless for both of us.

Ok, so I've read your posts on the nuts and bolts of the accounting reasoning and quadruple accounting elsewere, but the treatment of derivatives under this framework still confuses me a bit. Take the TRS (total return swap) example here for instance: I get the economic exposure treatment "swap can be understood as matched parallel loans", and I get why you combined the loans into a single swap contract on Archegos' asset side. What I don't understand is since balance sheets should balance, what liability entry on Archegos' liability side corresponds to the TRS recorded as an asset?

"Soon parted" is fascinating. A high-level didactic tool.

Each entry is the key to an understanding of an apparently complex world that, thanks to the explanations and its illustration through the stylized T-accounts, becomes understandable.

Gracias y felicidades. Iñigo