Plugging the leaks

Three refinancing channels, so far

Silvergate, Signature Bank, Silicon Valley Bank, First Republic, Credit Suisse: all banks fund a position in illiquid assets by issuing liquid liabilities. All banks therefore face the risk that their liabilities will be redeemed all at once. If a bank cannot pay its depositors, it fails quickly. If five banks fail in a row, one might wonder if there are not more failures to come.

To stop a panic from becoming systemic, depositors have to be convinced to stop asking for their money back. One financial mechanism that can do that is refinance—creating new financial channels to replace the channels that are failing. In this post, three refinancing mechanisms that seem to be active in the SVB panic.

Note this situation is evolving rapidly, and that I am writing without any privileged information, and so with a certain amount of speculation.

Private refinance

The First Republic deal is illustrative of a bank refinance channel. These T accounts illustrate. First Republic’s uninsured depositors ask for their money back (1). Depositors transfer these deposits into bigger banks (2). In a very public move last week, the big banks then made a $30 billion deposit into First Republic (3). In effect, the whole thing is something like this:

The end result (4) is a reintermediated chain of deposits. Depositors have succeeded in moving their exposure to the big banks; the big banks have made a statement by accepting exposure to the smaller bank.

Securities market refinance

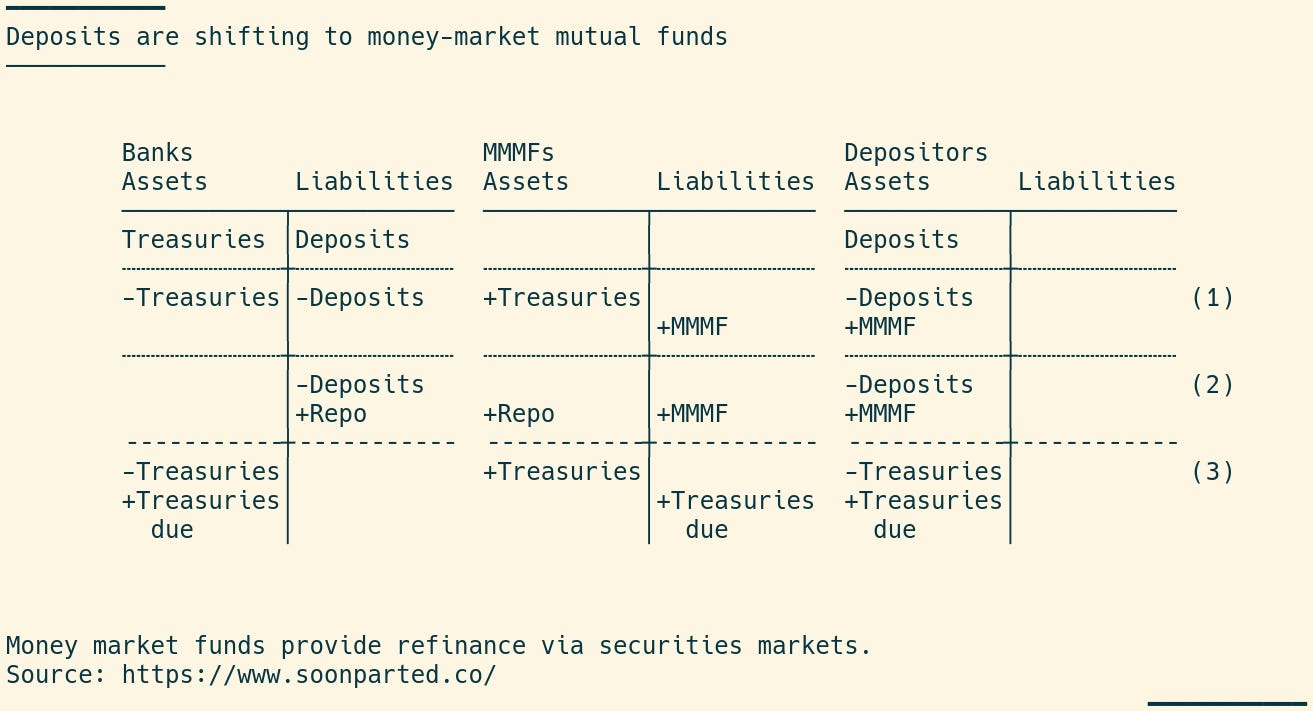

A second channel seems to run through money market mutual funds (money funds or MMMFs), which took in big inflows last week. These funds can invest only in a limited range of assets—roughly, government securities or repo against government securities. There are two main versions of this channel. Money funds are not as transparent as banks, so it may take some time to get all of the details.

From the FT story, MMMFs took in $120 billion last week, and from the Fed’s balance sheet (H.4.1), they did not deposit these funds at the ON RRP facility. The T accounts below illustrate two channels that are consistent with those facts. In row (1), depositors shift from holding bank deposits to holding MMMF shares. I suppose that banks sell securities to cover the outflow (bank securities holdings did decline last week, evidence in favor of this mechanism). Money funds buy those same securities with the newly deposited funds:

Another possibility is shown in row (2)—rather than selling securities, banks can replace deposit funding by borrowing cash in the repo market. Money funds can provide that funding by lending their newly deposited funds. Row (3) shows the collateral flows: note that the Treasury securities end up in the same place as in row (1)—but with repo, there is a promise to unwind the transaction later.

Public refinance channel

A third group of refinancing channels is also open, using the Fed’s balance sheet. These T accounts illustrate. The Fed’s discount window allows banks to borrow, using their securities holdings as collateral. The money flows are shown in (2); the collateral flows in (3):

At the discount window, securities are accepted at market value. But marking to market would create big losses for some banks, so the Fed has created the bank term finance program (BTFP). This mechanism, shown in (4) and (5), is the same as with the discount window, except that the collateral is accepted at face value rather than market value.

More to come?

The big picture is a general move from less money-like toward more money-like assets, from deposits at small or peripheral banks to deposits at big or systemic banks. Each of these channels is an effort to slow that movement, by offering depositors something they might be willing to accept.

And each of these channels has a limit.