Tornado Cash

DeFi is playing a losing hand

Earlier this month, the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control announced that it had sanctioned the crypto payment anonymization service Tornado Cash.

All sides are playing to form: the Treasury’s statement claims, not implausibly, that Tornado Cash has been used by organized crime and terrorists to launder money and that the service cannot comply with anti-money laundering obligations. Crypto defenders, meanwhile, have responded that the sanctions are not only unjust and illegal, but also technically unimplementable.

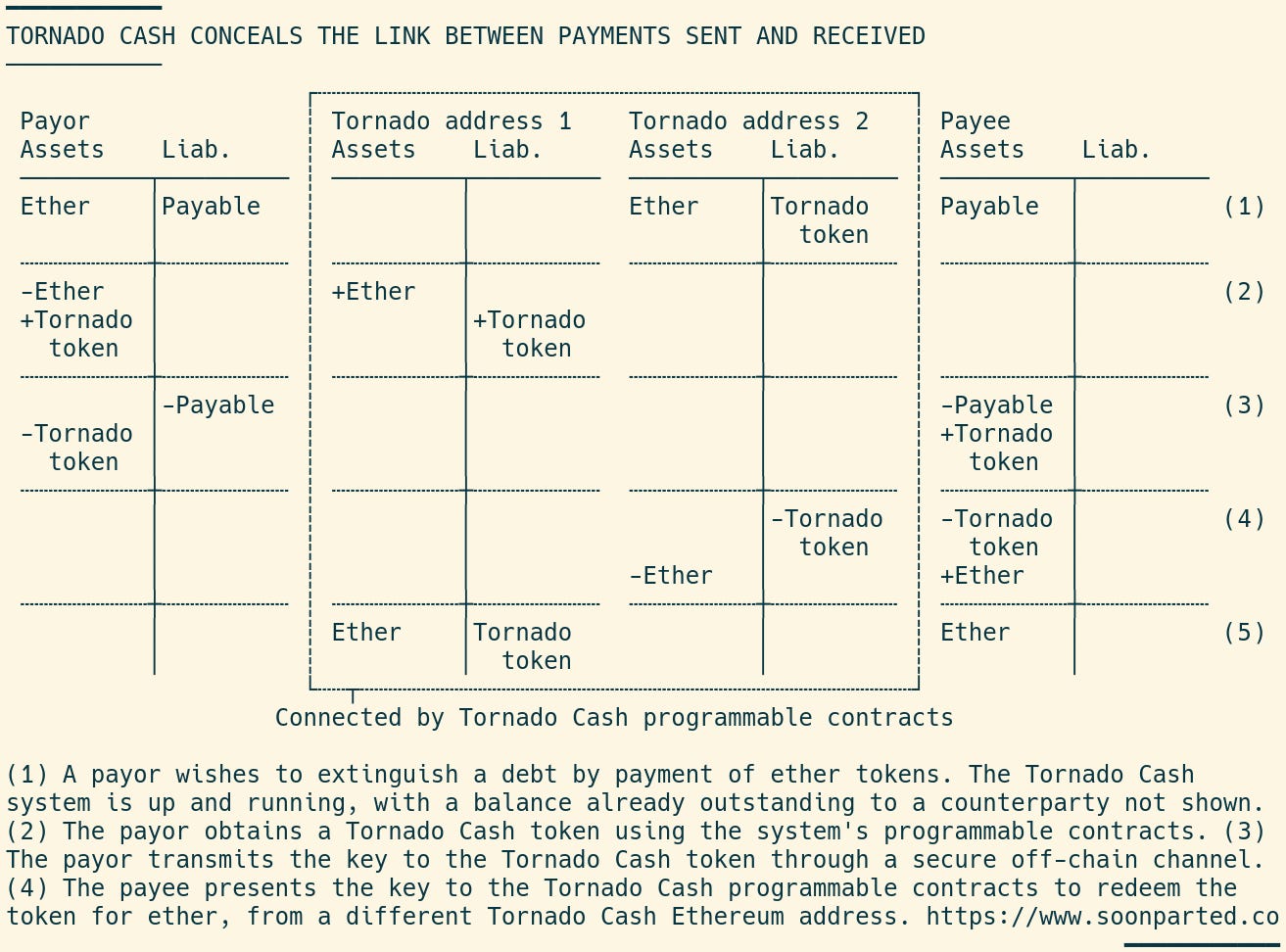

This is, in my view, a debate about the political economy of money. In this post: how Tornado Cash works (in words and T accounts), and some implications of the Treasury’s actions.

How does it work?

Tornado Cash is a computer program that facilitates anonymous payments. More precisely, it is a set of programmable contracts on the Ethereum decentralized ledger. Tornado uses the tools of modern cryptography, relying on large numbers and hash functions to make payments statistically anonymous.

The service allows users to pay each other by exchanging crypto tokens. All transactions on the distributed ledger are public, so making anonymous payments requires hiding the link between money in and money out. How?

A prospective payor buys a token from Tornado Cash, not unlike buying chips at a casino’s cashier. The tokens are available only in standard denominations, so that payments cannot be distinguished by value. The depositor can pass the token’s cryptographic key to another user, secretly and off-chain. That other user can withdraw the funds, so completing payment.

An observer could easily watch the distributed ledger to track these transactions, linking the funds coming in to the funds going out. But here Tornado Cash provides a large dose of cleverness—using its program, users can prove that they hold a valid token, one that has not yet been used, without revealing which token they have. The cashier will redeem their token because they can check that it is valid, but no one can trace where the payment came from.

Users still have to be careful not to reveal themselves in other ways. For example, anonymity is greater the more people are using the service—one wants a big crowd to hide in. Users also need to take care not to reveal their device’s IP address, and so on. If they do these things, Tornado Cash and similar services allow users to conduct quite anonymous transactions, even in the public space of the Ethereum ledger.

(Here is a nice intuitive explanation that goes into a bit more detail. Here is the Wikipedia page on zk-SNARKs, the mathematical basis for Tornado Cash.)

Why should we care?

The financial structure of a Tornado Cash transaction can be represented in T accounts:

The dashed rectangle shows that Tornado’s multiple addresses are joined by smart contracts rather than by a corporate or legal structure. The system accepts funds on one balance sheet, sending funds from another balance sheet. Financially, this is quite straightforward, but the system cleverly makes it impossible for observers to connect the money coming in with the money going out.

Banking businesses, those with assets and employees, cannot provide such services: they are required to comply with know-your-customer and anti-money-laundering directives from regulators. If they fail to do so, they face civil or criminal process in the legal system. But Tornado Cash works without any legal entity. It has no assets or employees, and no human intervention is needed for its process of payment intermediation.

Defenders of Tornado Cash, or crypto idealists more generally, note that the system is fully automatic, something like an ATM but without even physical assets that could be confiscated. The code cannot even be switched off, embedded as it is in the distributed ledger: copies already exist on every computer that contains a copy of the Ethereum blockchain. Usage of Tornado Cash has increased since the OFAC sanctions were imposed, driven in part by trolls sending small sums to notable figures to make them complicit.

What it means

Regular readers will not be surprised to learn that I think crypto is playing a losing hand. Do Tornado’s defenders expect that Treasury will roll over, simply giving up on enforcement? There are plenty of channels by which authorities can control the service: even if the Tornado Cash code itself cannot be stopped, most users access crypto through exchanges and wallets, which are businesses with employees and assets and which can be punished in the usual way for facilitating money laundering. It would not take too many prosecutions to convince most users to give up their anonymity.

More extreme scenarios can be imagined: holding miners or programmers criminally liable, for example, would put crypto infrastructure in enough legal ambiguity to make it unattractive to most users. Long run, governments have the upper hand here. Public distributed ledgers will, in the end, either be confined inside walled gardens, like casinos, or they will be absorbed into regulated institutions. The Tornado Cash case, and surely more like it still to come, will play a part in defining the specifics of this future arrangement.

Note: I am closing comments on Substack for the time being: tending them has become quite time-consuming. Comments are still welcome on Twitter and by email. Note also that you can reply to the newsletter itself to send me a note.