Wild SPACulation

This week Grab, the Singapore-based tech company and superapp, will go public by merging with a special purpose acquisition company launched by Silicon Valley's Altimeter. The $40 billion valuation makes it the largest SPAC deal ever. I would not be the first to suggest that the end is nigh.

But what is a SPAC? The past two years have seen a huge boom in the use of special purpose acquisition companies as a way to take private companies public. Also referred to as blank-cheque companies, a SPAC works by raising money for an empty shell, listed on a stock exchange, which then seeks out a private company to merge with. The end result is a listed public company, financed by the SPAC's public and private sale of shares, and holding the business activities of the private company.

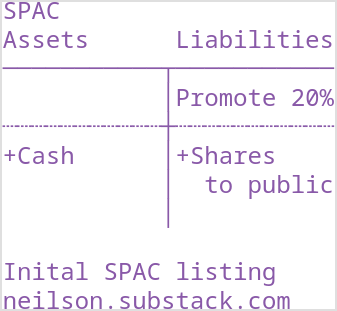

The financial mechanics are not too complicated. The SPAC is formed based on a so-called promote, typically 20% of the equity of the blank-cheque company, that is distributed to sponsors for a nominal fee. Then the SPAC shares list in an IPO on a public stock exchange. The financial structure is something like this:

At this stage, the cash raised by the SPAC is tied up, and purchasers of shares are not able to cash out until the SPAC transaction closes out. One might expect this illiquidity to deter investors, but until quite recently investors have shown great enthusiasm for getting into SPACs at this stage.

Cash in hand, the SPAC's next task is to identify a private company to target for acquisition. Tech start-ups like Singapore's Grab have been typical targets. The private owners of such businesses are looking to cash out, and the SPAC offers a path for them to do so. The transaction is structured as a merger, and looks like this:

The SPAC uses the cash it raised in its public listing to purchase the ownership stakes of the existing equity holders. Funds may be brought in from an institutional investor to complete the purchase. This so-called PIPE (private investment in public equity) financing happens before details of the merger are made public. These institutional investors get access to this information but can buy the SPAC shares at the initial listing price.

In the merger, the business operations of the private company become the business operations of the new company, which also inherits the liability structure of the SPAC. After the transaction, the original owners of the private company can walk away, and the holders of the promote and the SPAC's listed shares now own the new merged company.

This deal structure is very attractive for the sponsors, because the promote can explode in market value as a consequence of the deal. For a nominal fee, sponsors get 20% of the SPAC, which becomes a smaller percentage of the merged company. But if the SPAC share price pops, that dilution is very well compensated.

All of this is possible, and attractive to owners of speculative capital, because SPAC deals are structured to achieve the effect of an IPO with the lower regulatory standards of a merger. It is pure regulatory arbitrage.

The pace of SPAC deals is now slowing, with PIPE financing taking longer to close, increased scrutiny from regulators, and less plausible deal valuations.

Out with a ...

Bang Maybe the SPAC craze will carry on, intertwining with the generally exuberant conditions currently prevailing in equity markets, supporting an increasingly complex and fragile financing structure, until an innocuous-seeming trigger topples it, destroying trillions in wealth.

Whimper Or maybe this is already the high-water mark for SPACs. A prominent deal will fail, a couple of bankers will have to find new jobs, the money will quietly dry up and everyone will find something better to do.

Also

Ayoze Alfageme wrote a nice review of Minsky.