Let’s make macro more fun

Capital formation in T accounts

One of the highlights of last month’s YSI Money View Symposium was a conversation between Perry Mehrling and the BIS’s Claudio Borio, on the subject of macroeconomic accounting. From my point of view, this was a step in the compelling but rarely satisfying project of reimagining macroeconomics. A feasible near-term outcome of that project, I think, would be a collection of better ways of thinking about large-scale economic phenomena using a chalkboard or a napkin. I think this could support better conversations about political-economic infrastructure, systems and policy.

Both Borio and Mehrling have worked against one of the major limitations of the national accounts, namely that they make little room for money and finance. This amounts to taking a major flaw of macroeconomics (its limited view of money), reproducing that flaw in the accounting process (by constructing national accounts without finance), and then building an empirical approach using that flawed data. We would be justified in calling it circular unreasoning.

My own approach has been to build using compact examples, and among these examples, accounting for capital formation is always a stumbling block. Below, a way of accounting for capital accumulation that is simple enough to remember, accurate enough to win an argument, and which makes a specific place for financial relationships.

Adding T accounts to macro

The main insight of macroeconomics is its use of sectoral reasoning: all economic activity is thought of as occurring between a manageable number of groups (sectors), and then economic ideas are expressed as relationships between those groups. Most of what happens inside a sector is lost. If the sectoral structure is well chosen, then the small set of relationships that remain can give insight into questions about employment, financial stability, prices and so on.

There is not a unique correct way to divide all economic activity into sectors. A common approach in macroeconomics is to think about households, government and business. One might further divide business into financial and non-financial, or to separate domestic business from business abroad. Another approach is to imagine an aggregate supply chain, and to think about primary, secondary and tertiary industry, arrayed in different positions between extraction at one end and final consumption on the other. The choice between different sectoral structures depends on the problem at hand.

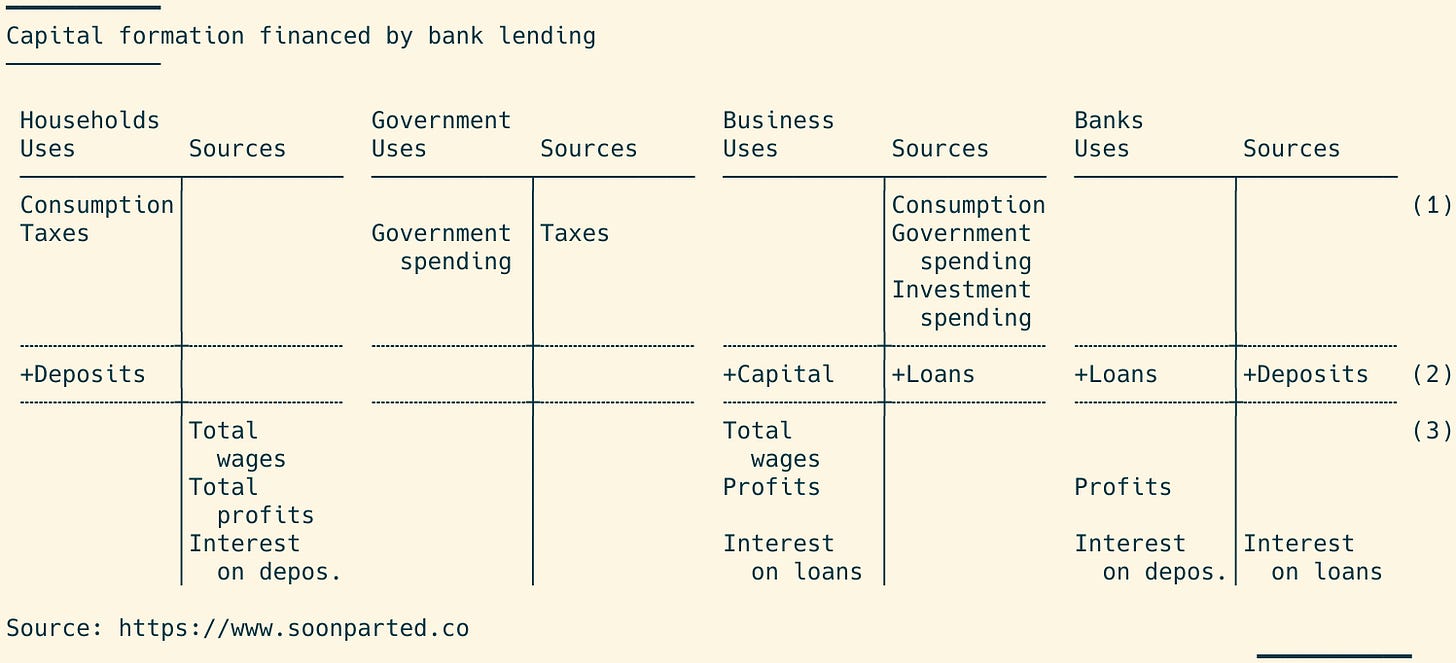

The accounts below, expressed using flow accounting (sources and uses), show one way to account for capital formation using four standard macro sectors. The picture is organized around a central “business” sector, which owns and operates the capital stock that allows domestic production, and with the concomitant power of allocating incomes. Such production is recorded here in three categories: consumption output sold to households, consumption output sold to government, and investment spending—capital goods sold to other businesses (1). Incomes are paid to households, as wages and profits (3). Government funds its consumption through taxes. In this example, the productive system is interpreted as closed, with no imports or exports, as though we are taking the global economy as a single system:

How it is written down is important: every entry in a sources and uses (cash flow) statement is a flow, a stream of value over a period of time, a year or a quarter or a day. Flows can be divided into those which do accumulate as stocks, and those which do not accumulate as stocks. The spending and income categories in rows (1) and (3) above are of the former category, corresponding to the income and expenses flows of business accounting. One could attach amounts of money to each entry, to verify that sources and uses balance properly. Here I have chosen concise presentation over exhaustive detail.

Note well, when I say that consumption flows do not accumulate, I am not talking about payments for consumption, which are the other kind, changes in money balances. I am talking about the consumption flow itself: goods being used up until they have no value. Consumption is a use of funds to households. It might be balanced by a decline in money balances, or by a flow of wages, both sources of funds.

Adding capital formation

So far, so much GDP, but here I also want to track capital formation (e.g.: building a factory, pharmaceutical R&D, or creating a tech platform) and the financial flows associated with it. One way to do this is represented in (2). Capital formation is a use of funds, like purchasing any asset. In this case, the asset is purchased by buying investment goods, which is the other side of the investment spending in (1), a source of funds for the businesses providing the investment goods, and which adds to the wages and profits these businesses can pay out.

For the buyers, new capital is paid for, generally, with borrowed funds, imagined here as a bank loan. The bank funds the loan by creating new deposits. Households can hold those deposits, and the accounting shows that they have available to them exactly the funds they need, by virtue of the increased wages and profits that the capital formation generated. This is of course the most famous accounting identity in all of macroeconomics, “investment equals savings.” But it is not a revelation, as it often appears in macro textbooks; it is a consequence of the choice of sectors and the insistence on complete accounting, neither more nor less. In this schematic representation, the only saving vehicle is money, but one could easily build a more complex financial system in the same framework.

Both loans and deposits might entail interest flows, and since the lending rate is higher than the deposit rate, banks can earn a profit. I have shown these three income flows in (3) above.

Let’s make macro more fun

This is a quick macro-accounting breakdown of capital formation. It leaves many gaps, among them the absence of prices, for capital goods, labor and financial instruments. For sure, incorporating prices would extend this picture and add to its complexity, but I think it would not change it fundamentally. The T account representation will only go so far before it becomes unwieldy, but its value is that it captures the conceptual structure correctly, and it can be put to use at a moment’s notice. The bigger jobs, of building a better accounting framework and so gaining better macro-financial data, will take much more than this.