Credit

Political economy of finance, note #1

This post is the first of a series of notes for a two-week intensive course on the political economy of finance that I taught at Al Akhawayn University in Ifrane, Morocco. Each note looks at a political-economic concept and an institutional structure. The notes are the skeleton of the course, fleshed out in the classroom with lectures, analytical techniques, discussions and supplementary texts.

Credit

Let’s begin with the notion of credit, from the Latin root cred- corresponding to the English word “believe.” Finance has a lot to do with borrowed money, and credit refers to the belief that the borrowed money will be repaid. Credit is a good starting point for understanding finance and capitalism, because although we can understand it quickly enough, its implications are complex and diverse. By studying this one important idea, we will find that we can understand a lot of other things too.

Economic activity is organized around the ownership of productive capital: the profits of a business are paid to the business’s owners, not to its employees or to anyone else. Becoming the owner of a business, or in other words organizing productive activity, is expensive, and so frequently one must borrow the money needed to do it. Such is the role of an entrepreneur, who takes ownership of productive assets using borrowed money. An entrepreneur can borrow only if lenders believe that the entrepreneur will one day be able to pay them back. In other words, the entrepreneur depends on those who are willing to extend credit.

Credit, we might notice, includes a sense of time: credit has a past, when the money was lent; a present, while the loan is outstanding; and a future, when the loan will be paid back (or maybe not).

Bank

Looking at capitalism through the lens of credit allows us to skip over many of the details of productive activity. Every industry, every technology, every production process has its own particular characteristics. Each has its own history, social structure and practices. These many details matter for some questions, but for reasons that we will see, focusing on credit relationships lets us quickly see the big picture. It is a way of starting from the center of the economic system.

We can go one step further. In the business world, some enterprises specialize in mining (say), others in the manufacturing of mobile phones, still others in the provision of accounting services, and so on. In much the same way, there are enterprises that specialize in extending credit to other enterprises. A business that specializes in credit we can call a bank.

To specialize in the provision of credit is, in some ways, not so different from specializing in mining or in accounting. Just as a mining company needs to employ people with expertise in extracting copper (for example) from the earth, a bank needs to employ people with expertise in evaluating borrowers’ ability to repay their debts. Just as a manufacturer of mobile phones employs people who can plan exactly how many lithium batteries (for example) will be needed on a certain day of a certain month, so that its production processes can advance smoothly, a bank needs to employ people who can plan just how much money will be paid back by borrowers on a certain day of a certain month, so that the bank can make sure it will be able to pay its own debts.

Balance sheet

The practices of finance are the day-to-day activities of the people who work at businesses that specialize in credit. These practices are also used by the people who do the work of government institutions that touch on finance—regulators, for example. Financial practices might also be used by people at other businesses who want to access financial services. Some of these practices are particularly useful for making sense of financial phenomena, and it is worth the time to learn how to use them.

One of the most useful techniques of finance is an accounting statement called a balance sheet. We will use balance sheets at a very high level, to record, summarize and communicate the property (ownership) and debt (borrowing) relationships that enterprises (businesses), governments and people enter into. Balance sheets usually show up in the context of accounting, and our use of balance sheets is generally consistent with what accountants do. Our balance sheets, however, are often simpler than the ones that accountants prepare. They are schematic, focusing on the structure of economic relationships:

This simple balance sheet is a prototype for all of the other balance sheets we will encounter, so let’s understand it carefully. The balance sheet is written in the form of a letter T, and so it is an example of a “T account,” which is a way of writing down accounting relationships. (We can use T accounts for other purposes as well, as we will see. We can also write down accounting relationships in other ways, without using T accounts, as we will also see.) Each T account corresponds to a single economic entity—one could prepare a balance sheet for a business such as Apple, for example.

A firm’s balance sheet is a statement of its assets and liabilities, which are shown on the two sides of the T account. Assets are always written to the left, and liabilities are always written to the right. On the asset side, we list the business’s property—what it owns. This could come in many different forms: a factory full of machines (for a manufacturer of mobile phones), property rights to a mine (for an extractor of copper), control of data and information (for a tech business). On the liability side, we list the business’s debts—the money it has borrowed. The options here are narrower: loans from a bank, bonds sold to investors, equity shares sold on the stock market.

The two sides of a balance sheet must always be equal in value—that is, assets must balance liabilities. In the example above, if the enterprise purchased property worth one million dollars, it must have taken on one million dollars in debt to do so. This simple statement—total assets equal total liabilities—is very helpful for understanding financial phenomena. It also contains some nuances and surprises, however, to which we will return later in the course.

Relationships of credit

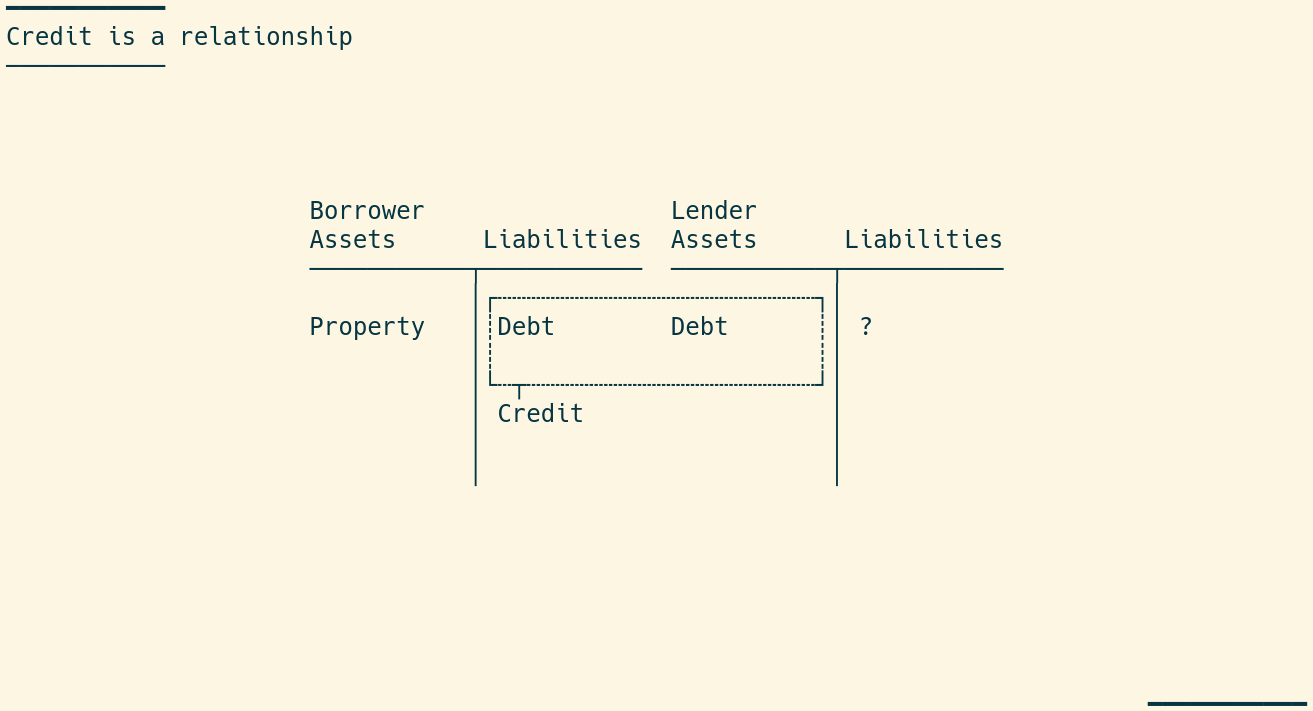

One of the nice things about T accounts is that two or more of them can be used together, to describe economic relationships between multiple economic entities. The two T accounts below show the prototypical credit relationship:

On the left, we show an entity that is acting as a borrower—a business that has borrowed money to purchase property. On the right, another entity, which is acting here as a lender—a business that has provided money to the borrower, with the hope and expectation of one day getting that money back, with interest. (The lender also must have liabilities, which will come to next time.) “Debt” appears on both balance sheets, as a liability to the borrower and as an asset to the lender. The debt is written twice, once on each balance sheet, but it is one thing, namely it is a two-sided credit relationship. Credit is a relationship that connects a borrower and a lender.

The purpose of this course is to help us understand the system of credit relationships, and by doing so, to better understand capitalism itself.

Political economy of finance

Credit (this post)