The end of the overnight reverse repo facility

For now

Most days, central banking is a matter of acting at the margins, leaning against the wind (as they say) with tight money when financial conditions seem exuberant, or fanning the flames with loose money when conditions seem gloomy. Monetary policymakers can’t simply select a desired level of economic activity, but they can shift the balance one way or the other. (Occasionally, central banking becomes a very different matter, catching a falling knife when markets break down—probably not today, though.)

To have a clear picture of monetary conditions, one must be able to say whether money is tight or loose. The question is less clear than one might have thought—here in late 2025, after a period of rising short-term rates, followed now by one rate cut, is liquidity scarce or not? After a long period of easy conditions, the zeroing out of one important balance sheet quantity makes a clear break on the path from loose to tight money.

The rise and fall of ON RRP

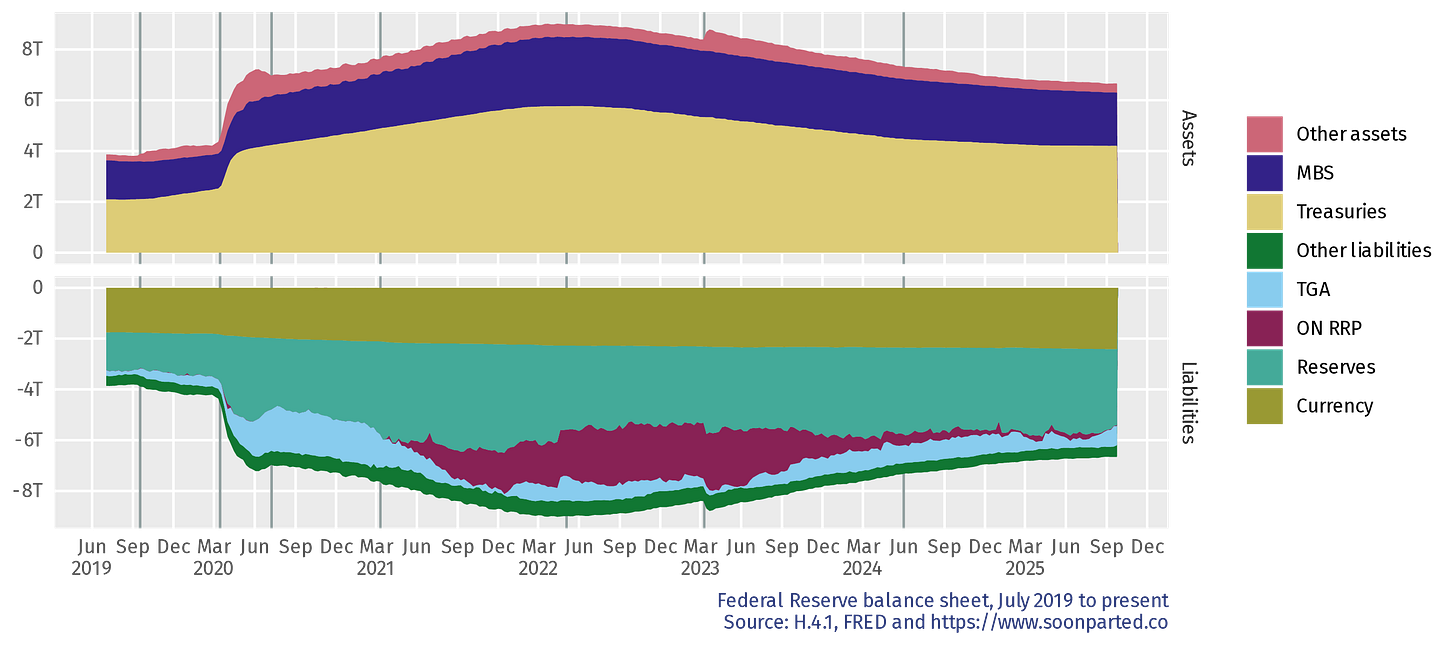

At the end of 2022, balances at the US balances at the US Federal Reserve’s overnight reverse repo (ON RRP) deposit facility stood just north of $2.5 trillion. As of yesterday (2 Oct 2025) the figure was $8 billion. Some day soon it may touch zero. The ON RRP facility is significant for its role in accommodating the Fed’s asset purchases at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. This picture of the US central bank’s balance sheet points us in the right direction:

The ON RRP deposit facility is a liability for the Fed, along with currency, the reserve deposits of US commercial banks and the US government’s deposits (the Treasury General Account or TGA). Following the outbreak of the pandemic in early 2020, the Fed followed its playbook from the 2008 crisis, launching a quantitative easing program that would eventually bring its balance sheet to more than $9 trillion. On the asset side, expansion took the form of purchases of Treasury securities and agency mortgage-backed securities.

To accommodate the asset purchases, the Fed had to allow expansion on the liability side as well. At various points both reserves and Treasury deposits grew, but by far the most interesting entry was ON RRP. The facility had been tested from 2014 to 2018, but those tests reached only about $100-200 billion. The Fed’s COVID-era asset purchases flooded the system with newly created money, and for a while ON RRP, meant to be a worst case, was the only option, particularly for money market mutual funds. It is not a stretch to say that the US central bank had to create an entirely new category of high-powered money to allow its balance sheet to double over the course of two years.

Starting in 2022, the Fed switched to contraction, and since 2023 that contraction has mostly been balanced on the liability side by reductions in the ON RRP facility. It has been contracting ever since, and is now almost closed out.

I guess that means everything’s back to normal

At the very least, it is a milestone, the end of an instrument that played a key part in the operation of the global dollar over the last five years. From an institutional point of view, it marks an end to the Fed’s five-year run of providing deposit services to money market funds. Back to the pre-pandemic normal, in that sense, where central money is held by the government and the commercial banks.

Or to put it another way—contraction so far has been absorbed by ON RRP; that pool is now exhausted. Any further contraction will necessarily be different.