The SNB taps its swap line

Dollar scarcity on the rise

The most dedicated of Fed-watchers will already be aware that the Swiss National Bank has in the last few weeks activated its dollar swap line at the US Federal Reserve. Below, a quick look at the mechanics of the central bank FX swap lines and a little bit of perspective.

What are the central bank swap lines?

The global financial system is strongly hierarchical, with the US Fed and the dollar in the dominant position. This dominance means that the Fed is able to serve as lender of last resort to other central banks—the Fed can provide dollars, quickly, by expanding its balance sheet on both sides. It has done so to considerable effect, for example in 2008 and 2020. The system of FX swap lines is the means by which the Fed provides dollars to the first tier of central banks (Bank of Canada, Bank of England, Bank of Japan, the European Central Bank, and Swiss National Bank).

The T accounts below describe a loan of dollars by the Fed to another central bank (here the SNB) using the FX swap lines. In step (1), the Fed creates new dollars in the form of a reserve deposit, which is the Fed’s liability and the other central bank’s asset. This is matched by a promise to return these dollars at maturity—typically 7 days. FX swaps also involve flows of collateral, shown in step (2). The top tier of global central banks have the privilege of using their own liabilities as collateral, so that the collateral flows are exactly the reverse of the dollar flows, except that they are denominated in a different currency, in this case Swiss francs:

Note that central banks in general don’t report the collateral flows on their published balance sheets.

The other central bank would then typically lend these dollars on to banks in its jurisdiction. This gave a way, for example, to provide dollars to non-US banks in 2008, when dollar funding markets froze.

In comparison

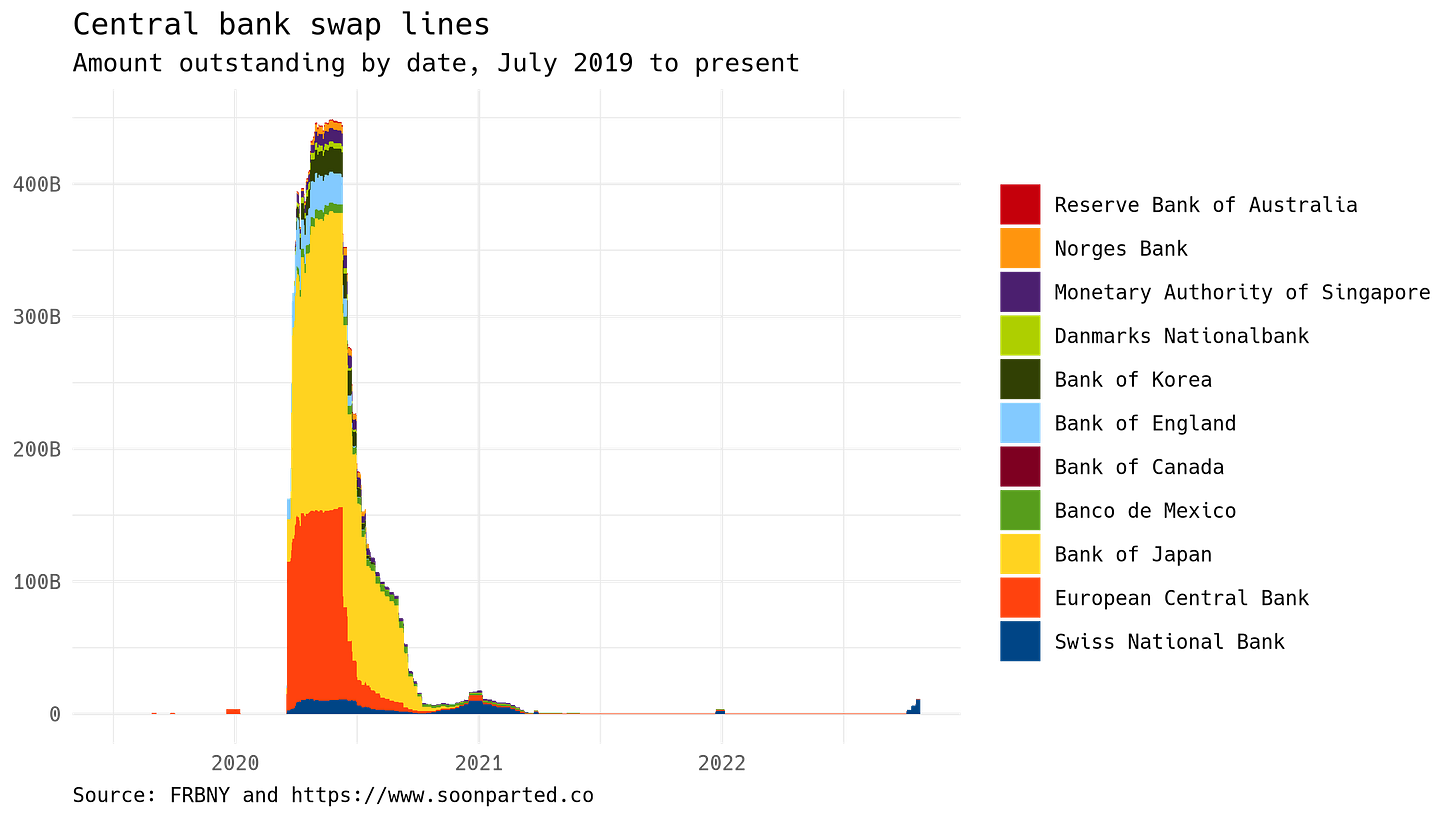

Because the Fed can quickly create dollars this way, and other central banks can likewise create their own currencies, the system of FX swaps can extend a lot of dollar funding very quickly. Indeed, the Swiss central bank has ramped its borrowing up to about $11 billion in the last month or so:

As the graph shows, the ECB has maintained a small ongoing dollar balance of about $200 million. Other countries tapped their swap lines in a limited way around the beginning of 2022. But the SNB activity is a big increase.

Before we get carried away, though, we should put this in some perspective. This version of the graph includes the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Note the change in scale on the vertical axis, and note how small that $11 billion looks in comparison:

In March 2020, the Fed lent $300 billion in ten days, with another $100 billion not far behind. The usual top-tier central banks all borrowed dollars, and temporary swap lines were extended also to other central banks. This borrowing contracted quickly, too—half paid off by July, most of the rest by September.

Still too soon to panic

This is precisely the point of the central bank swap lines: they can create a huge amount of the best international money, very quickly. That explains their use during liquidity crises. But by the same token, they are a temporary tool, drawn down essentially to zero in normal times.

So the SNB has activated its swap line. I don’t yet see evidence that this is part of a wider dollar liquidity crunch, although there have been many smallish bouts of instability lately. Maybe it will prove to be the beginning of something bigger. At the moment, however, the numbers are rather large for Switzerland, but still very small for the Fed.