Won

US monetary policy, the world’s problem

Yesterday the Fed raised US overnight policy interest rates by 75 basis points. Six months ago, the bottom of the target range for dollar overnight interest rates was zero; now it is 3 percent: monetary conditions have changed rapidly. The macro context now is one of increasing fragility: as tightening monetary policy reimposes financial discipline, underlying financial pressures will come to the surface more frequently. The interconnectedness and complexity of the global financial system mean that it is difficult to say exactly where and how problems will emerge—one minute it’s Terra/Luna; the next it’s EM sovereign debt.

In the last two weeks, there have been indications that South Korea could be pursuing a dollar swap line with the Fed. The country and its financial troubles are big enough that a crisis could have systemic repercussions. Moreover, the underlying issues are not specific to Korea, so an outline of the problem could serve as a blueprint for other financial breakdowns yet to materialize.

Interest rates and exchange rates are not two different things

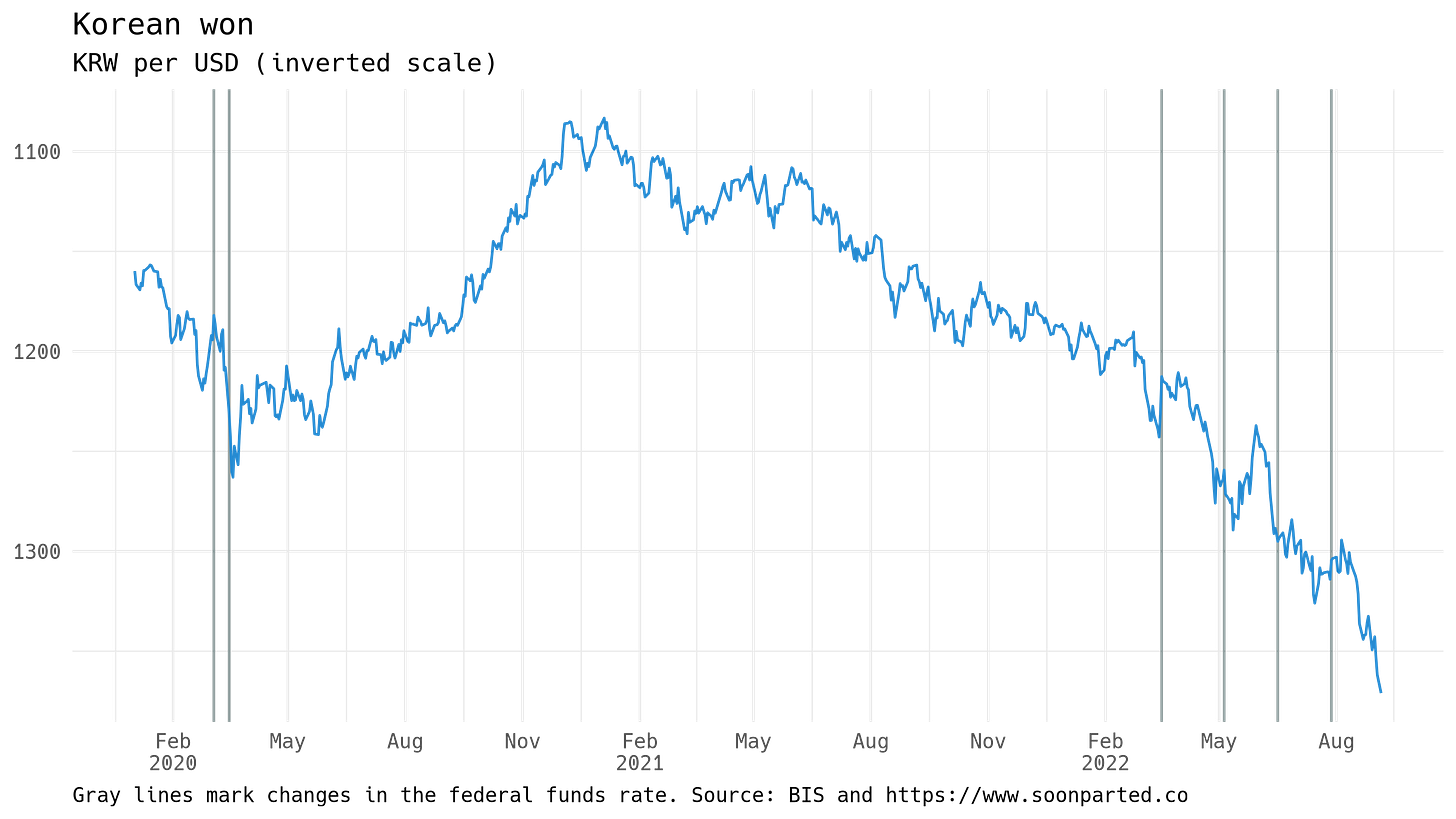

On the surface, the issue is the rapid depreciation of the Korean won relative to the US dollar, beginning in early 2021. This graph shows the price of one USD in KRW, using an inverted vertical scale to correctly convey the won’s declining value. The gray lines show days on which the Fed changed its targets for policy rates:

In words: holders of won are finding that dollars have gotten more expensive. This puts a strain on Korean firms with dollar-denominated debt, for example. Korean exporters, likewise, face rising dollar-denominated input costs. The fall has accelerated since the Fed’s tightening cycle began in March 2022, and now the country’s finance minister has started jawboning to try to stop it.

Why has the exchange rate moved so much? The dominant factor is the relationship between US and Korean monetary policy. When dollar interest rates rise, holders of won (or any other currency) can benefit by selling those positions, buying dollars with the proceeds, so earning the higher dollar interest rate. FX dealers end up with more won than they want, and so lower their asking price (the exchange rate) to try to get rid of it.

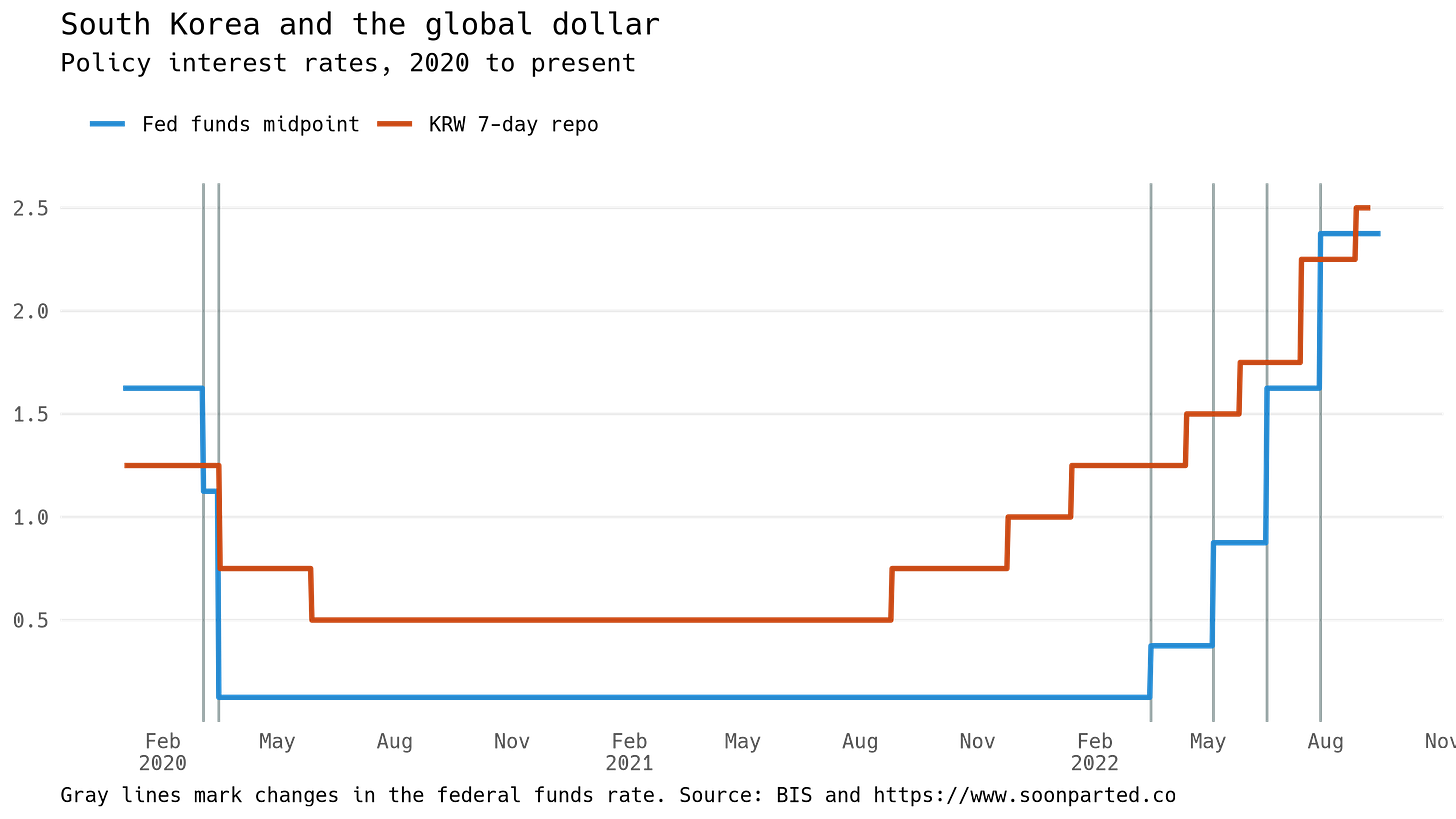

To stop this from happening, the Bank of Korea can raise its policy interest rates. This increases the compensation paid to holders of won, reducing the temptation to buy dollars and so supporting the exchange rate. And this is just what the Korean central bank has been doing. This graph shows the policy (i.e., managed) interest rates of the US and Korea.

Each time the Fed has tightened this year, the Bank of Korea has followed suit a couple of weeks later. The graph shows, however, that although the BoK has kept up with the Fed’s timing, the rises themselves have been smaller, so that the spread between the rates has narrowed. We can surmise that the Korean central bank knows that higher rates support the exchange rate, but that this comes at the cost of making domestic won-denominated credit more expensive—a tough trade-off.

Conclusion

A senior Korean official let slip last week that there had been talk of a dollar swap line between the Fed and the Bank of Korea. Official denials came quickly. Whether that happens or not, Korea’s case is a good illustration of how US monetary policy could lead to financial instability elsewhere.

The international effects of US monetary policy are almost totally absent from Fed communications, in the minutes of FOMC meetings for example. The Fed is a US institution whose formal accountability is to the US public, whatever opinion one might have about that fact.

Whether it is discussed or not, global financial instability is one of the possible side-effects of raising interest rates, and could be enough to force the Fed to pause or reverse its rate hikes.