Cash–futures basis

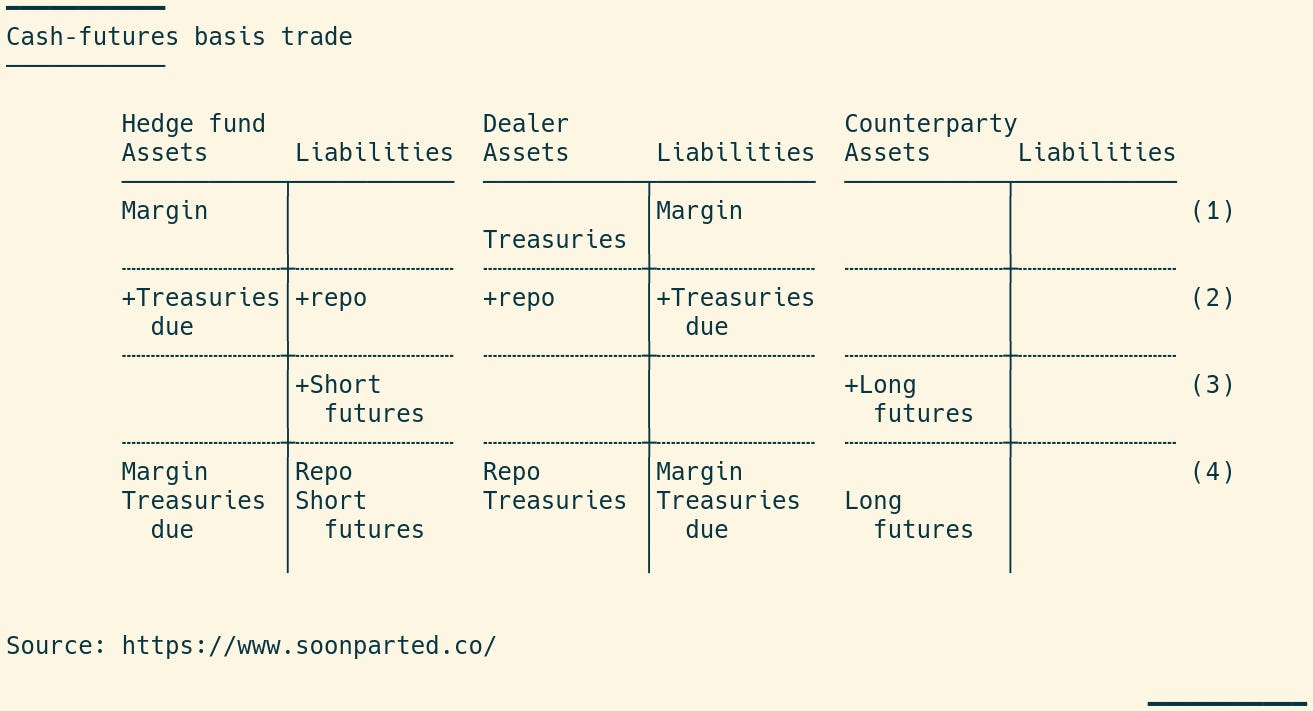

The missing T accounts

The BIS, the Fed and the FT have all recently pointed to the cash–futures basis trade in Treasuries as a potential source of financial instability. The price of a Treasury futures contract converges to the price of the underlying bond at maturity, so if the current futures price is above the current spot price of the security, the trade offers an apparently riskless profit. The basis trade uses borrowed funds to buy a Treasury security, while simultaneously taking a short position in the same security using the futures market.

To add something of concrete value to what has already been said by others, I have tried to clearly describe the balance-sheet relationships involved. My version of the story begins (1) with Treasury securities in the hands of a securities dealer. A hedge fund, observing the gap between futures and spot prices, borrows funds from the dealer in the repo market and uses them to buy a Treasury security. Immediately they post the same security as collateral with the dealer. The speculator will not be able to borrow the full value of the bond, so a margin deposit will be needed to cover the haircut (2).

The other side of the arbitrage is to enter a short position in a Treasury futures contract (3). This is done on a futures exchange, and will also require the speculator to post some margin at the futures exchange (not shown, to keep it to three T accounts). At this point, the balance sheets are as in row (4) above. For the hedge fund, the only cash required was the margin.

The T accounts don’t show prices, but the speculator enters the position when futures prices are above spot prices. When the gap eventually closes, as the futures settlement procedure ensures that it will, the short will become cheaper to deliver relative to the value of the bond. That is true even if prices drift up or down while the position is open.

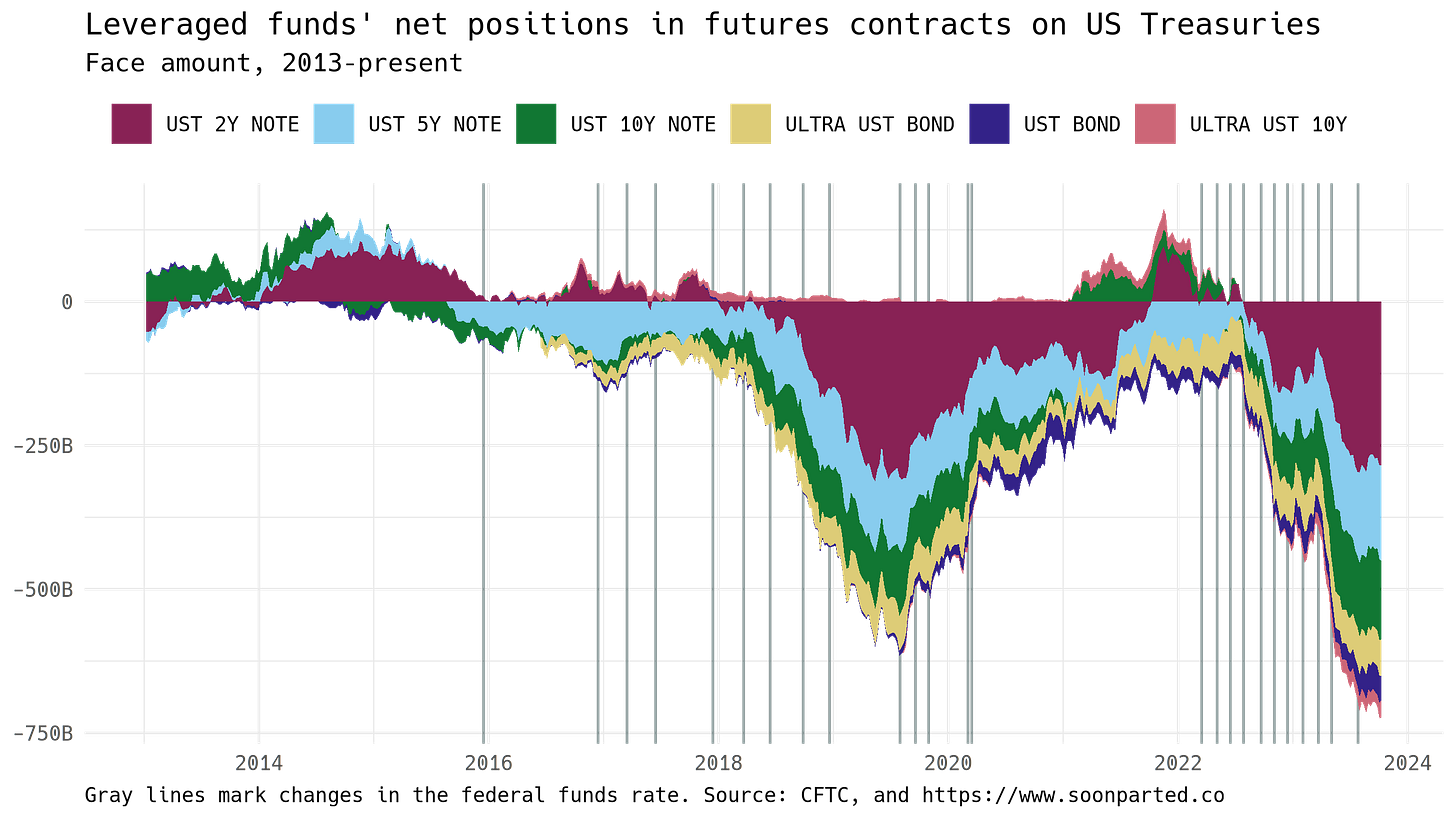

It seems that there has been a lot of interest in this trade. This graph shows net positions (long minus short) of “leveraged money” investors, based on data from the CFTC. The various colors in the graph distinguish the different Treasury futures contracts available. Vertical lines show dates on which the Fed changed the target for the fed funds rate. Hedge funds’ net short positions have grown from about $100 billion at the beginning of the tightening cycle, in early 2022, to close to $750 billion now:

This trade has a cost, and it has some liquidity requirements. The daily cost of staying in the trade is the interest on the repo borrowing, a bit over 5%. There are three liquidity requirements that I can see. First, the repo borrowing has to be rolled over every day. Second, variation margin payments must be made on the futures if prices rise. Third, the bond or cash equivalent must be delivered at futures maturity. The third is well covered by the long position in the underlying security. It is the other two that could leave hedge funds high and dry.

Bond prices have been mostly falling, so as long as futures prices also fall, the short futures position is generating cash every day. But if that were to change, if bond futures prices start to rise, then the shorts will have to pay cash every day instead. Rolling over the repo also carries some liquidity risk. As bond prices fall, the same bond gets you less cash each day in the repo market. Anyone in the basis trade will have to raise other cash, or close out their trades. Given the scale at which this is being done, either of these could quickly become a big deal.

The trade is guaranteed to be profitable at maturity. But it is not riskless: the relevant risk is liquidity risk. Speculators are not guaranteed to remain liquid until maturity.