China’s difficult choices

The missing T accounts

Michael Pettis, a widely respected observer of the Chinese macroeconomy, writes in the Financial Times and in Foreign Affairs this week of “China’s difficult choices.” The argument, simply put, is that a US recession will surely reduce China’s exports, threatening the livelihoods of the people whose incomes are paid by Chinese exporters. There are only a limited number of paths by which government policy could try to offset the lost income, says Pettis, and the only good way—income redistribution towards lower-income households—seems politically infeasible.

Pettis thinks in accounting terms, which I find helpful. But he reasons in terms of GDP and national accounts, which makes it hard to see the monetary parts of the puzzle that I think are important. So in today’s post, I provide a flow-of-funds accounting framework within which we can understand Pettis’s argument, much of which I agree with. I also add my two cents.

A pocket flow-of-funds framework for China

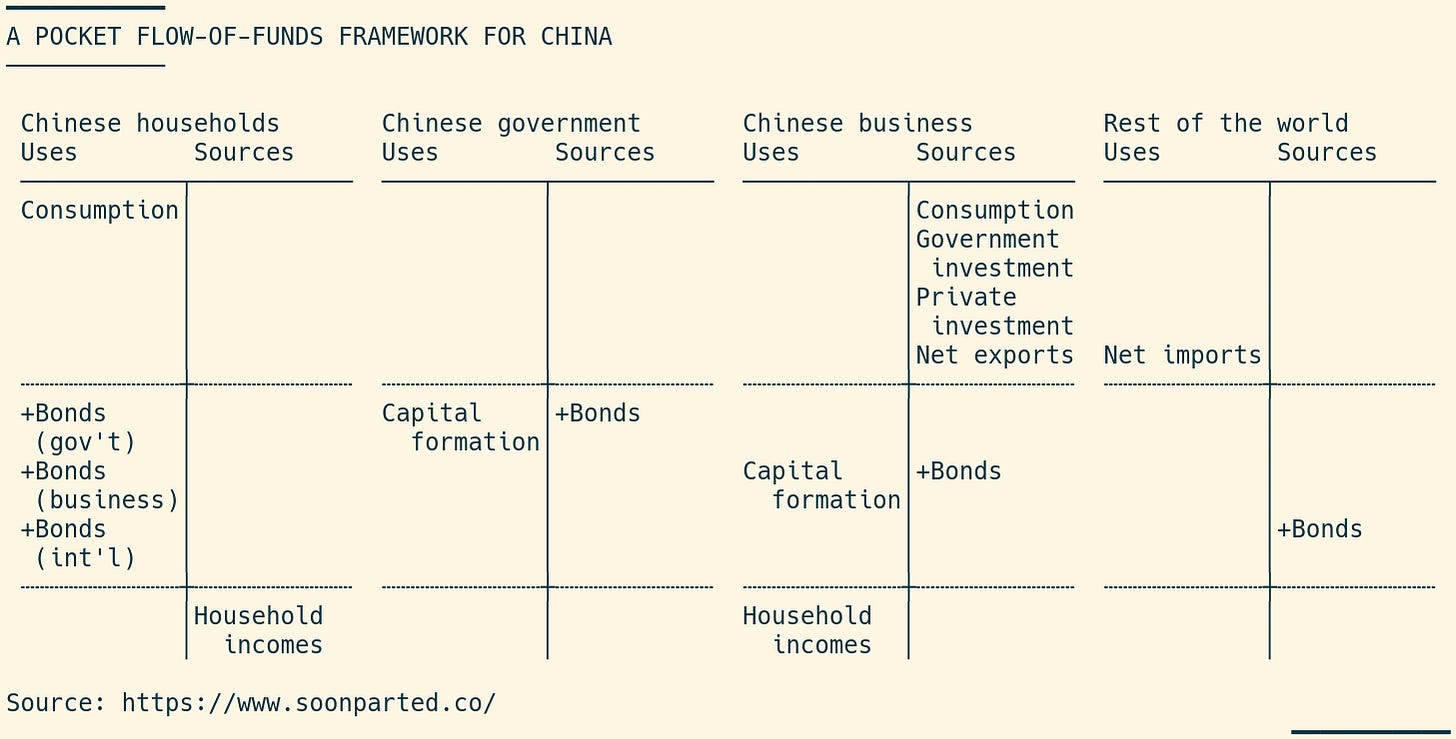

The T accounts below show a schematic flow-of-funds framework. I have tailored it for this discussion about China’s economic system, but with modest adjustment it applies anywhere. Because we are talking about spending and financial flows, I use flow accounting (i.e. sources and uses): every entry represents a flow over time (three months, say). The accounting is complete: if we put numbers to every entry, then total sources would equal total uses for each sector, and each source would correspond to a use. I use no numbers here though—this is a schematic argument.

We can think of the Chinese economy using four macroeconomic sectors. To the left are households, who earn income, spend on consumption and save the rest by buying bonds. The government sector borrows and uses the funds to build public capital (say infrastructure). The third sector, business, is where most of the action takes place, on which more below. These three Chinese sectors are balanced by a single sector for the rest of the world, showing only the international payments into and out of China. Here is the whole picture:

The tricky part is the treatment of capital. Capital formation is a use of funds to government and to businesses, who borrow to pay for it. This corresponds to a source of funds for the businesses that supply those same capital goods, who in turn use the proceeds to pay incomes to their workers and owners. This spending is called “investment” in the NIPA framework. In total, the capital formation of government and business is balanced by investment, and bonds are issued and purchased to pay for it.

Lots of things are absent from this picture. Households hold bonds not just directly but through a financial system that is not shown. Governments do a lot of things other than investment, including taxation. Imports and exports are both much larger than net exports, but I have shown only the trade balance. There should be foreign direct investment. There are other kinds of international capital flows. I have shown all borrowing as bonds, but there are also loans and money. All true, but: 1) this picture is pared down to the minimum needed for Pettis’s argument, and 2) one can easily add entries to talk about other flows (and I wish more people would do so!).

With this accounting framework in mind, Pettis’s point is easily stated. Net exports have been high and growing. Exports are sales, so a source of funds, for Chinese businesses. If those exports were to fall, as they might in the event of a US recession, exporters would have less to spend. To keep household income from falling, some other spending would have to rise to make up the difference—household consumption, private or government capital formation.

Whichever other sector spends more will, in turn, have to fund the increase. One can trace the options through the T accounts. If household consumption were to rise, for example, then necessarily either household incomes would have to rise, or savings (i.e., bond purchases) would have to fall. Pettis’s argument, to its credit, is mostly based on the coherence of this accounting picture.

One clarification

Pettis says “Like any country that saves more than it invests, China runs trade surpluses to absorb its excess production.” This is not wrong, though when speaking the language of macroeconomics I would advise taking more care with the terminology, because macro students are taught to insist that investment equals savings.

Luckily, the T accounts make the meaning clear: saving by Chinese households is greater than investment. In the T accounts, household saving is just household incomes less consumption, and that saving buys the liabilities of other sectors (as it must). Both businesses and government (including local governments, importantly) issue bonds to finance capital formation. But those sectors’ combined investment spending is not enough to absorb all of household saving.

The leftover household saving is absorbed instead by the purchase of international bonds. This is necessarily true, simply because of the accounting: China is running a trade surplus against the rest of the world; so the rest of the world is running a trade deficit against China; so the rest of the world must be borrowing from China. Total sources equal total uses; each source has a use and vice versa. The point is that some of China’s domestic saving is offset by negative saving abroad. Investment does equal total saving, rest assured! But you need a flow-of-funds perspective to see it.

Who exactly within China is buying these bonds from abroad, I am not completely certain. It seems not to be the central bank, these days. Probably the commercial banks are doing some of it. But someone must be—that is what it means to run a trade surplus!

My two cents

I’ve gone on long enough with this macro lecture. To put it back into context, I suggest you listen to the two biggest first-names-only of market plumbing, Perry and Zoltan in conversation on Odd Lots last month. Around the one-hour mark, they talk about the possibility of China building up big stockpiles of commodities. In Pettis’s argument, that kind of inventory accumulation would count as investment. But it would be different from the investment he considers, namely spending on manufacturing capacity. And it would be different from increasing investment in residential construction, which is clearly already overdone.

Previously on Soon Parted

Once again, I set out to write about China and couldn’t keep it under 1000 words.

The list of candidates for the next crisis seems to keep growing.

By the way, this situation has not improved.