The PBOC balance sheet, part 3

Foreign assets in China’s banking system

For those who keep up with what the world’s central bankers are doing—as readers of Soon Parted tend to do—our attention has mostly been on anti-fragmentation in the eurozone, on balance sheet contraction in the US, and on rate hikes everywhere. While we wait for the future of the international monetary system, there is no shortage of past to sort through. In this post, I catch up with the foreign exchange reserve position of the People’s Bank of China, and of the country’s commercial banks. This is a continuation of two earlier posts, available here and here.

Three regimes of Chinese monetary policy

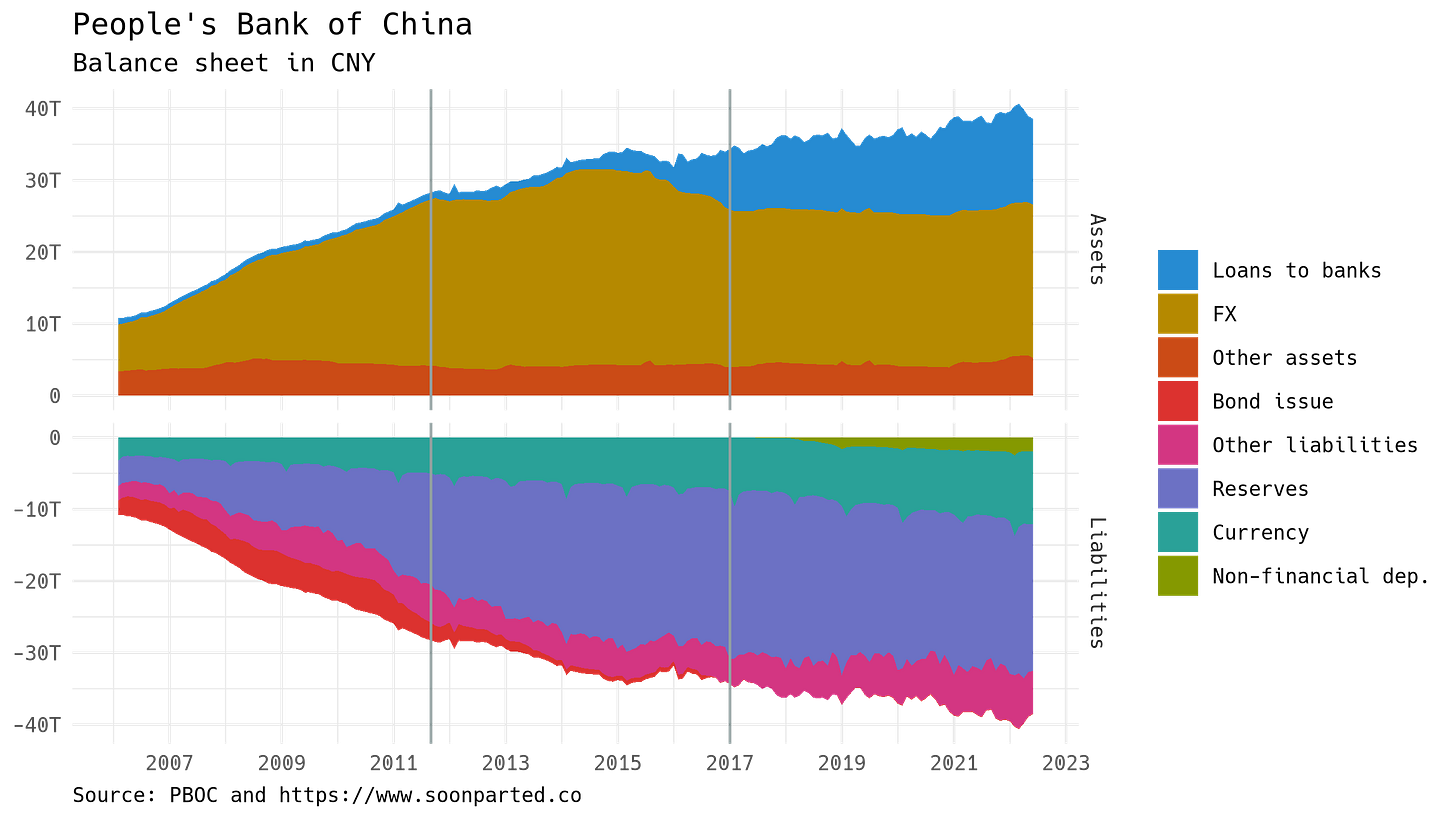

This graph shows the balance sheet of the PBOC, with assets above and liabilities below. Three main regimes of monetary management are clearly visible, and I have added vertical lines to separate them. From 2006 (when the PBOC’s public data begins) to 2011, China’s central bank was rapidly accumulating foreign assets. In late 2011, reserve accumulation paused and a transitional period followed. Starting in 2017, the central bank has held foreign reserves steady, instead expanding its lending to Chinese commercial banks:

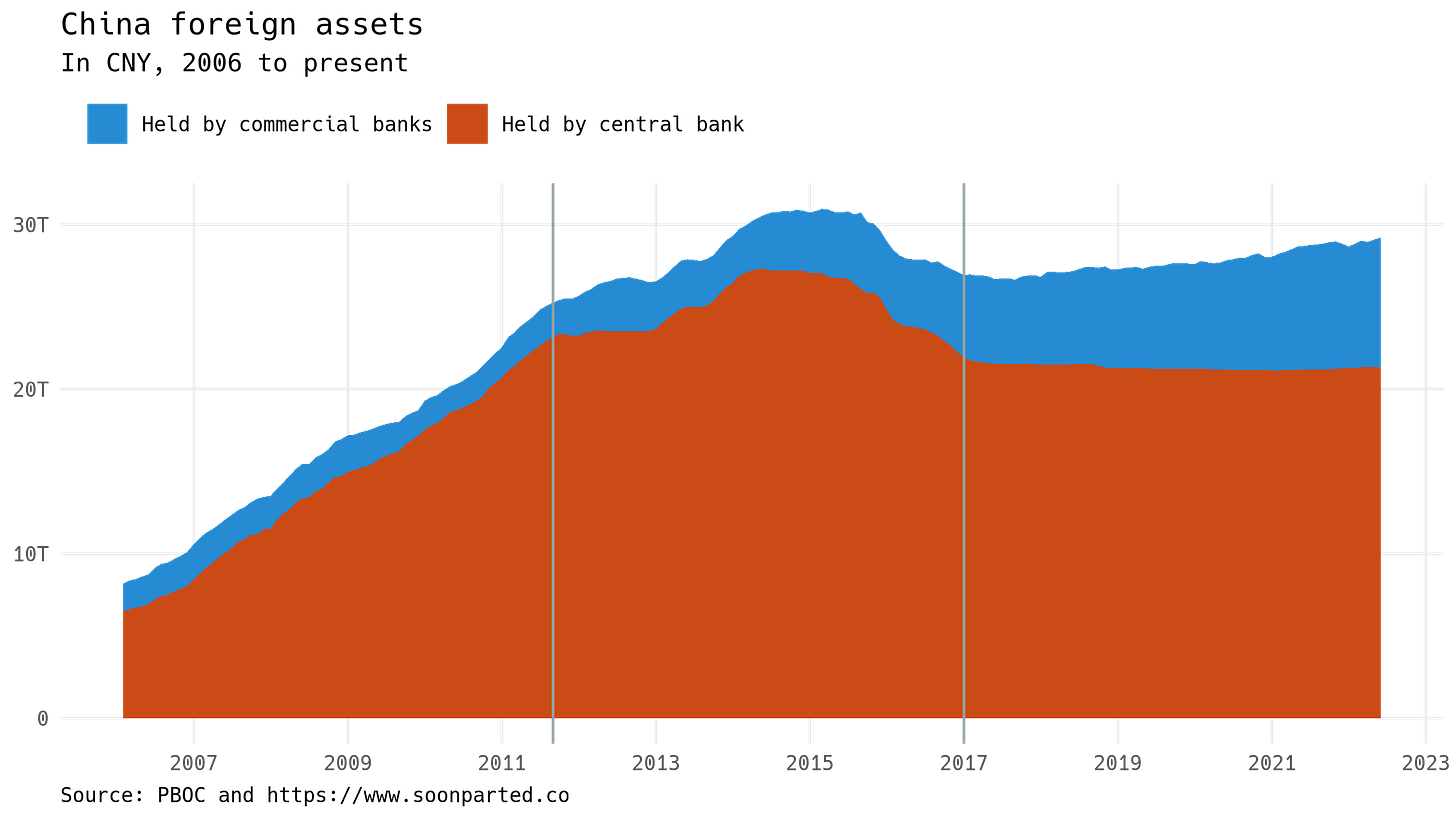

China has generally run a surplus of payments on current account, both before and after 2017. Mechanically, a current account surplus means that someone in the country must be accumulating foreign assets. We know that the PBOC did so until 2011, and less consistently until 2015. Who accumulated foreign assets after 2017?

Capital flows are carefully managed in China, so the simplest explanation—I argue—is that when the central bank stopped accumulating foreign reserves, the task was assigned to other actors. The PBOC puts out balance sheet data for commercial banks, which also happen to be the likeliest candidate. This graph combines the foreign asset positions of the central bank (in orange) and of the commercial banks (in blue). The vertical lines show the same periods as in the graph above (pre-2011, 2011–2017, post-2017):

The three FX regimes are easy enough to see: prior to 2011, the central bank accumulated foreign assets while the commercial banks held a small and roughly constant position. In the transitional period, commercial banks’ FX holdings began to grow, while the central bank’s rose and then fell in a series of adjustments. Since 2017, commercial banks’ holdings of FX has grown steadily while the central bank’s have been flat.

Not indicative of the dollar’s decline

This falls short of a full reconciliation of current account surpluses to foreign asset accumulation, and I don’t think such an exercise would be very informative anyway. This data convinces me that, since 2017, Chinese commercial banks’ balance sheets have been the resting place for an important piece of the country’s foreign asset accumulation. This shift is frequently discussed in terms of a widening of the exchange-rate target band, but it may be more informative to think about it in balance-sheet terms.

In fact, the Chinese banking system underwent several changes around that time: banks began accumulating a large position in Chinese government debt, they expanded issuance of their own bonds, and the central bank began lending to the commercial banks through regular and actively managed transactions. As I put the pieces together, I’ll write about it here.