The Fed would like to avoid a repeat of September 2019

Apart from keeping their fingers crossed that inflation will continue to cool, FOMC policymakers’ main concern these days is to avoid repeating the September 2019 repo crisis. Then, as now, rates had been recently been raised from the zero lower bound into positive territory; then, as now, the Fed was contracting its balance sheet; then, as now, hedge funds’ short positions in Treasury futures were at record levels.

Five years on, the 2019 repo crunch is eclipsed by the pandemic, both in memory and in lingering macroeconomic effects. But unlike the pandemic, the crunch was brought on—at least in part—by contractionary policy. Policymakers are keen to show they have learned from the experience.

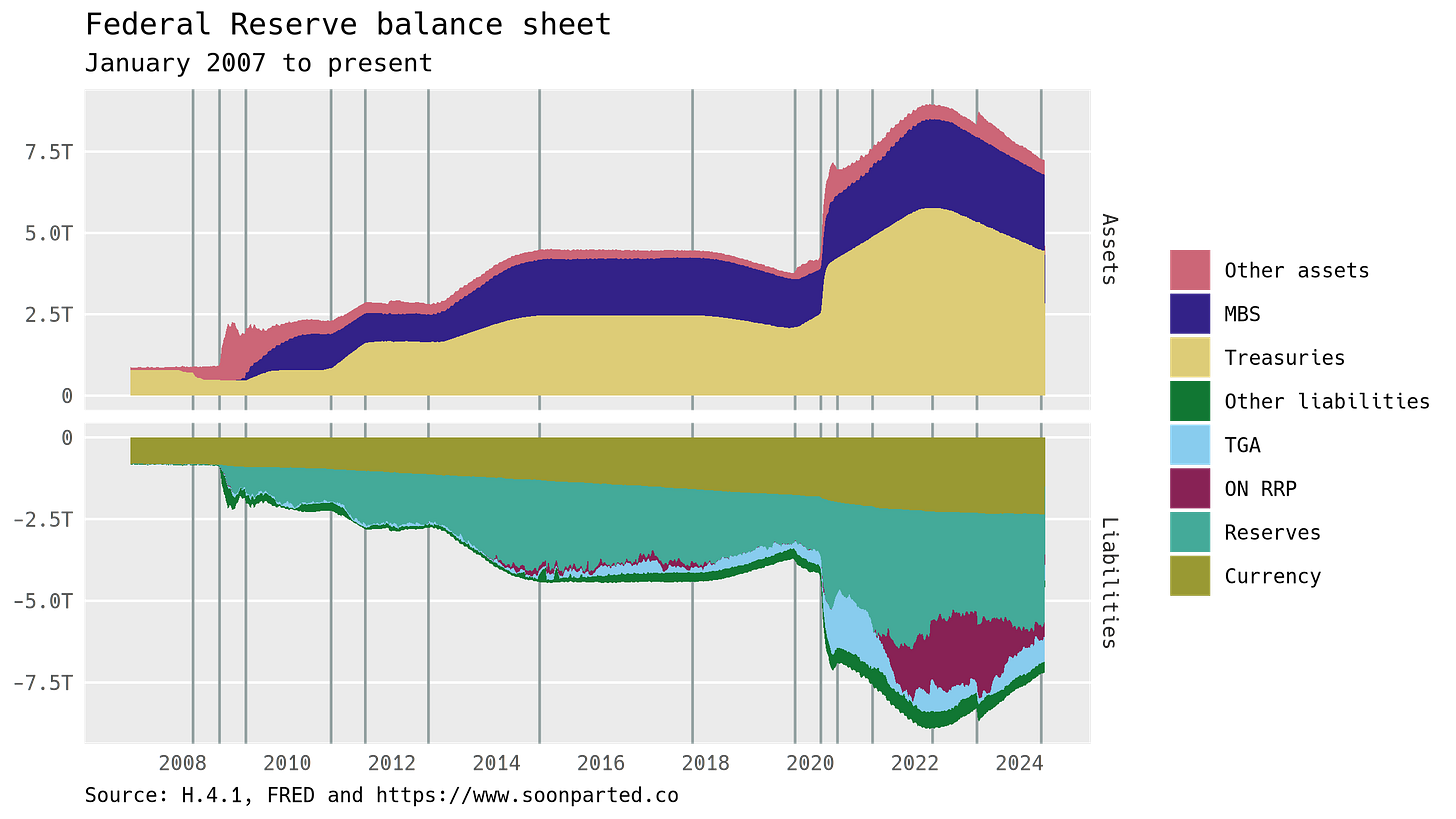

This graph shows the Fed’s balance sheet from before the 2008 crisis all the way to the present. Assets are above, liabilities below. Vertical lines mark the important turning points in the central bank’s balance-sheet policy:

The repo panic was brought on by the Fed’s post-2008 contraction, which as the graph shows was forced into reverse. At the same time as the Fed was allowing its Treasury holdings to decline, the Treasury itself was issuing heavily, absorbing cash balances from other market participants. By late 2019, little cash was available for repo lending, and on September 17, intraday rates hit 10%, far above the Fed’s 2.25% upper limit for overnight money rates at the time, and far beyond the usual fluctuations in overnight markets.

The balance sheet expansion that followed seems modest in comparison to what was to come in 2020 and 2021, but it was a big deal at the time. The repo crunch had called into question the assumption that Treasury and repo markets are reliably liquid. One important consequence was the creation of the standing repo facility, which is designed to keep repo rates from spiking again. The SRF has yet to be activated, since pressure on rates has been downward not upward, but it seems likely to prevent a direct repeat of the 2019 crunch.

But other vulnerabilities have grown. In particular, hedge funds have continued to extend their short positions in Treasury futures, to nearly $1 trillion in notional open interest. The so-called basis trade involves pairing these futures positions with long positions in the cash Treasury market, funded with repo. Rising repo rates make the basis trade more costly, and if it were to be unwound in a disorderly way, it could certainly have wider repercussions for financial stability.