Subsidiarity

Political economy of finance, note #5

This post began as part of part of a series of notes (which begins here) for a two-week intensive course on the political economy of finance that I taught at Al Akhawayn University in Ifrane, Morocco. As it grew, however, the post exceeded the scope of that course. But Soon Parted readers can think of it as lecture #5. Here ends the series, for now.

In finance, hierarchy arises as a consequence of credit relationships and the obligation to settle them. Hierarchy means that at every level, some entities are closer to the top (or the center) than others, but how does that show up in the dynamics of the system?

One important manifestation of hierarchy is that there is a cost in moving from a lower to a higher level. Credit is available for the asking, by and large, but if borrowers face no discouragement from doing so, then the higher layers of the hierarchy will always be tied up responding to lower levels, and hierarchy would cease to mean much. So the mechanics of settlement impose a price for ascending the hierarchy; those at the lower levels avoid paying that price if they can.

Subsidiarity is the best name I can find for the principle that difficulties should be resolved at the lowest possible level in a hierarchy. I have not been able to find any examples of the word being used in a monetary context, but as far as I can tell it is a good fit. Below, an example of how hierarchical payment mechanics induce subsidiarity, by steering market participants to resolve their debts as efficiently as possible.

The Fed’s standing facilities

The example uses entirely real features of the dollar payment system, and combines them in a not-very-realistic situation to illustrate the point. Focus on the Fed, center and steward of the dollar payment system. The Fed now offers standing facilities, mechanisms by which money market participants can borrow needed funds, or deposit excess funds. The facilities are always available, and within certain limits their availability is guaranteed, hence “standing.”

The lending facility (SRF) exists to make sure that normal payments usually succeed. If a bank needs to complete a payment but is short of funds, they can borrow, at interest. The deposit facility (ON RRP) exists to create a floor under interest rates, so that the central bank can be sure that money is not being lent more cheaply than it wants. The facilities use the repo market, meaning that the exchange of funds is matched by an exchange of collateral in the other direction.

Suppose then that a payment is due between two entities, a borrower Left and a lender Right, each of which has access to the Federal Reserve’s repo facilities. To make it a limiting case, suppose also that neither side makes recourse to private money markets. This second assumption is decidedly counterfactual, which is precisely the point, as we shall see.

The T accounts below illustrate the settlement mechanics in such a situation. The first line shows the debt outstanding, and because Left will use repo borrowing, we suppose that it holds sufficient collateral (1). To gain access to central bank reserves, that is to the medium of settlement, Left can go to the Fed and borrow using a repo transaction at the standing repo facility (SRF). Row (2) shows the flows of money, and row (3) shows the flows of collateral. The posting of collateral is indeed a credit relationship, but is not normally shown on balance sheets as published. I show it here to bring out the mechanics more clearly. As we see, Left posts collateral and expects to receive it back:

With these reserves in hand, Left can use them to complete payment (4). But now Right has more reserves, and we are assuming that it does not want to place them in private money markets. It can instead deposit the funds in the Fed’s overnight reverse repo facility (ON RRP), a repo deposit account. Line (5) shows the money side, and line (6) shows the collateral side.

At the end of the transaction, the Fed has opened two repo transactions, one on each side (7). Collateral has moved in the opposite direction (8).

An outside spread for repo markets

So much for the balance-sheet flows for this transaction, but what about interest? The repo borrower, Left, must pay the SRF rate, which the Fed sets equal to the top of the target range for the federal funds rate, currently 4.5%. The repo depositor, Right, receives the ON RRP rate of 4.3%, which the Fed sets 5bp above the bottom of the target range for the fed funds rate (currently 4.25%). The Fed therefore earns a spread of 0.2% or 20 basis points.

That 20 basis point spread is the Fed’s compensation for providing repo intermediation to ensure that the payment can be completed. It is a high price for Left and Right to pay, as money markets are responsive to spreads of even 5 bp. Twenty is huge, and as such is a strong incentive for Left and Right to find a cheaper alternative.

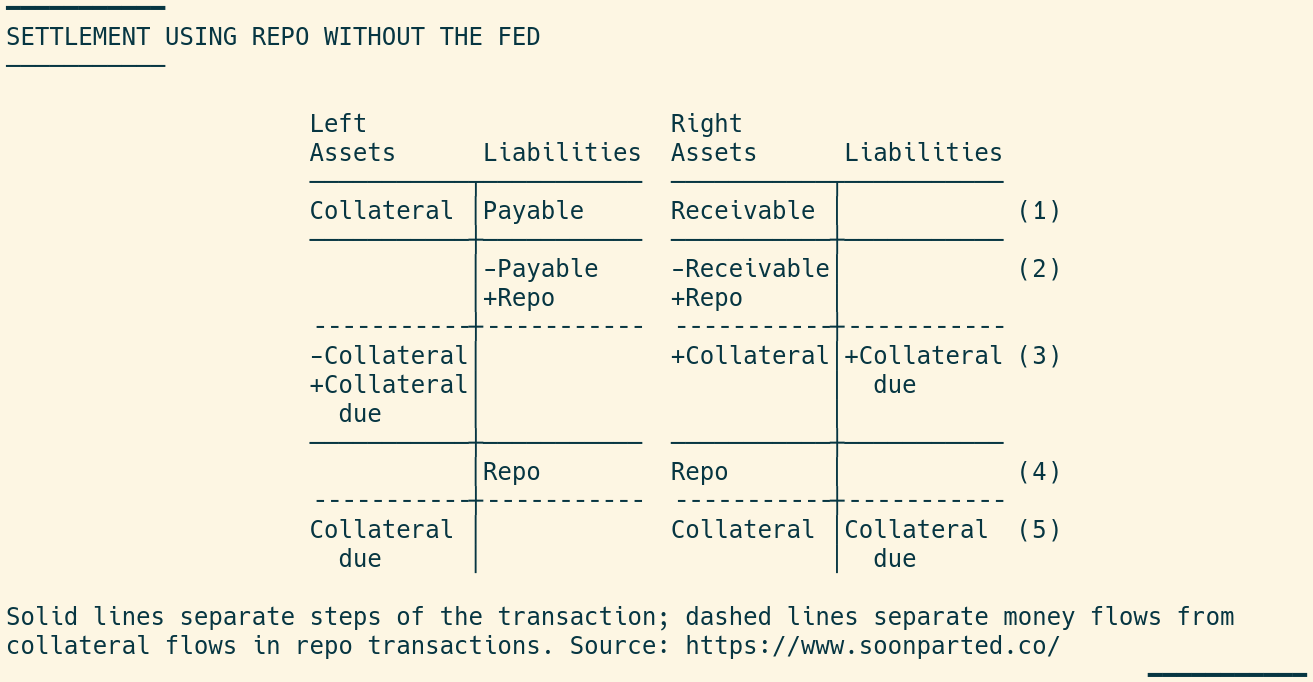

When money markets are functioning, as they normally are, there are indeed cheaper ways. To make the point as clear as possible, suppose that Left and Right don’t bother with the Fed at all, but instead simply do the repo trade between themselves. These T accounts achieve the same end result as above using a single transaction rather than using the Fed as intermediary:

As long as Right is willing to hold a claim on Left, this bilateral transaction achieves the same result as above. Right can earn ten basis points more, and Left can pay ten basis points less, or they can split the 20 basis points some other way, and still both sides will be no worse off than before, and at least one side will be better off.

The outside spread pushes mismatches down the hierarchy

These examples, admittedly, are still simplifications. They include some aspects of the repo markets but omit others. Still, the basic point is simple, correct and very useful for understanding hierarchy. The Fed’s facilities are open, but costly, and that cost gives others a reason to solve the problem on their own.

Political Economy of Finance

Subsidiarity (this post)