Proof of something

The coming Merge

Sometime soon, the Ethereum blockchain will shift from proof-of-work to proof-of-stake consensus. This change in financial practice will be effected through what might be the boldest software upgrade ever attempted—the Merge. The Ethereum community thinks of it as replacing a jet engine in mid-flight; Soon Parted might add that the jet is being steered by 200,000 individual pilots whose main existential commitment is to not trust one another. Also, by the way, the jet is carrying hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of cargo which could be destroyed if anything should go wrong. This is, in short, a spectacle worth watching.

Consensus is both a cryptographic and a financial phenomenon. In this post, while we wait for the Merge, I will try to add to the discussion of consensus by seeing it from the financial perspective.

Financial structure of consensus

Economically, a transaction (crypto- or otherwise) is final when all sides of the contract have been fulfilled. Before a transaction is final, one party could still choose not to hold up its end, stopping the transaction unilaterally; after it is final, a transaction can only be reversed by mutual agreement.

Consensus is the path to finality for distributed ledgers: a transaction is final when it is permanently recorded in all copies of the ledger. Validators in this system are the maintainers of consensus, a service for which, under the current structure, they expect to be compensated.

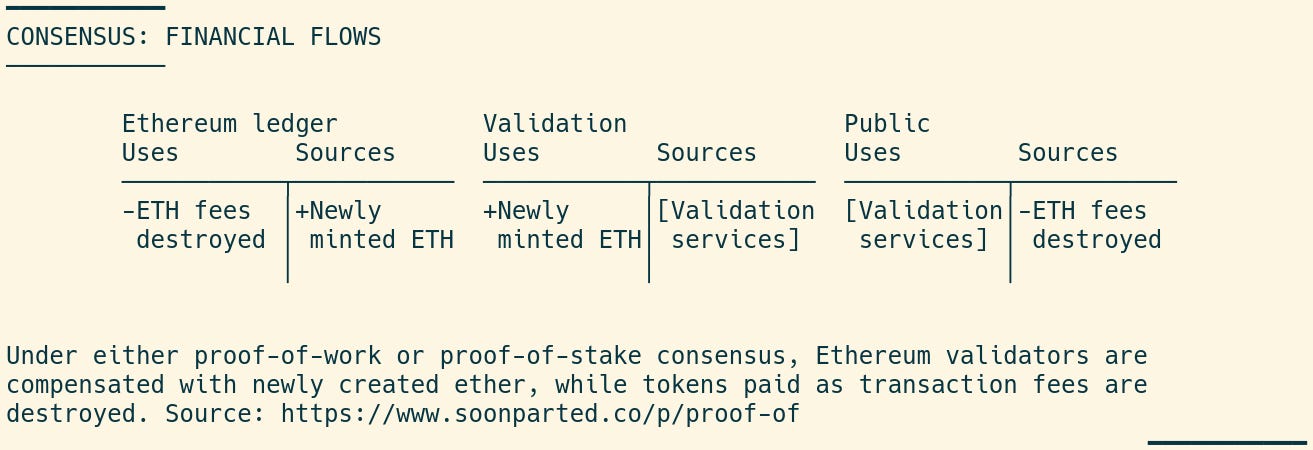

The T accounts below show my illustration of the basic financial flows associated with consensus, taking the Ethereum ledger as example. They use flow accounting, with uses of funds to the left, and sources to the right of each T account. The public uses validation services, a non-monetary flow, which are paid for in the form of transaction fees. Since last year’s London upgrade, these fees, paid in ether tokens, are destroyed. Validators, meanwhile, who provide the service, are compensated using newly created ether tokens:

The amount of newly created ether need not be equal to the amount destroyed in transaction fees. This breaks double-entry accounting, but so far it hasn’t broken Ethereum: ETH tokens, like bitcoin tokens, are one-sided instruments. That’s a story for another day.

Racing vs. taking turns

This kind of simplified accounting applies to both consensus mechanisms. The difference is in who gets to serve as a validator. In proof-of-work, validators act as “miners,” who race to complete a math problem that is hard to solve, but easy to check once a solution is found. The winner of this race shouts out the answer so everyone can hear it, proving that they won. They get the validation payment, and the race begins again for the next block. On average, a miner with up-to-date equipment can be sure of winning enough races to receive a steady stream of payments.

Miners are profitable when the value of their compensation in ETH is greater than their operating expenses, of which electricity is a big part. One of the key critiques of proof-of-work consensus is that this is a poor use of electricity, since the proof-of-work race doesn’t produce anything useful—it’s just a way to choose a winner.

Proof-of-stake, by contrast, is based on taking turns. Prospective validators must make a deposit of at least 32 ETH (worth about $50,000 today) into a programmable contract. The funds are held in escrow, and can be confiscated if the validator tries to cheat or lie. Once their funds are in escrow, validators take turns at the front of the line, and can expect on average to take in a share of the total validation payment, in proportion to the size of their escrow deposit.

Or maybe it will be dissensus

So what should we make of the Merge?

As a financial phenomenon, we might think of consensus as the version of the clearing and settlement process suited to distributed ledgers: the completion of each block of transactions means that those transactions are recognized by all, and so are final. Changing Ethereum’s consensus mechanism might be compared to other changes to financial infrastructure: decimalization, the sunsetting of LIBOR as the basis for interest-rate derivative contracts, or the introduction of central clearing counterparties. The Merge will deserve a place somewhere in that list, I would argue, if it is successful.