Twice is coincidence

Tricolor and First Brands

September brought a pair of interesting financial failures. At the surface the two cases are very different—Tricolor Holdings, a Texas-based auto dealer and subprime auto lender, filed for bankruptcy protection on September 10 after its creditor Fifth Third wrote down most of a $200 million loan. First Brands Group, an Ohio-based car parts producer, filed on September 28 following a precipitous fall in the market value of its debt.

Besides the connection to the auto industry, the two collapses have little in common. Tricolor integrated auto sales, collections and collateral management to support profitable issuance of commercial paper backed by its auto loans; First Brands issued debt to finance acquisitions while optimizing cash flow with extensive supply-chain financing.

Stability in the financial system doesn’t necessarily mean that bankruptcy never happens—it means that failures should not be transmitted upward in the financial hierarchy. Either of these bankruptcies, Tricolor or First Brands, could have passed without prompting wider concern about stability. In the event, however, the two have come simultaneously, which is enough to make credit markets jumpy.

Tricolor Holdings

Tricolor Holdings offered a modern, integrated take on the subprime auto lending market. Targeting borrowers with cash incomes and limited credit history, the company is best understood as a retail loan originator with an integrated collateral-management business. Tricolor’s loan terms typically demanded down payments of 11% and interest rates of 17%, based on a biweekly payment schedule.

The company paired these loans with collateral repossession practices that allowed it to make the most of the steep upfront payments: after default, vehicles could be quickly brought back to the dealership, cleaned up and put up for sale again. Each time the car is sold, the company pockets 11% of its value, paid in cash up front. As long as there are enough borrowers, it is better for Tricolor if they default than if they pay.

This business model allowed Tricolor to issue $1.4 billion in auto loan securitizations. Lenders and bond holders include Fifth Third, JPMorgan, Barclays, part of the Massachusetts state pension fund, community bank Triumph Financial, bond holders Charles Schwab, Pimco, and Capital Group. The company ran into trouble in recent weeks, due at least in part to high levels of defaults driven by the deportations of its borrowers. To cover the cash flow, it seems that Tricolor may have started double-counting collateral. Creditors got wind and opened an inquiry in August, and the company declared bankruptcy two weeks later.

First Brands

This week, auto parts maker First Brands Group also filed for Chapter 11 protection. The company grew rapidly over the last few years in a debt-funded expansion. It seems to have gotten into trouble with its trade financing practices, recorded in so-called off-balance-sheet instruments. Just because First Brands kept the arrangements off the books, of course, doesn’t mean that we have to do the same.

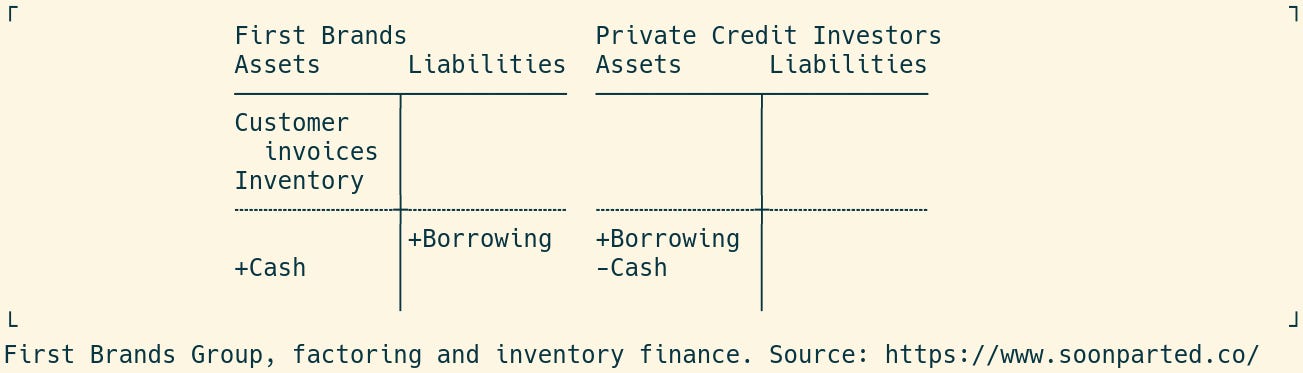

FBG borrowed against its own invoices, as shown in the balance sheets below. Having sold its product, the company could pledge its unpaid invoices, as well as its inventory, to investors for cash. When the proceeds of the sale are eventually collected, the funds can be used to pay the loans, with a premium to the lender for supplying liquidity. This is a standard commercial credit arrangement (called factoring when secured by invoices, but equivalent to any other kind of secured lending). It is normally a simple way to bridge the gap between delivery and receipt of payment:

At the same time, FBG borrowed to cover its own purchase of inputs. These reverse factoring arrangements achieve a similar effect (smoothing over payment delays) as invoice financing, but are initiated by the buyer instead of the seller:

When it failed this week, First Brands seems to have had as much as $10 billion in debt and off-balance sheet financing outstanding. The company’s creditors include the investment bank Jefferies and UBS’s O’Connor hedge fund. Some eagle-eyed investors raised concerns over an August refinancing deal, and the added scrutiny quickly revealed a significant cash shortfall.

It’s the sudden stop at the end

Both Tricolor and First Brands came apart in a matter of weeks. Whatever the underlying problems, it is always illiquidity that brings on such a rapid end. Both of these companies met their end when they finally ran out of cash.

The differences in circumstances are therefore either deeply reassuring or deeply worrying, depending on your interpretation. Perhaps the two failures are unrelated, simply a bad roll of the dice in the business-as-usual flow of creative destruction. Then a few lenders will get burned, lessons will be learned, or maybe not, but either way it doesn’t mean much about what comes next. Alternatively, the synchronous failure of two unrelated companies could be a sign of trouble at a deeper level. If they indicate tighter money, a general flight towards cash, then there may be more turbulent financial conditions to come.