Variation margin

Financial plumbing in commodities markets

We are reckoning with a surge in commodity prices, due first to supply-chain bottlenecks arising from the global stop-start at the beginning of COVID-19, and now to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the attendant production, logistical and financial constrictions that have arisen or been imposed in response. The consequences are only beginning to take shape.

Short-term funding troubles prompted a European group of energy traders to ask the ECB for help last month, though their plea was rejected.

These liquidity difficulties are somewhat surprising. At the macro scale, commodities are in a one-way flow from extraction or agriculture, into a production process, and on to final consumption. Commodity traders are gatekeepers along that flow, and so one might think that supply shortages would be good news for them. Indeed this has broadly been the case, with Vitol, Mercuria, Trafigura and Glencore all posting eye-popping profits.

The question has turned out to be bigger than I thought. In this post, I get started on the issue by illustrating the mechanics of margin flows in commodity futures contracts, which helps show why the sector is both recording bumper profits and facing a liquidity crisis.

Commodities futures contracts

Global commodities prices are mostly traded in futures markets, for example the London Metal Exchange for industrial and precious metals. Any futures contract connects a seller, the short side of the contract, with a buyer, the long. When the contract is created, the two counterparties fix the price and the delivery date, days or weeks in the future.

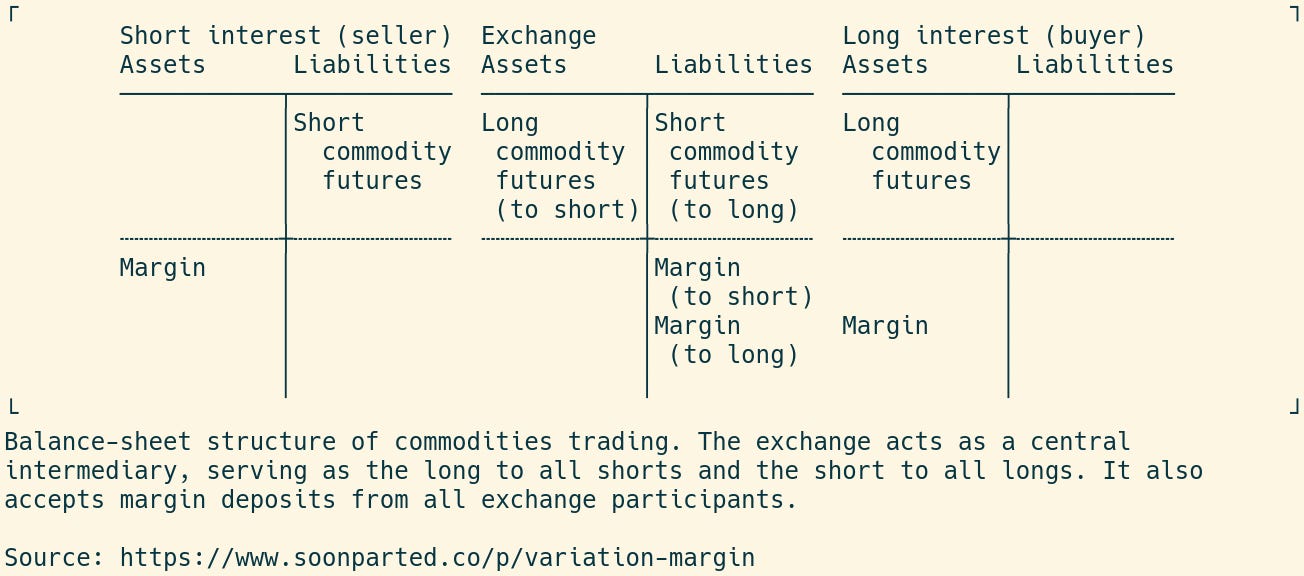

The exchange itself serves several functions. First, it organizes trading around standardized contract terms and delivery dates, which facilitates the ongoing process of compromise between buyers and sellers. Second, the exchange acts as an intermediary, playing short to the longs and long to the shorts, who are thus protected from each other. And third, the exchange accepts and maintains deposits of variation margin from each participant in the exchange. These T accounts illustrate the balance-sheet structure of commodities futures contracts between the time they are created and the delivery date:

Margin payments

After the futures contract is open, the spot price of the underlying commodity (nickel, for example) continues to fluctuate. This means that although the delivery price of the futures contract is fixed, its value continues to change. Specifically, in the current context, commodities prices are rising, so short futures positions—agreements to sell at a price already set—are becoming less valuable. Those who have placed losing bets might be tempted to walk away from their contracts.

To manage this risk, the exchange requires participants to maintain margin deposits. Though the rules for this can be complex, the principle is simple: each day, the losing side must cover its losses by posting additional margin; the winning side receives a cash payment into its margin account, which it is free to withdraw.

The T accounts below use sources and uses accounting to illustrate these flows. (The context is one of rising prices—swap “long” and “short” for falling prices.) First, the appreciation creates a capital loss for the short interest and a capital gain for the long. In accounting terms, these are expense and income flows respectively, balanced in both cases by an equal change in each entity’s booked valuation of the futures contract. The exchange records a capital gain on its long position and a capital loss on its short position, which by design nets out exactly:

So far, these are paper gains and losses only. But margin requirements force participants to realize them as cash flows: when the price rises, the short interest must put up additional margin, while the long interest may take down its margin balance, bringing it into cash. The exchange just has to move funds from one account to another, so the only question is whether the shorts can make their margin payments.

This of course is the sticking point. Commodity traders would normally draw on bank credit lines to fund margin calls. But if I understand Zoltan Pozsar correctly, these credit lines are close to exhausted, because traders have had to finance idle inventories stuck on ships waiting to come to port. This explains the puzzle of why commodity traders should be struggling despite their profitability: they are making lots of money on high prices, but their cash is tied up in unusually large inventories, leaving them vulnerable to margin calls.

Echoes of 2008?

Some observers have been reminded of the 2008 crisis, another moment when sudden price movements froze the short-term financing channels on which market-making depends. Both Steven Kelly, writing for Bloomberg, and Karen Petrou, writing in the Financial Times, have made the case that central banks should prepare to backstop commodity traders.

They could be right. Maybe the commodity surge is the new mortgage bust. Maybe “it” could happen again. I suggest we get clear on the mechanics, just in case. But I suspect that buying when everyone wants to sell, as in 2008, is not quite the same thing as selling when everyone wants to buy. More to come on this.