Runoff

The Fed's balance sheet over the last half-cycle

It is increasingly certain that the Fed will begin to contract its balance sheet beginning after its next meeting on May 3 and 4. The minutes of the FOMC's March 2022 meeting propose a pace of contraction of about $95 billion per month. Mechanically, the central bank's open market desk will achieve the contraction by declining to reinvest the proceeds of maturing securities, hence "runoff."

This will mark a turning point in the course of monetary policy, making history of the entire half-cycle of balance-sheet expansion. This post creates a map of that expansion, to serve as a reference point as we make sense of the coming contraction.

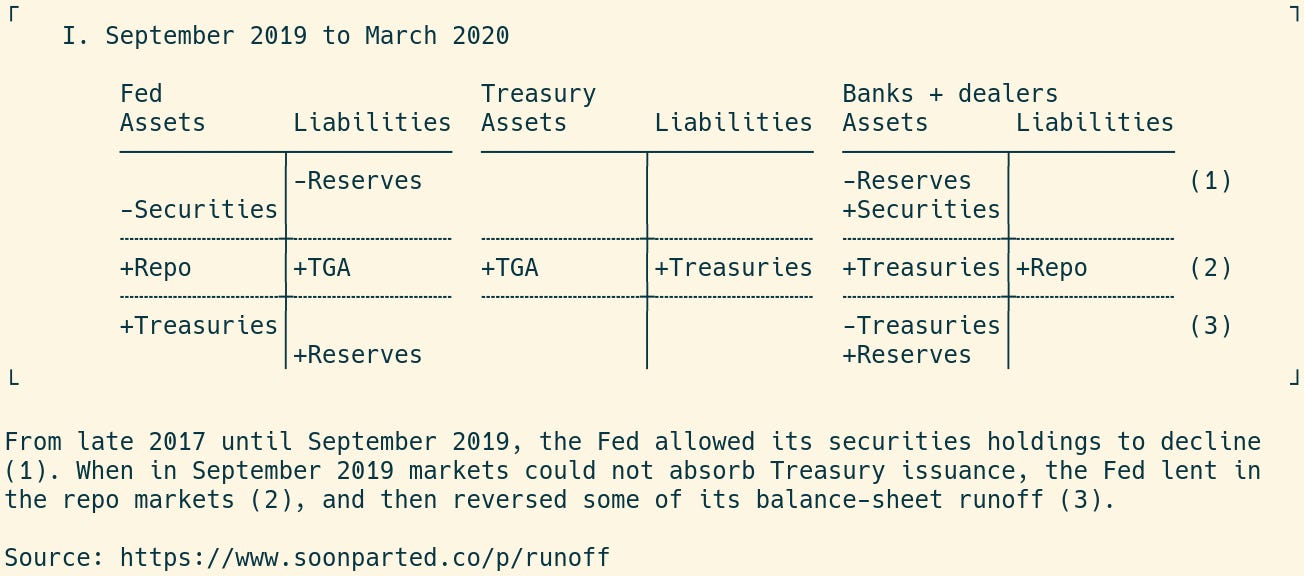

The September 2019 repo crisis

We should begin not in March 2020 but with the repo crunch of September 2019. The spike in repo rates of that month was a side-effect of the Fed's last phase of balance-sheet contraction.

The emergence of COVID-19 six months later would draw attention away from the issues in Treasury and repo markets, not without justification. Now, though, as the central bank's stance changes back to contraction, the repo crunch is again on policymakers' minds. Specifically, the events of September 2019 led to the creation (in June 2021) of the Fed's standing repo facility as an automatic backstop to prevent repo rates from rising too high. The SRF is now a key component of the balance-sheet runoff strategy.

Emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic

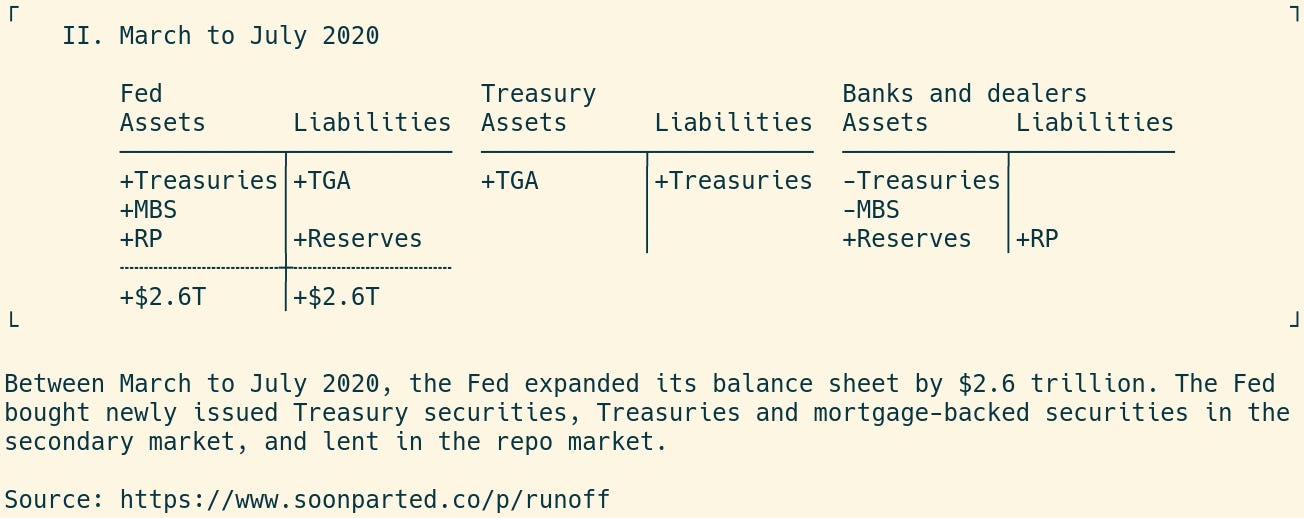

When COVID-19 emerged as a global pandemic in early 2020, the Fed responded rapidly, expanding its balance sheet by $2.6 trillion over the course of about four months. I interpret this in two ways.

During the confusing and disequilibrating early days of COVID-19, the Fed pulled out its playbook from the 2008 crisis. This was justified, the FOMC believed, by the rapid deterioration of the economic outlook, combined with the evaporation of liquidity in key funding markets.

One could also frame this as a question of war finance—the public health emergency would certainly require major public expenditure, and so heavy borrowing by the US Treasury. To ensure that this could be brought off successfully, the central bank guaranteed the government's ability to borrow, by buying the debt itself.

Asset purchases were funded with an expansion of the Treasury General Account (TGA)—the US government's transaction account—and by the reserves of the commercial banks. The T accounts show an outline of the transactions.

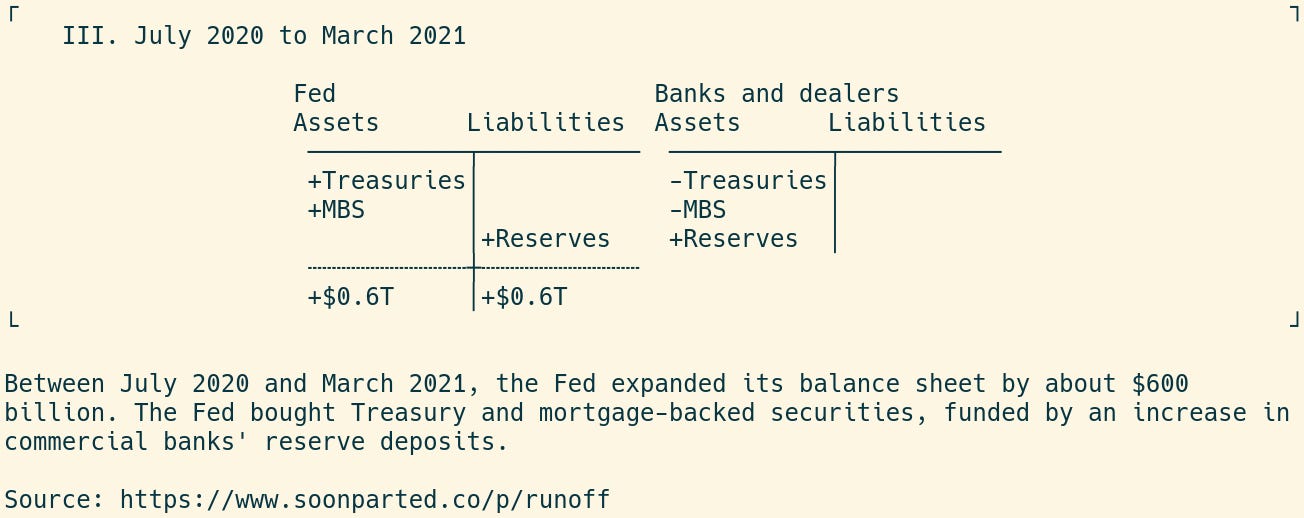

Pandemic steady state

By July 2020, a kind of steady state had set in. In public health terms, it was becoming clearer how to manage the virus, even if this was not universally achieved in practice. In financial terms, the Fed stabilized by March 2021 on a path of asset purchases of $120 billion a month, two-thirds Treasuries and one-third mortgage-backed securities. This was funded by an expansion of the reserve deposits of the commercial banks. The TGA balance did not come down, instead remaining elevated during this period. The transactions are summarized here:

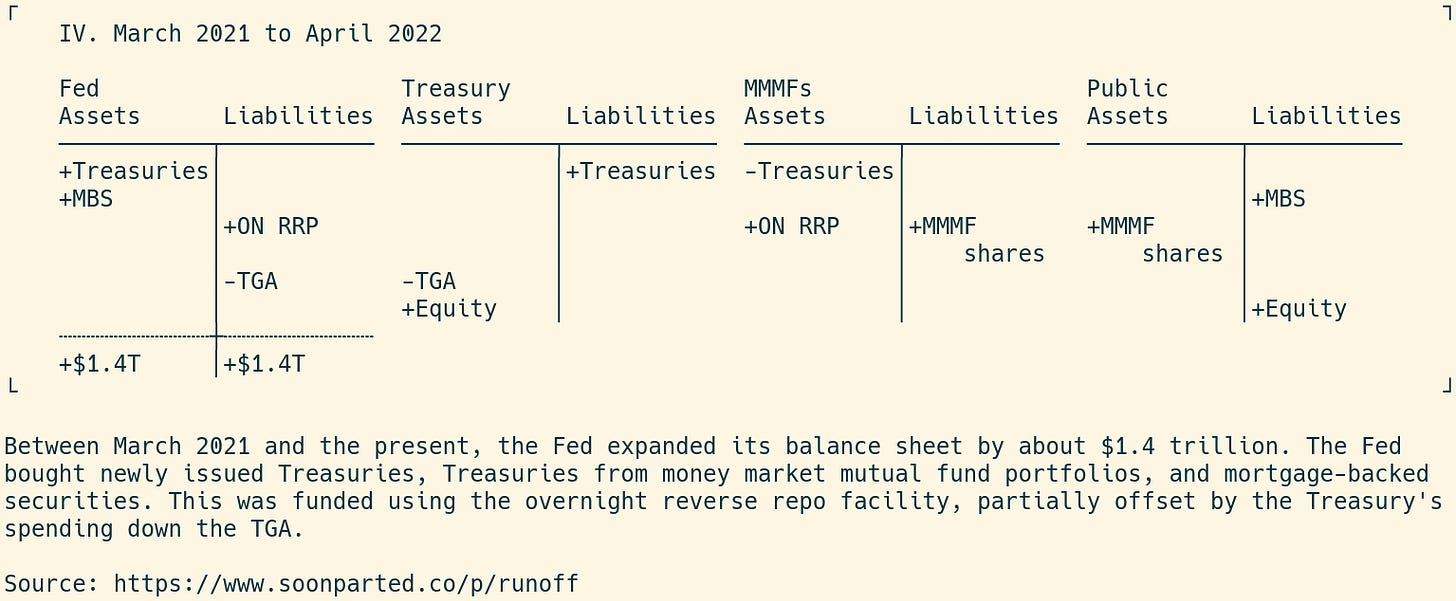

Overnight reverse repo facility

By March 2021, US commercial banks' balance sheets were increasingly constrained by the supplementary liquidity ratio. Rather than stop asset purchases, or change the rule to allow banks to hold more reserves, the Fed chose instead to accept deposits from money market mutual funds (money funds or MMMFs) through its overnight reverse repo facility. The ON RRP facility already existed, and had been used as an experimental backstop between 2013 and 2019. Beginning in 2021, however, balances in the facility grew to very high levels, where they remain today.

The result was that the Fed could continue asset purchases, funded now by expansion of money funds' repo deposits in place of commercial banks' reserve deposits. Money funds, for their part, sold Treasuries and issued more shares. Meanwhile the Treasury continued to issue debt while spending down its deposits in the TGA. (I show the Treasury as acquiring a residual or equity claim on the public, on which it can collect by taxing.) Schematically:

Runoff is set to begin in May 2022

The Fed's balance-sheet expansion was "tapered" off, beginning in late 2021. Since then, US consumer price inflation has reached four-decade highs, while Russia's invasion of Ukraine has generated fresh inflationary pressures through supply chains and commodities. The Fed meets next in the first week of May, and every indication is that balance-sheet runoff will begin promptly thereafter. It seems impossible to say what what happens after that, but let's at least try to remember how we got here.

Thanks Daniel for the clear exposition of balance sheet mechanics. I am worried the Fed is too sanguine about how the RRP will operate under balance sheet reduction. Just because it ran up to $1.7 trillion so easily doesn't mean it will be the first part of the balance sheet to shrink in QT. For instance, money-market funds need incentive to switch out of the flexible RRP into market securities (for instance T-Bills), yet the return on T-Bills is virtually identical to the expected return on RRP reflected in the Fed Fund futures strip. Will the Fed need to introduce a penalty rate on RRP?

This could be important for wider financial stability issues because if RRP fails to decline as expected on balance sheet run-off then bank reserves are required to fall with the possible impact on securities settlement and repo markets.

Hi Daniel, great piece. Why the introduction of equity in the most recent diagram? Thanks